It’s all about love and hard work - Shirley Hughes

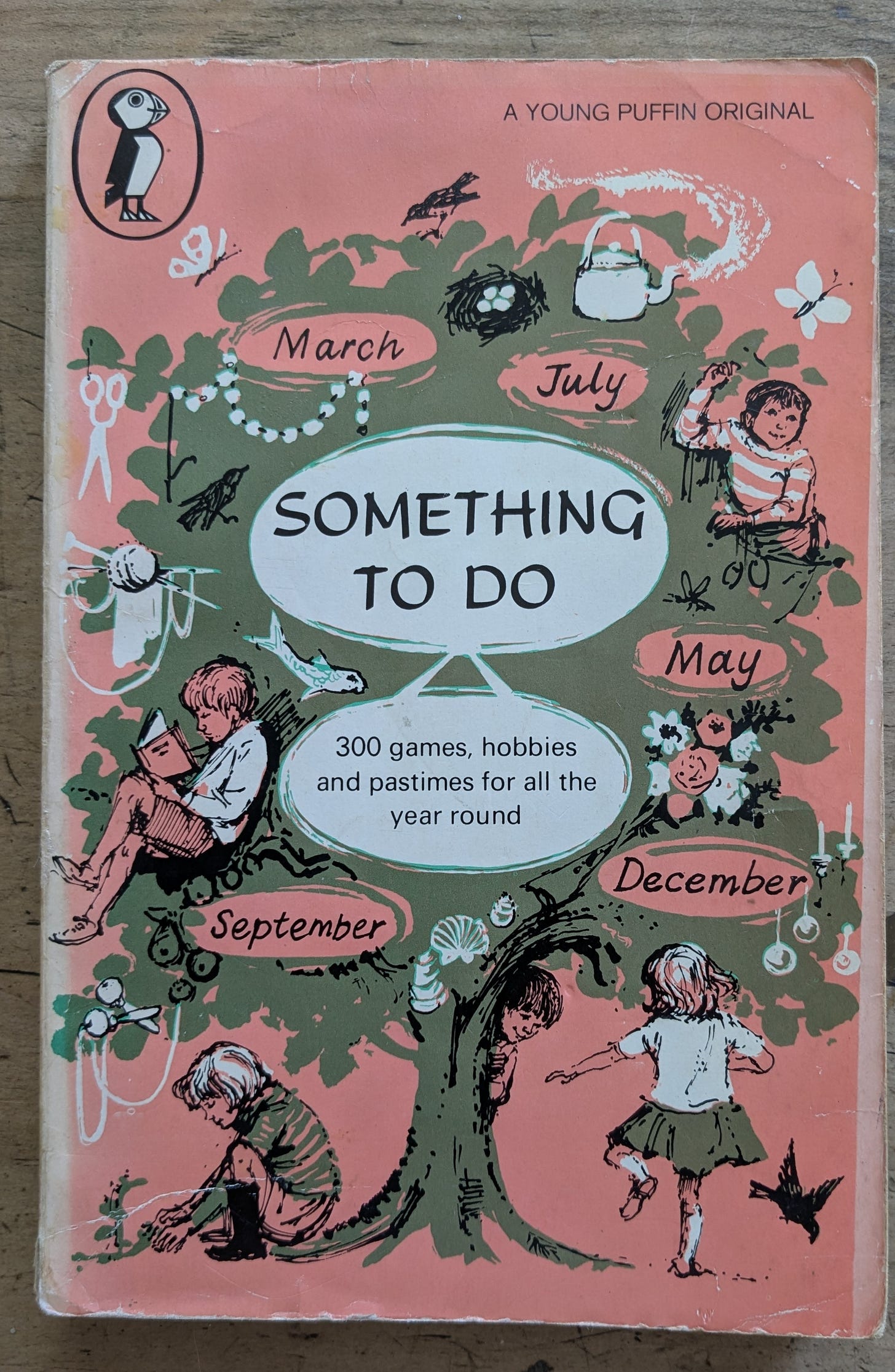

Sitting in a pool of Puffin books, this is the one I loved most of all.

Now yellowed with age, faded and creased with love, it was a repository for endless days of doing. Bought with my pocket money from the now lost Midland Educational, it could have been made for me.

