The Way through the Woods

An unsettling fairy tale, drawing alone in the woods and fungi treasures

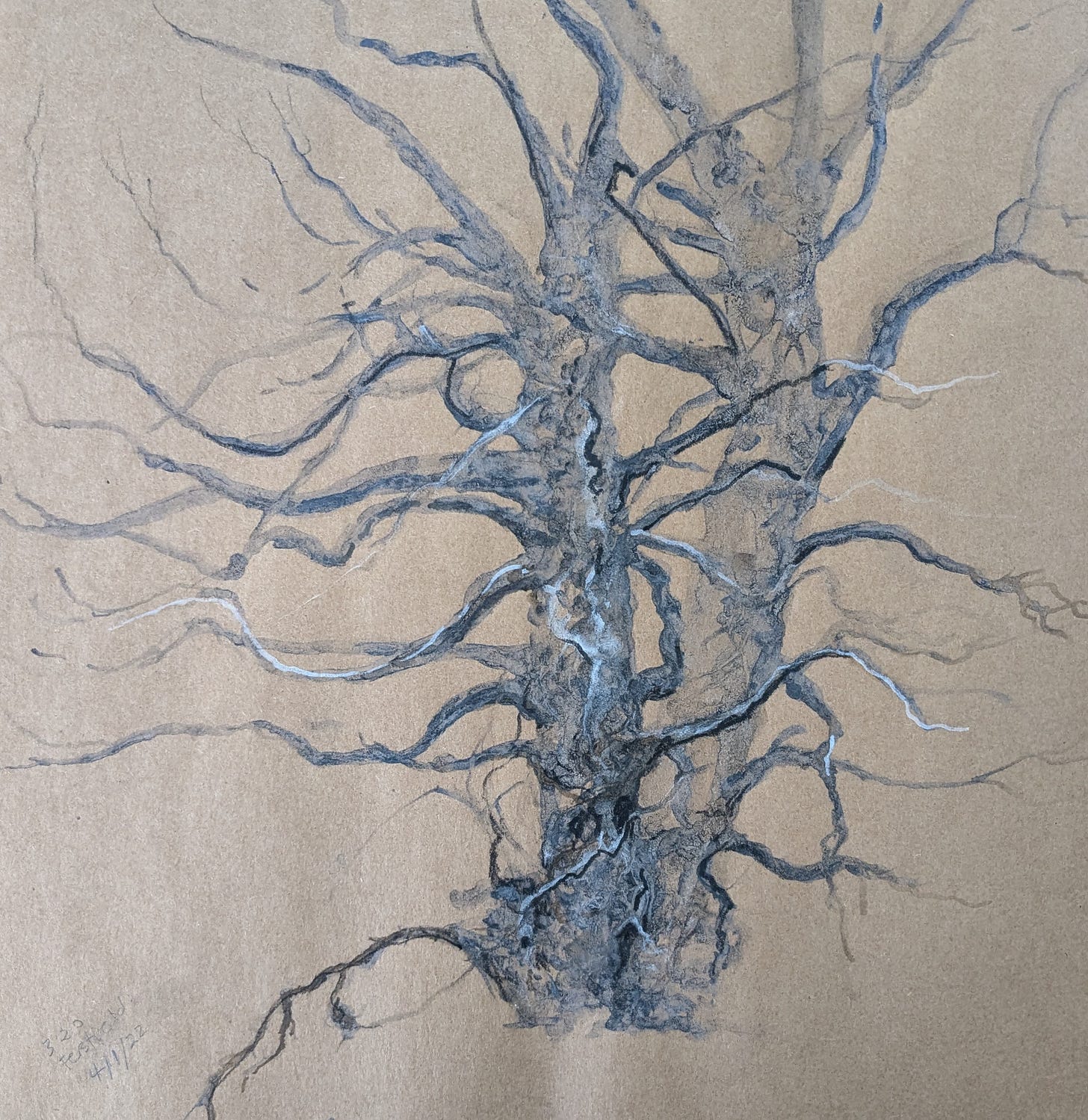

Wayland Wood as I began my walk

Recently, I've started to feel I'm losing my way when it comes to my art. It is as if I've wandered off the path and don't know how to find my way back.

