The Island, 1951 Oil on canvas © the artist's estate. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

I discovered the work of Elinor Bellingham - Smith through a chance encounter. I was in Ipswich (I can’t for the life of me now remember what I was doing there) , but I do remember very clearly the first time I saw her work. I had idly wandered into the Christchurch Mansion where an exhibition called “A Female Focus” was showing. Included amongst the work of Suffolk women artists were three oil paintings that held me breathless with excitement. They were landscapes that spoke to me of December walks, where the fields are bleached of colour and only the bare bones of spent seedheads and skeletal trees remain.

The landscape of East Anglia has been captured endlessly, in particular by male artists, but this was an East Anglia I recognised and loved: a place of quiet subtlety, where colours are smudged by the damp and drizzle. Her paintings depict a sense of the place, in the manner of the ghost stories of M.R James. Her strange figures, often children, look out over fences, or glance over their shoulder, as though we have suddenly interrupted their private games. There is a sense of innocence, but also of unease.

River Scene with Figures, 1952 71cm x 91cm oil on canvas© the artist's estate. Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums

They are poetic, dreamlike works and I wondered about the woman who could convey such “enjoyable melancholy.”1 The image I conjured of her was of a reserved and reclusive figure, living a life of gentility in a remote farmhouse, but what I discovered couldn’t have been further away from my assumption.

Elinor Bellingham - Smith was born in 1906 into an affluent, artistic family. Her father, a distinguished surgeon and Registrar at Guy’s Hospital, was also a keen art collector who no doubt influenced her final choice of career. Her first choice had been that of a dancer, she even appeared in a London chorus line, but she also studied piano at the Royal College of Music, winning several prizes and was certainly good enough to consider life as a concert pianist. It strikes me that these disparate inclinations perfectly reflects the contradictory nature that emerges. But this trajectory was halted by a back injury and instead she decided, quite suddenly, to be an artist. Her mother was appalled at this volte-face, declaring that at the Slade she would be joining those who were “ good for nothings, unkempt, smelly and certainly all lack [ing] in resolution”.

Fortunately her father took a different view. He encouraged his daughter to produce drawings for the exacting professor Henry Tonks, and following a terrifying interview, that she likened to being in a “dentist’s chair”, she was accepted and embarked on her first term in October, 1928.

Some three years older than the rest of the intake, Elinor was an ambitious and determined painter, keen to join the “right set” and was by “no means a shy weed”.2 Exuberant and fun, she would “turn a cartwheel on the Slade lawn” at the drop of a hat. Her determination extended to her choice of partner too. She met the dashing and popular Rodrigo Moynihan and, according to her friend Nicolette Devas, “Elinor made her choice among the men, picked the one she wanted and to my awe it was not long before she made her conquest”.

Already pregnant with her first son, John, they married in 1931, borrowing a ring from her friend Nancy Sharp and so began the tempestous, “corrosive union3” that marked the next thirty years.

It seems that she was left holding the baby, while endeavouring to sustain her career, from almost the beginning of their marriage. Moynihan would disappear for days at a time, returning with no explanation, making it necessary for Elinor to rely on fashion illustrations for Harper’s Bazaar for an income. Financial relief finally came from Jack Beddington, of Shell, who commissioned several artists, of whom Elinor was one, to create posters of the British landscape which led to further commissions.

