While I was away in the Black Mountains, spring happened in my garden. When I left, there seemed to be barely a bud, and yet on my return, the garden was an exuberant mass of frothy pink blossom and bluebells pooled underneath the canopy. I felt a little cheated. It was wonderful to see, but dislocating. I had somehow missed the build-up and anticipation of this great event and I felt I had been dropped unceremoniously into another country.

My garden is a small chunk of what was once an old orchard. The land that slopes down to the Mere ( an ancient lake in Diss’ town centre) was once used as market gardens, but now only a patch of this land remains. Over the past twenty or so years I have watched the surviving apple trees in adjacent gardens fall, or be removed, but I take my custodial duty very seriously: they are a link to the garden’s history that I would hate to lose.

A tiny oil sketch of the apple bloosom that overhung my Norwich studio 25 years ago

The oldest tree is suspected to be at least one hundred and fifty years old. It must have once have lost balance as a section of the trunk lies on its side, but it lifts up again and its branches span much of the garden. It has been identified as a Blenheim Orange, a variety dating from the 18th century, that is meant to be a cooker, though is quite tasty to eat straight from the tree. Another is Ribston Pippin, dating back to 1785, also known as the Glory of York, a popular Victorian variety and probably the parent of our Cox’s Orange Pippin. The third, the Vicar of Beighton, is a true Norfolk apple produced locally in 1890, but the final of the four trees remains unnamed, but is no less loved for that.

Each year more branches die, and are removed, and in spite of the increasingly soggy garden in winter and summer droughts, they fight on, thankfully.

A sketchbook page of my Norwich studio tree

My last garden in Norwich was also blessed with ancient fruit trees and one spread across the roof of my tiny studio / shed at the bottom of the garden. Knowing I would be writing of my trees, I pulled out a sketchbook from 25 years ago, and immediately I was back sitting under its branches, with the bees in the blossom, and the bright blue sky overhead. I pulled out more recent ones, one from during Covid, when I sketched their knotted trunks and discovered a Great Tit’s nest in a bowl of the trunk.

A Great Tit delivering food to its young in the bowl of the apple tree

A pencil sketch of one of my apple trees

In a Shoreham Garden, Samuel Palmer c.1830 Watercolour, gouache and Indian ink

Copyright The Victoria and Albert Museum

But if you could conjure up the sensation of what it is to see apple blossom in April, this image is it. Samuel Palmer had recently moved to the Vale of Shoreham, in Kent, following a legacy from his granddfather, giving him finanancial independence and the freedom to create as he wished without the burden of producing work for sale or exhibition. These few years from 1826 - 1833 were to be the most creative of his life.

A self taught artist, Palmer was always trying to push the limits of his materials, and was determined to go beyond the conventions of watercolour painting of this period. Preceeding this painting he had created idiosyncratic drawings of pastoral scenes in sepia ink, mixed with gum arabic to increase its thickness. Each section is heavily patterned and outlined in strong strokes and then the completed work varnished to add cohesion.

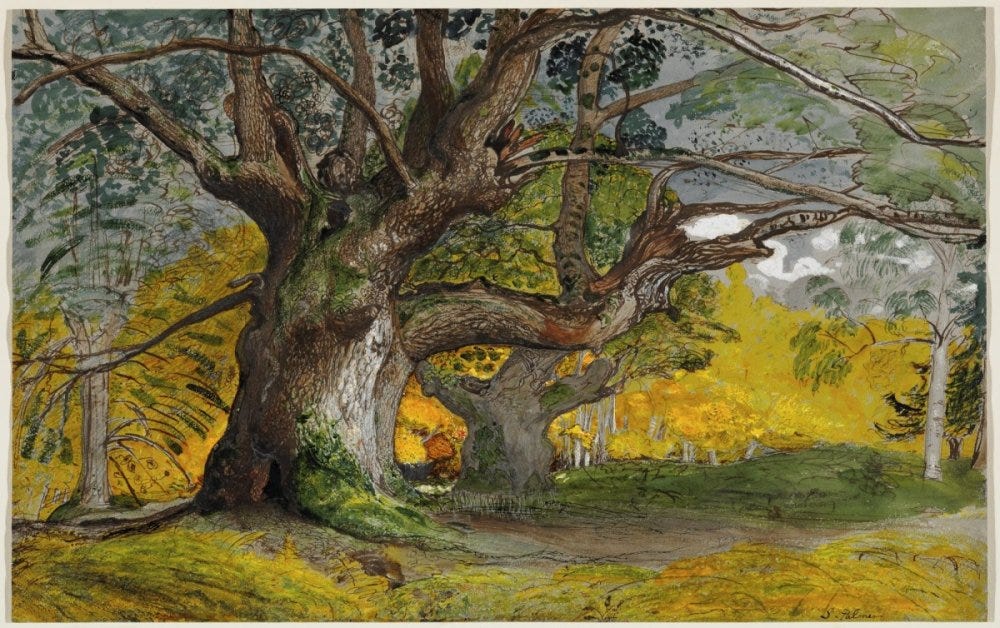

Oak Trees, Lullingstone Park, 1828, ink and watercolour Copyright National Gallery of Ottawa

Then a burst of colour appeared in his work in a series of remarkable drawings of a grove of oaks in Lullingstone. They are lit by the same vibrant egg yellow that appears in “A Shoreham Garden” and the descriptive sepia, knobbled lines of the oak’s trunk are fired with energy. You can see Palmer struggling to break free from the mould of creating naturalistic studies as he began by mapping out the scene in graphite and fine pen lines and then strengthening and exaggerating in bolder, broader strokes of ink.