I have started lots of new drawings and prints, but none of them are leading in a clear direction. I have pinned them up on my studio wall and I have sat and looked at them, just waiting for a spark to come. Such lulls are not uncommon. There are bursts of activity, when everything surges forward and suddenly, it stalls. Sometimes, it is best to forge ahead, at others it is better to wait.

Drawings and monoprints, works in progress on my studio “thinking” wall

It was during this waiting time that I decided to visit Wayland Wood. It had been recommended to me while chatting to another artist at an exhibition. When she asked what I painted, I found myself saying, “I love drawing trees…”

“Ah, then you must go to Wayland Wood.” I had vaguely heard of it, though had never visited. While I do paint other subjects, when I feel uncertain, it is to trees that I turn.

Wayland Wood is a thirty minute drive away, an ancient patch of woodland in the Norfolk Brecks. Owned by the Woodland Trust, it is flanked by the busy A1075, and the swift turning leads you to a tiny carpark, that is completely encircled by a dense canopy of trees. On the day I visited, there had been heavy rain all morning and the dark branches were dripping. There was not a soul to be seen or heard. The canopy dampened the traffic noise and, as I went beyond the barrior, it seemed a place where the intrusion of modern life no longer existed.

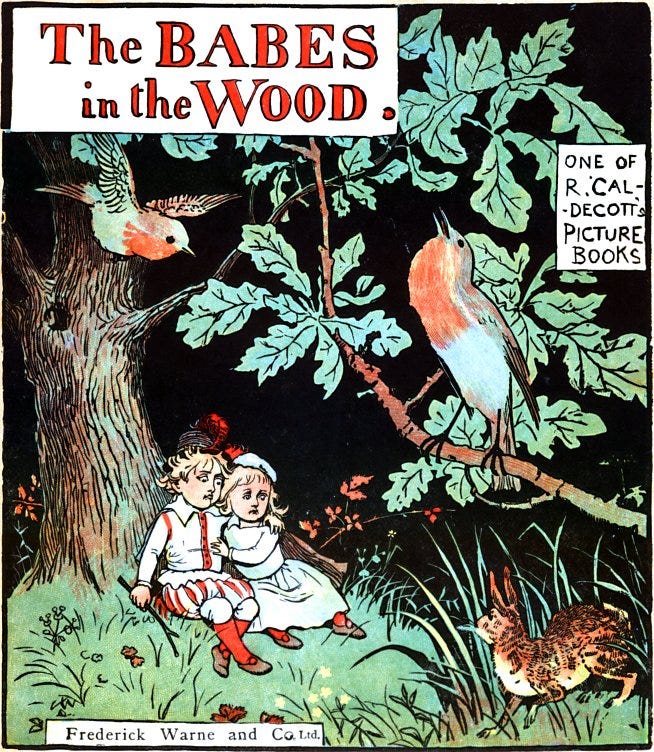

While these woods are important for their mix of oak, hornbeam, ash and coppiced hazel, and their mention in the Domesday book, they are known for something rather more sinister: it is setting of that dark fairytale, Babes in the Wood.

The town sign of Watton, depicting a leaping hare over a barrel, along with the babes. The ancient word “watt” means hare and “tun” a barrel. It seemed especially fitting that I should encounter a hare as I was walking.

In the tale, the babes are entrusted by their dying father to a wicked uncle, who hires two local scoundrels to dispatch them so that he can inherit their fortune. The children are led into the wildwood in the depths of winter, but when they reach its dark heart, one of the villains realises he cannot commit this deed. Instead he kills his fellow rogue and flees, telling the children he will return for them. But of course he never does. The babes wander deeper into the wood, become helplessly lost, eventually curling together amidst the roots of an ancient oak, to die in the bitter chill. The only tender note is that the robin, distraught at their demise, covers their bodies with fallen leaves. It is a cruel and disturbing story.