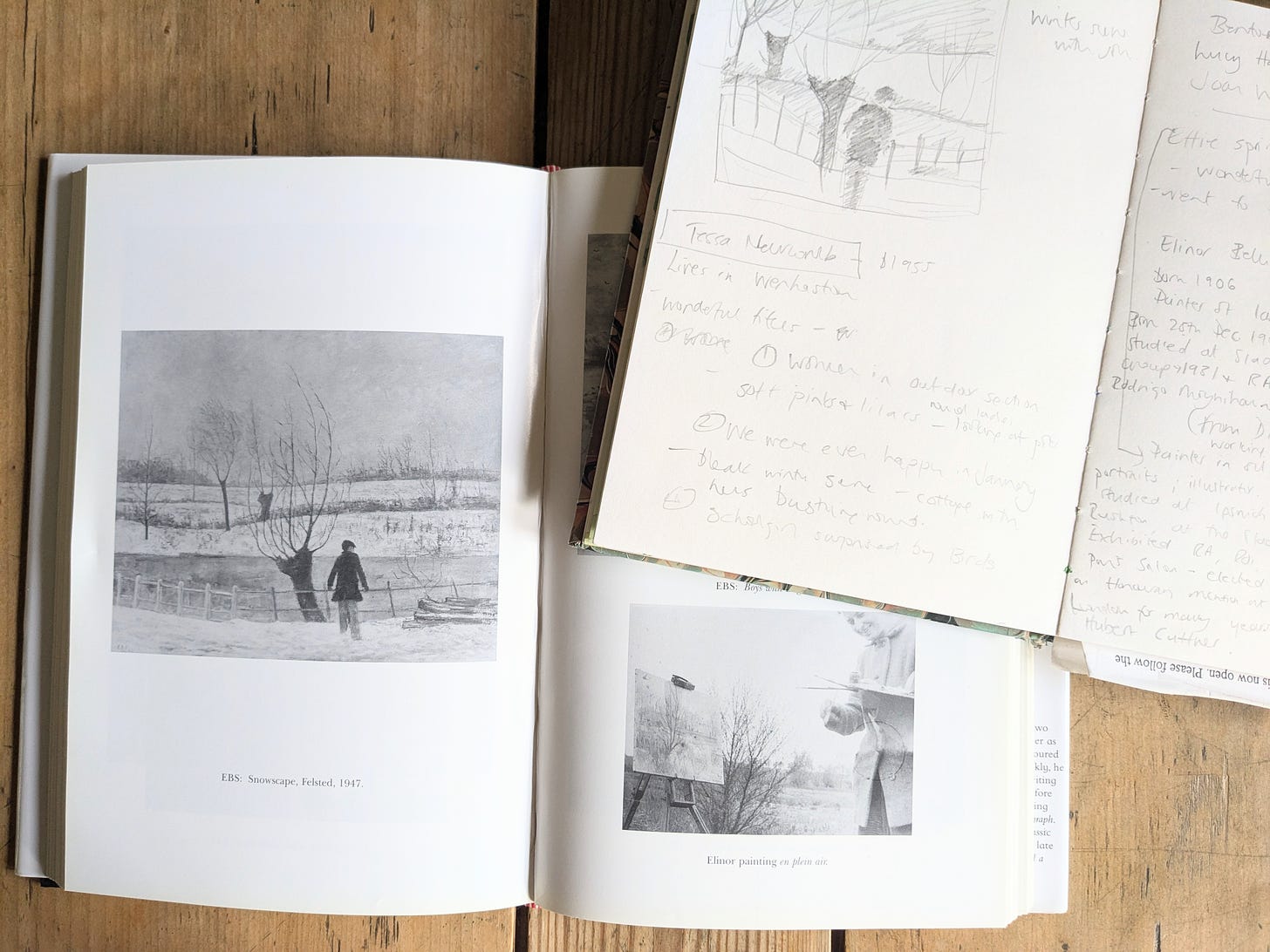

Illustrative work such as this became her focus until the outbreak of the Second World War, when such commissions declined. But this turn in fortune finally allowed Elinor to explore her own work, and she began to use oil on canvas for the first time. The couple were staying as part of an artists’ commune in Monksbury, in North Essex, and from the farmhouse window, she painted the savage winter of 1939 for three, solid months. Her son, John, often appears as a lone figure in the landscape and it was one of these paintings that had so attracted me in that exhibition. The other two I have been unable to trace, but they were all set in the winter chill.

One of the paintings from the Ipswich exhibition. It had then been entitled “Winter Scene with John,” but I finally discovered it as “Snowscape, Felsted, 1947”. Here is my sketch made on the day of my visit, 1999

Winter Afternoon, Oil on canvas, 1952 © the artist's estate. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

After the war, the family moved to Old Church St, just a few doors along from the Chelsea Arts Club. Their home became a salon for Rodrigo’s “all male gang” and riotous drinking parties became the norm. That most sober of painters, Sir Alfred Munnings, admired Elinor’s work and encouraged her to leave the social rowdiness of Chelsea to stay awhile in Essex, “to sit by a riverbank”. But she declined.