"I will, God help me, never be a naturalistic by profession." Palmer in a letter to George Richmond, October, 1828.

None of these studies were made with the intention of being sold, and some remain unfinished compositions. With each work, you can see him stretching his wings and extending his ability to create vigorous expressive lines and marks and they increasingly convey the intensity of his experience and feelings about Shoreham.

And then the following Spring he painted, “In a Shoreham Garden” that uses the same hot pink and yellow palette of his earlier oak paintings, but adds an explosion of thick, clotting blossom. The pigment is used in impasto blobs, each clump outlined in ink, and has been likened to Jacobean stumpwork embroidery in the way it emerges from the paper.

You can see that it is an old tree, with its nubbly bark and cadmium lichen and it is clearly a warm April day, with the deep shadow on the path cast by the flower border. The plants are difficult to identify, and are they verbascum planted at its feet? The graceful figure, clothed in vibrant red, looks upwards as she lifts her face to the sun. It is a painting that celebrates the warmth and fecundity of spring.

I find it incredible that these works were never exhibited in Palmer’s lifetime, but were kept hidden in a folder he called his “Curiosity Portfolio.” Did he not realise their worth or were they viewed with such affection that he couldn’t bear to share them with others? Looking back on this period in 1871, he said, “the beautiful was loved for itself”, but he also believed that they were a divergence from his path as an artist and yet now they are the works held in greatest affection.

Each year I intend to paint the blossom in my garden, and each year I don’t. It feels so overwhelming that trying to pin the experience down on paper feels impossible. It overarches the whole garden and each year I feel thankful for it. This year, as I move towards a significant birthday, it seems especially poignant, as though its spectacle is undeniably overwhelming, there is something unbearable about its fragility and emphemerality. Each year I am reminded of an interview I saw many years ago with the writer Dennis Potter in what was to be his last interview after being diagnosed with cancer. His words about seeing blossom comes at 6 minutes 50 seconds, but I urge you to listen to it all. It is uplifting, moving and powerful viewing and after 30 years, I have never forgotten it. At blossom-time I think of him and feel a sense of enormous gratitude to be able to appreciate its joy again.

I see it is the whitest, frothiest, blossomiest blossom that there ever could be, and I can see it.

Something to listen to

I am not sure where I heard about this, but I am so glad I did. I have never been very good at identifying bird song and, as a consequence, this has been the most enriching discovery. The Merlin app allows you to record birdsong and it picks out the individual birds and identifies them, highlighting each song as the bird sings! As the coming weeks are the best time to wrench yourself out of bed to listen to the dawn chorus, I gave it a trial run while in Wales. Below you can hear the wren, a blackbird, a blackcap and a Mistle Thrush:

Something to read

And to end Louis MacNiece’s “Apple Blossom,” another reminder of all that is precious.

Apple Blossom

The first blossom was the best blossom

For the child who never had seen an orchard;

For the youth whom whisky had led astray

The morning after was the first day.

The first apple was the best apple

For Adam before he heard the sentence;

When the flaming sword endorsed the Fall

The trees were his to plant for all.

The first ocean was the best ocean

For the child from streets of doubt and litter;

For the youth for whom the skies unfurled

His first love was his first world.

But the first verdict seemed the worst verdict

When Adam and Eve were expelled from Eden;

Yet when the bitter gates clanged to

The sky beyond was just as blue.

For the next ocean is the first ocean

And the last ocean is the first ocean

And, however often the sun may rise,

A new thing dawns upon our eyes.

For the last blossom is the first blossom

And the first blossom is the best blossom

And when from Eden we take our way

The morning after is the first day.

(From Louis MacNiece’s ”Collected Poems”, 2013)

My garden with the overhanging branches of the apple tree with a glimpse of my studio through the branches

Thank you for your company here. If you have enjoyed this piece, it would be lovely if you shared it or subscribed. Your support is be greatly appreciated and allows me to keep going.

This is a fantastic read. Sitting here by my back window we are lucky to have quite a lot of birdsong and two apple trees in the back garden. One, a cooker which always blossoms first at the start of April and the second an eater (bit sharp) that comes in later just as the blossom on the eater is falling away for good. We did have 4 but two were planted in a very shallow spot and grew up against a high wall that they had started to push over in the neighbours so we removed them for safety.

We have only been here a few years but I have consistently found myself gravitating towards those trees and find the blossom to be an Incredibly uplifting sight at the start if spring. Definitely inspiring much writing and photography.

This has been a great post, thanks for sharing.

This was such a beautiful read Deborah! Filled with so much beauty and interesting information. Loved your apple blossom painting and your lovely pencil sketch of an apple tree. So much history attached to trees, not to mention beauty as well. I was just gifted the very popular book "The Hidden Life of Trees" by Peter Wohlleben and I'm really looking forward to reading it. Have you read it yet? Thanks so much for your generous shares! xx