An illustration by Randolph Caldecott published in 1879 (1846 - 1886)

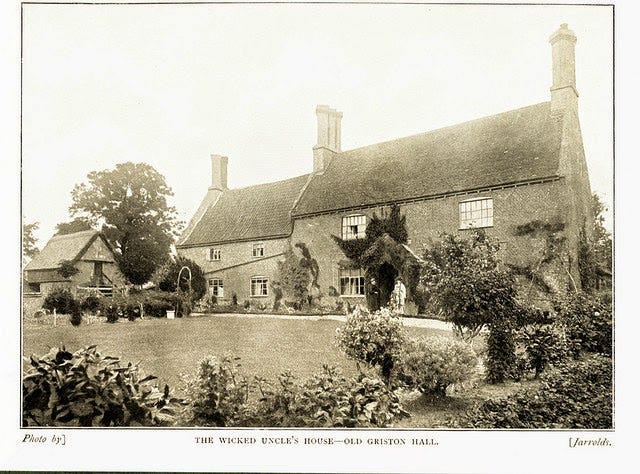

In the roots of this fairytale, some truth can be found. In the mid 16th century, a scandel that took place at Griston Old Hall, which then bordered the wood, where Thomas de Grey is meant to have murdered his eleven year old ward for his inheritance. This local legend is then picked up in 1595 by Thomas Millington, a printer from Norwich, who published it as a hugely popular broadsheet ballad. It gained further momentum when the next owner of Griston installed an carved overmantel depicting scenes from the story in 1597, and although this was lost in a later refurbishment, it is remembered clearly in accounts from the late 19th century. The tale sparks to life again in 1879 when the vast oak, at whose roots the babes are meant to have perished, was struck by lightning. Sightseers took away shards of its splintered remains as souvenirs and now the site of the great tree has been lost amongst the undergrowth.

Old Griston Hall, residence of the “Wicked Uncle”.

Like all myths, it is a tantalising mix of truth and fable. The name “Wayland” became locally corrupted to “Wailing” as at dusk the plaintive cries of the children are meant to be heard and seen flitting amongst the trees. There are still local folk who won't walk in the woods. M. R. James mentions the place in his guidebook to “Suffolk and Norfolk” and it is thought that his story “Wailing Well” might have come from this.

Such fairy tales tap into our fear of being lost among trees, of feeling vulnerable and cut off from safety. Little Red Riding Hood is warned not to stray from the path. Hansel and Gretel leave a trail of breadcrumbs to help find their way home, but these are eaten by the birds. Snow White is led into the forest by the Huntsman, but when she escapes the trees turn on her, entangle her feet and scratch her face. Secrets are buried in woods, in the hope of them never being discovered.