Orchard Snowscape, Felsted, 1944 14cm x 22cm © the artist's estate. Chelmsford Museums

Rodrigo became more famous, and affluent, painting the portrait of Princess Elizabeth, but Elinor continued to run the household, painting when she could, though constantly frustrated by the interruptions, declaring that “there was always something”4 that hindered her progress.

It is a wonder she painted anything, yet in 1948 she had her first of seven solo shows at the Leicester Galleries. It was a sellout and she declared the private view “magical”. She was finally emerging as a great painter in her own right, and not just “Rodrigo’s meal ticket” as some bitterly thought. The novelist Elizabeth Taylor had swept into the private view and thrillingly bought a painting. They were to become great friends, the writer frequently inviting her to stay, giving her valuable solitary painting time. Elinor said, “we suffered from the same self-doubt about our work and the horror of being exposed at private views and publishing parties”.5

In 1951 she won second prize at the Festival of Britain for “The Island”, a strange dreamlike painting at the head of this post. The critic David Sylvester wrote that she was:

one of those English landscape painters who paint the weather…an equivalent on canvas of her experience of being alone in a flat country under a great canopy of sky.6

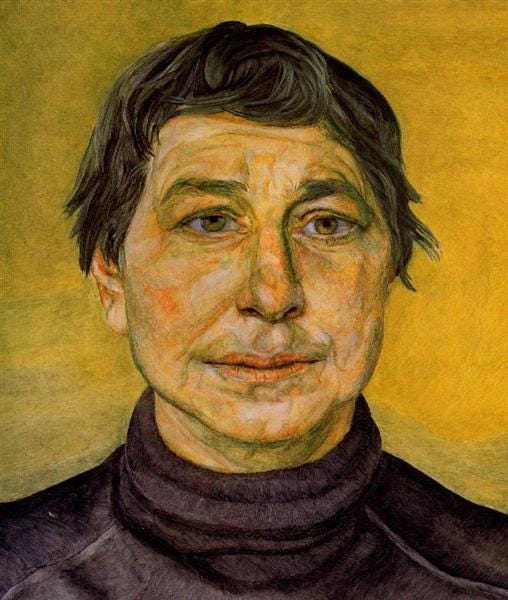

But the toll of living the bohemian life, their heavy drinking, Rodrigo’s encroaching jealousy roused by Elinor’s growing success, and his on-going affairs, led to their inevitable, painful separation. In the midst of this turmoil, Elinor inexplicably agreed to sit for Lucian Freud, a fellow member of the infamous Soho Colony Rooms. The portrait called, “A Woman Painter,” from 1954, is an unfliching view of her suffering and my most shocking discovery about her. She looks worn, lined and much older than her 48 years. Her hair is chopped and unkempt and the high collar seems to constrict her.

“A Woman Painter”, 1954, oil on canvas by Lucian Freud Copyright the artist’s estate

Colony Room 1 - Michael Andrews oil on board, 1962 Copyright Michael Andrews Estate / Tate Gallery

There is a sense of distance, of looking into an alien world, in this painting, with the unsettling figure of Lucian Freud (centre) staring directly at us. The painting was created at the time Elinor and Rodrigo were members.

After their divorce in 1960, she moved to Cox Farm in Boxford, Suffolk. The failure of her marriage had hit her hard and the move away from London followed her attempted suicide. Here she finally found a place of peace and retreat, but the darkness of those years left their scars. Her son remembers her remarking, “We went through the horrors then, didn’t we?”

It is hard to align the hard drinking frequenter of the Chelsea Arts Club, and the Colony Rooms, with those wistful, gentle landscapes. They seem so at variance. The paintings I saw, so many years ago, haunted me. I tried at the time to discover more about her, though there was little but the bare of bones of her biography to be found. The tale of their marriage by their son John gives scant insight into her painting methods, or indeed to her choice of subject, which is in such contrast to her tumultous life. Perhaps his sense of detachment is understandable as an only child caught up in the storm of their marriage. Does the biography affect how I now see the paintings? A little. I wish I could peer further into their mystery, but perhaps such things are best left unanswered.