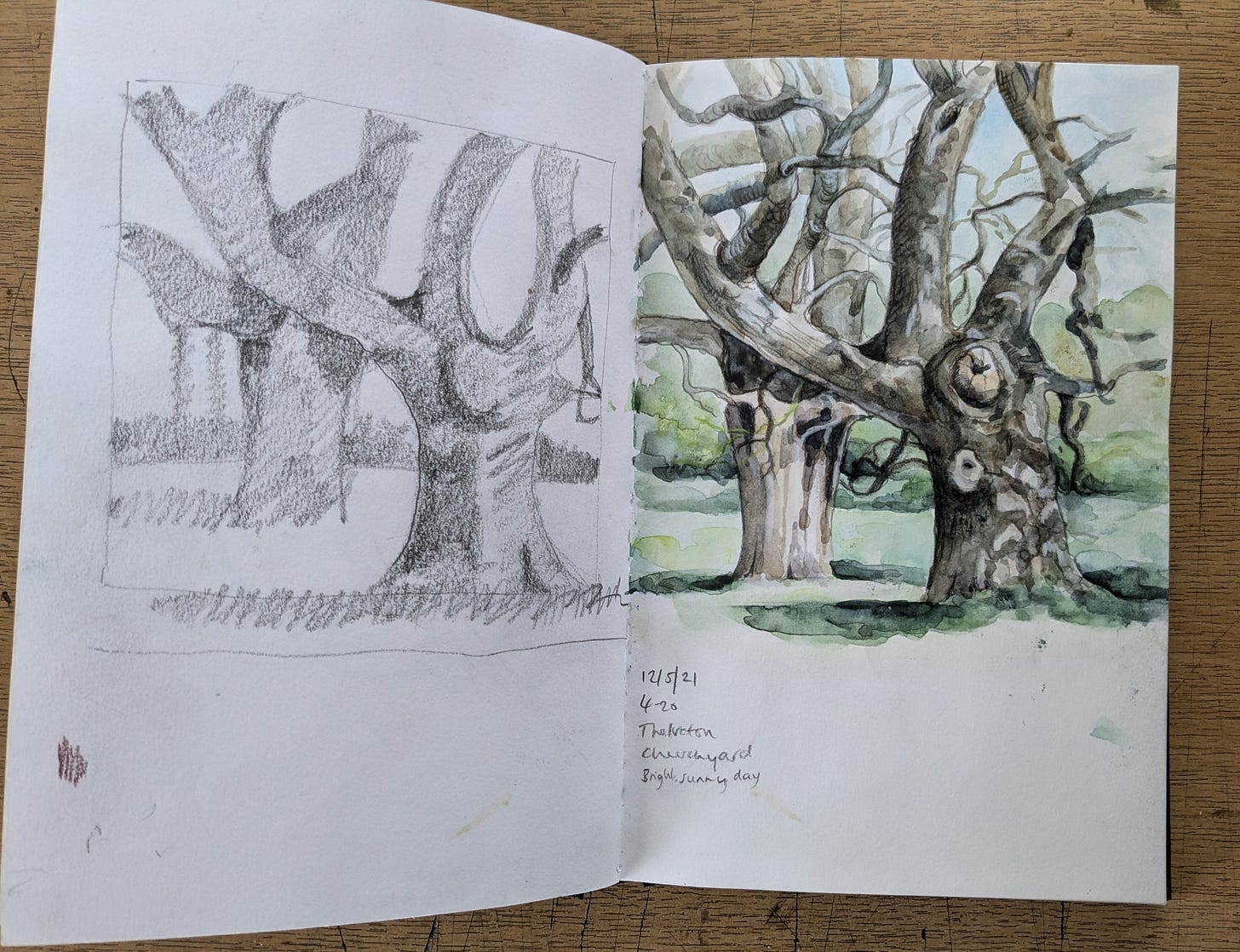

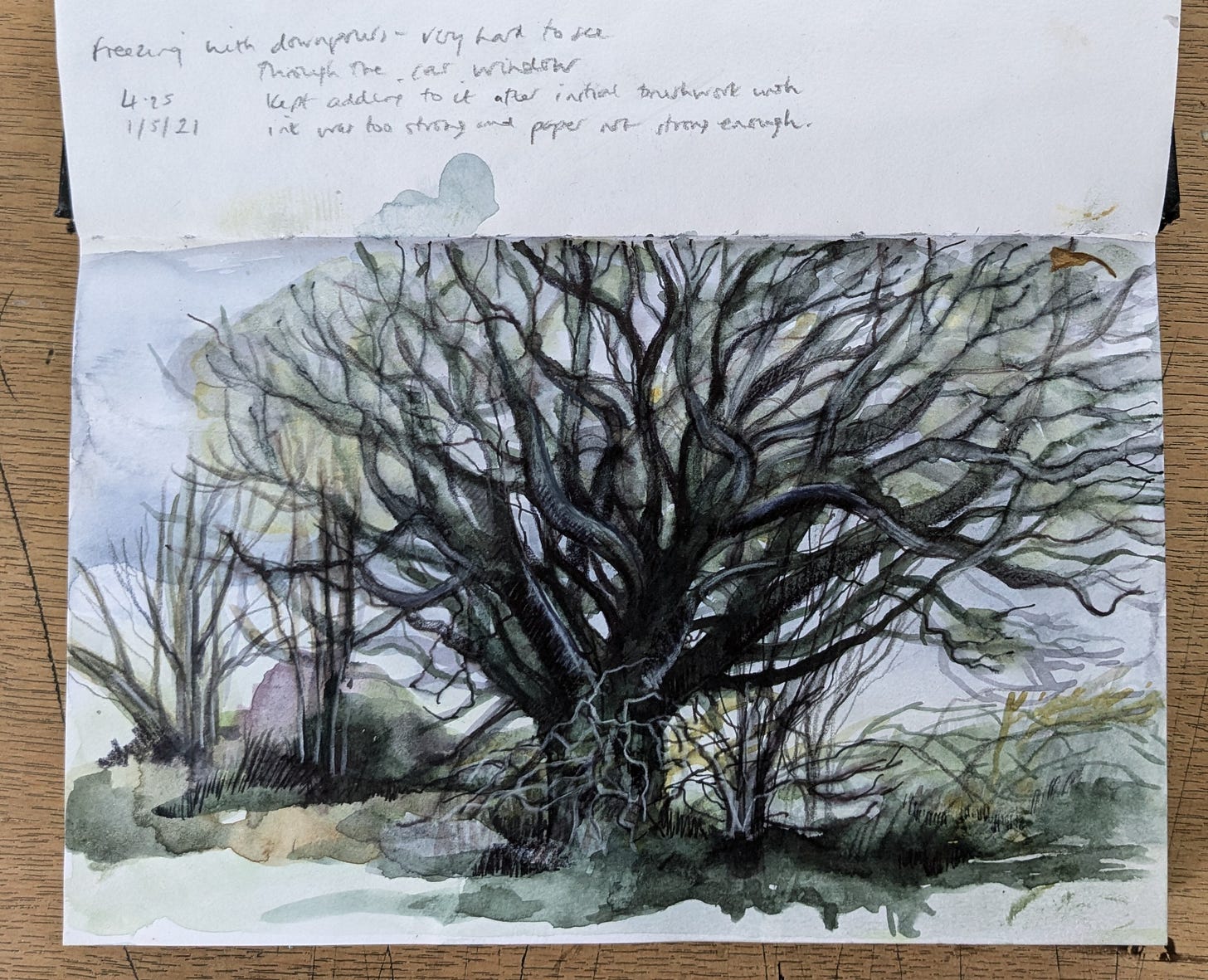

This primeval sense of unease has never left us. While I feel great comfort and peace while walking in the woods, I cannot help but feel a sense of apprehension when I am drawing there and wish I could just disappear amongst the branches to sketch undisturbed. Drawing alone in woodland is something I rarely do, eventhough it is the place where I want to draw most. I often read of male painters who contentedly paint outdoors in remote places, but for a female it is more problematic. I never feel fully at ease as one ear is always alert to strange sounds. My favourite drawings of trees have always been drawn from the security of my car, but that, of course, is somewhat limiting!

So much of our land would once have been woodland and certainly Wayland would have stretched far further than it does today.

The lives we have chosen are prising us apart from the natural world, and we are more likely to experience a woodland through watching Countryfile than by breathing in the actual, living trees. Most of us are cloistered far from any woods, and the ancient connections have faded.2

Yet sitting alongside this fear, woodlands too have been seen as a place of refuge where fears and hurdles can be overcome. While writing this I suddenly remembered a book called “Hollow Tree House” by Enid Blyton which I read as a young child. It had a profound effect upon me. It tells of Susan and Peter’s escape from their wicked aunt to live in the hollow of an ancient oak. I was entranced by the idea of living within the arms of a tree, it didn’t seem remotely scary. I remember weeping uncontrollably when the children were rescued and had to leave the arboreal home.

While walking through Wayland, on that dark, damp and gloomy day I tried hard not to think of those childen lost among the thicket. Although it is only 34 hectares square, it feels so much larger because of the density of growth. The path seems to have been deliberately forged to disorientate. As it winds through the dark interior, I soon lost sense of how far I had come.

But my fear quickly gave way to a sense of wonder. Instead of peering over my shoulder, instead I found myself crouching to look at the fungi that had emerged from the coppiced logs. My sketchbook remained in my pocket, but I found myself photographing these treasures that seemed to appear at every turn, getting damp knees as I crawled to identify what I saw with my app. It became not a place of menace, but enchantment.

Candlesnuff fungus (Xylaria hypoxylon) held in the bowl of a coppiced hazel

King Alfred’s Cakes (Daldinia concentrica) seeping out of the fallen logs

A hare lolloped across my path. I heard the sharp alarm of a wren. Grey squirrels cried out from the high canopy.

As my walk came to a close, the paths opened out and winter moths danced amongst the soggy seedheads. Patches of sunlight filtered through and I was sorry that it was time to leave.

Then, just at its very edge, I saw the bare bones of a stricken tree, its bark red and stark against the soft green leaves of its companions. I shivered, it was time to go home.

Charcoal sketch made from the comfort of my car.