I shall leave the final words to her friend Nicolette Devas :

The weather was the real subject. Her integrity and drive was such that she never condescended to the merely pretty and charming; the pitfalls of so many female artists. Though her paintings are pretty and charming from colour and subject matter, they are sustained by a muscle of austere, masculine organisation. As she has matured, the romantic element has dwindled, and now the wind, the rain, the frost control her canvases without rivals. 7

The Willow Tree oil on canvas 50.7 cm x 61cm (1930 - 1960?)

© the artist's estate. Harris Museum, Art Gallery & Library

Something to read

A Fugue in Time by Rumer Godden Why had I never heard of this book before? Following reading “An Episode of Sparrows” and “The Diddakoi”, I found this listed in my local library catalogue and ordered it on a whim. It is extraordinary. Initially I was disorientated by the shifts in time and character, but I soon adapted to this experimental approach . It tells the story of a house, over one hundred years, of three generations, slipping between them over the course of a single day. Thankfully, it was recently reissued by Virago, and is not to be missed.

The Great Gale by Hester Burton Another wonder from the County library archives. This tale of a fictitious Norfolk village is set during the great flood of 1953. Written for older children in 1960, it powerfully conveys the terrible destructive force of the storm that resulted in a 100 deaths in Norfolk alone. Beautifully illustrated by Joan Kiddell-Monroe, it is a fascinating and moving read of how a community rebuilt their lives.

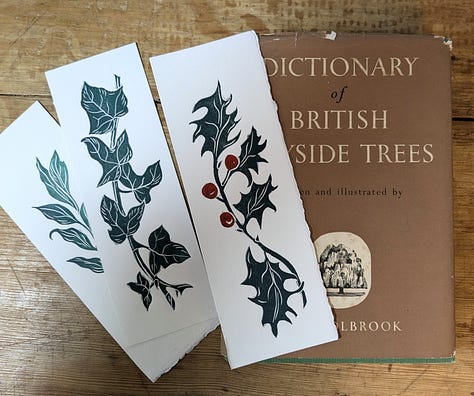

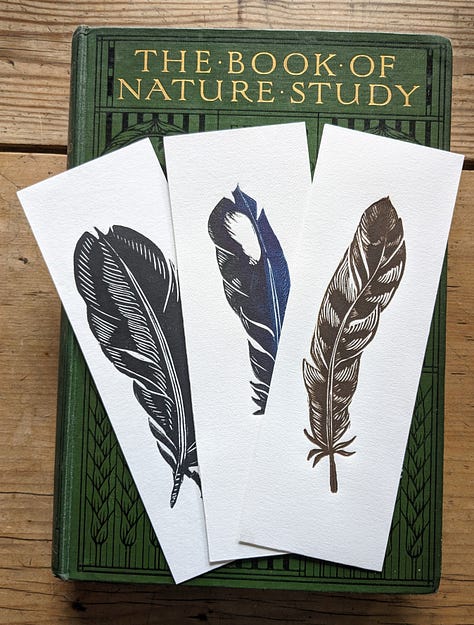

Something to slot into a book

After putting my handprinted, linocut book marks on Notes, several of you have asked when they can be bought, so here they are! I have a selection in my shop, on my website, so do pop along and have a look.

Thank you again for your company and for sharing your time with me here. I look forward to seeing you again in a couple of weeks and, if you enjoyed this piece, do please press the “Heart” to help my post to be seen. It makes all the difference and brings me great cheer! And, if you are a recent subscriber, or a regular visitor, do drop me a line in the comments, it is always lovely to hear from you!

Further reading

Two Flamboyant Fathers - Nicolette Devas , Women Artists - Alicia Foster

Restless Lives - the Bohemian LIfe of Rodrigo and Elinor Moynihan - John Moynihan

Voyaging Out - Carolyn Tarrant

M.H.Middleton

Nicolette Devas

John Moynihan

John Moynihan

John Moynihan

From, “Voyaging Out”, Carolyn Tarrant

Nicolette Devas.

Always nice to discover a 'new' artist. As we did recently via 'Fake or Fortune', which introduced us to Helen Mc Nicoll.

What an interesting artist. Those painting are wonderful - obscure in a way and rather eerie. Also interesting that you mentioned the Rumer Godden. I found it in a second-hand bookshop a while ago and it is in my reading pile. I am looking forward to reading it even more now.