Something to read

After enjoying “A Fugue in Time” so much, this month I hit several duffs, ( and life is just too short to struggle through unappetising books), so instead I shall turn to an old favourite, “Lolly Willowes, or The Loving Huntsman” (1926) by Sylvia Townsend Warner. It begins with “Aunt Lolly”, one of the many single women following the Great War, who goes to live with her brother and his family following their father’s death. As middle age looms, she decides to up sticks and defy them to live independently in the village of Great Mop where, once again, the archetype of the wildwood reoccurs. It is then that the novel takes an unexpected turn, and I won’t spoil it for you, but I wish I could read it again for the first time to be bewitched once more. Each year I buy some bronze chrysanthemums in honour of this defiant, subversive heroine. There is also a BBC radio play of the novel here.

This leads me to “Singled Out” by Virginia Nicholson which tells the story of those women, raised in the expection of marriage, but found themselves spinsters following the lost generation. It is a remarkable and moving book based on oral testimonies.

Something to listen to

A Podcast to the Curious I discovered this after going down a rabbit hole searching for the link between Wayland and M.R. James. Hosted by Jamesian enthusiasts Mike Taylor and Will Ross, each episode discusses a story or aspect of M.R. James work. They wear their erudition lightly and it is a real hoot. I ended up listening to one episode after another, seeking out my favourites.

I couldn’t resist adding this beautiful recording. It is from Kipling’s “Puck of Pook’s Hill” and was renamed and set to music by the folk singer Peter Bellamy in 1970.

Something to watch

Charlie Cooper’s “Myth Country” I have yet to watch his award winning comedy series, “This Country”, but having seen this, I will certainly now remedy that. In each half hour episode, he explores the weird and surreal realm of British folklore and those who investigate it. The first programme goes in search of Black Shuck, the demon dog that roams East Anglia. Charlie visits Blythburgh church, and his overnight stakeout, in the hope of capturing the beast on film, is a delight.

Thank you again for joining me this month. Next week I am off drawing in the Peak District, where I am hoping some peace and a change of landscape will help ignite a spark. If you enjoyed reading this , don’t forget to press the “Heart”, as it really helps my work to be seen and lets me know that it has been read, which is always cheering! Your support here makes my work possible, so please consider subscribing. I shall see you again in a couple of weeks.

The Way Through the Woods (1910)

They shut the road through the woods

Seventy years ago.

Weather and rain have undone it again,

And now you would never know

There was once a road through the woods

Before they planted the trees.

It is underneath the coppice and heath,

And the thin anemones.

Only the keeper sees

That, where the ring-dove broods,

And the badgers roll at ease,

There was once a road through the woods.

Yet, if you enter the woods

Of a summer evening late,

When the night-air cools on the trout-ringed pools

Where the otter whistles his mate,

(They fear not men in the woods,

Because they see so few.)

You will hear the beat of a horse's feet,

And the swish of a skirt in the dew,

Steadily cantering through

The misty solitudes,

As though they perfectly knew

The old lost road through the woods...

But there is no road through the woods.

Rudyard Kipling

Peter Fines,“Oak and Ash and Thorn”, One World, 2017.

Such fabulous art and I reckon that, though it may feel as if you’ve lost your way, it’s actually setting out a path for you…a trail to follow.

I was thinking about what you said, how we feel about woods and the sensations they awaken. We are so lucky to have a very special woodland within walking distance of our gate and reached by a green lane, which we’ve walked for thirty years, and I have to say it now feels like the most benevolent, cathedral-like space. We know every inch, every tree and every season and perhaps the advantage is its seclusion. It would be rare to meet anyone else there and if we did we’d know them. In particular I love what we call the pixie pools…those hollows in the base where water collects. The dogs know exactly where they are too.

Such a lovely post, I wanted to chat about so much in it! Wayland's Wood made me think of Wayland's Smithy, the atmospheric long barrow off the Ridgeway in Oxfordshire, linked to Wayland, Saxon god of metalworking and mythic smith who will shoe your horse overnight if you leave it at the 'smithy'. I wonder if there is a connection?

There is something about woods that can be very contrary, I think - green, leafy and welcoming, but at the same time drear and a bit threatening when they're quiet. Deciduous woodland particularly shape-shifts through the seasons, and is scarcely the same place twice.

I was interested to see how at the moment you seem to be drawing twisted, gnarly trees - is that because that's what you see, or do you seek them out? I loved the prints of single leaves - they would be wonderful in unexpected colours...

And fungi! This time of the years is such a wonderful time to see them. I am just the same - constantly bending down, taking photographs, looking them up etc. I dont know how anyone can just walk past them!