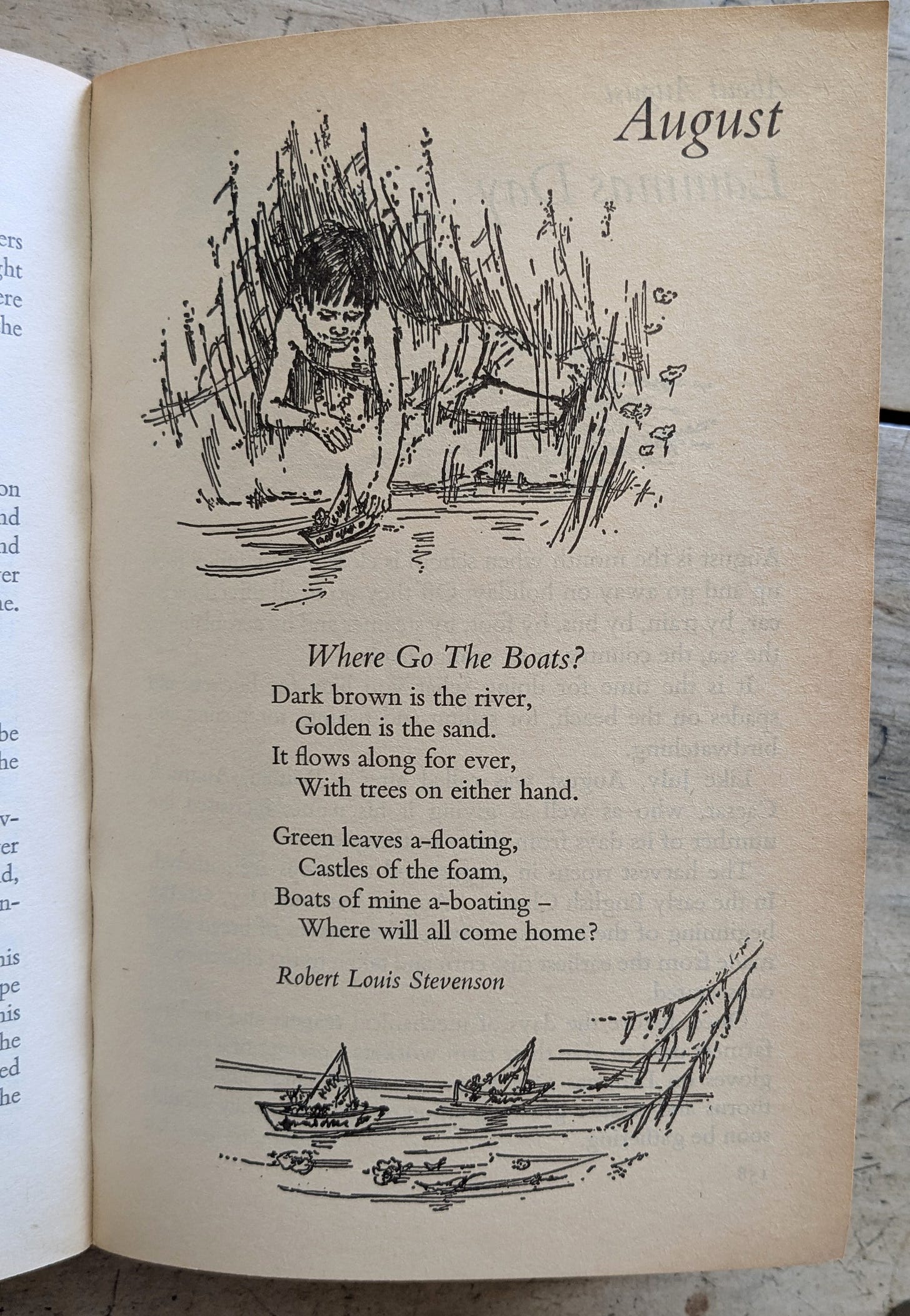

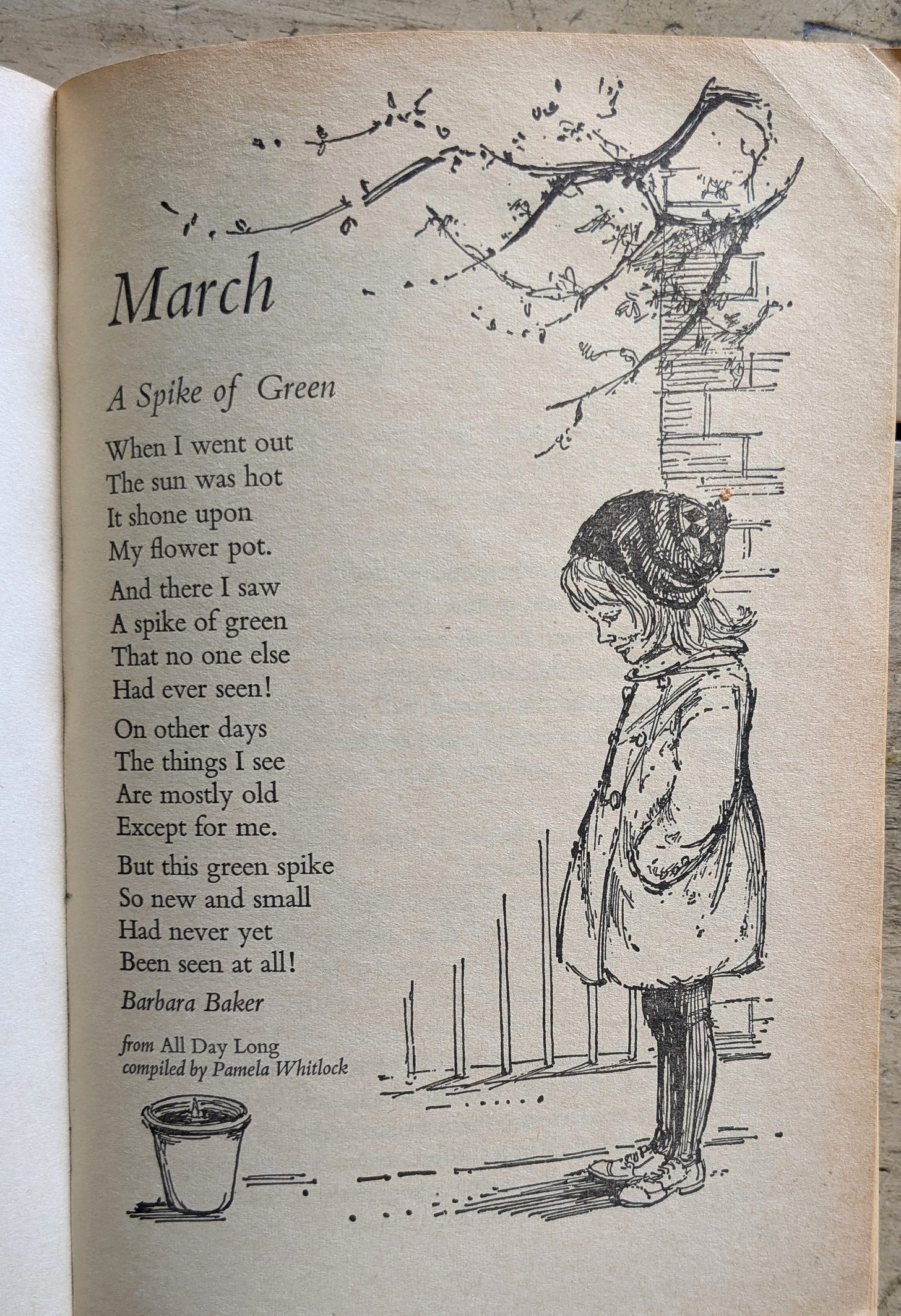

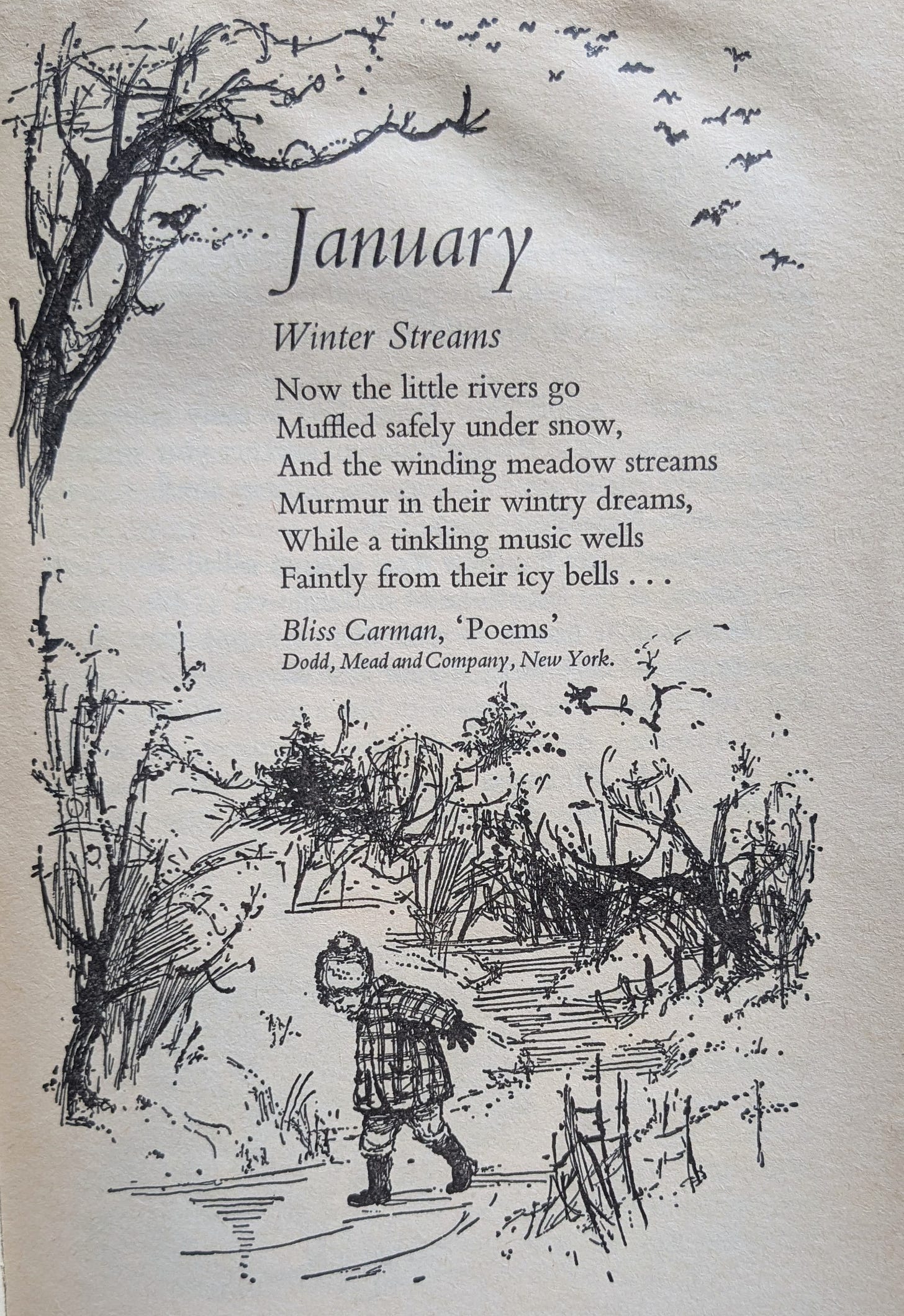

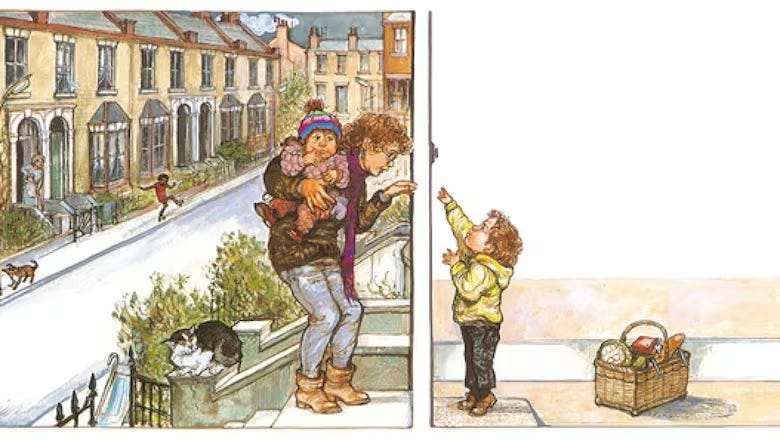

Two of my favourite illustrations by Shirley Hughes that headed each month in “Something to do”.

Published in 1966, as part of the “Young Puffin” series, it offered a year of delights: poems, nature notes, things to make indoors, and outdoors, all arranged in monthly chapters. Looking through it now, I suspect I didn’t follow the seasonal order. I simply made whatever caught my imagination or could be conjured from my “making” box.

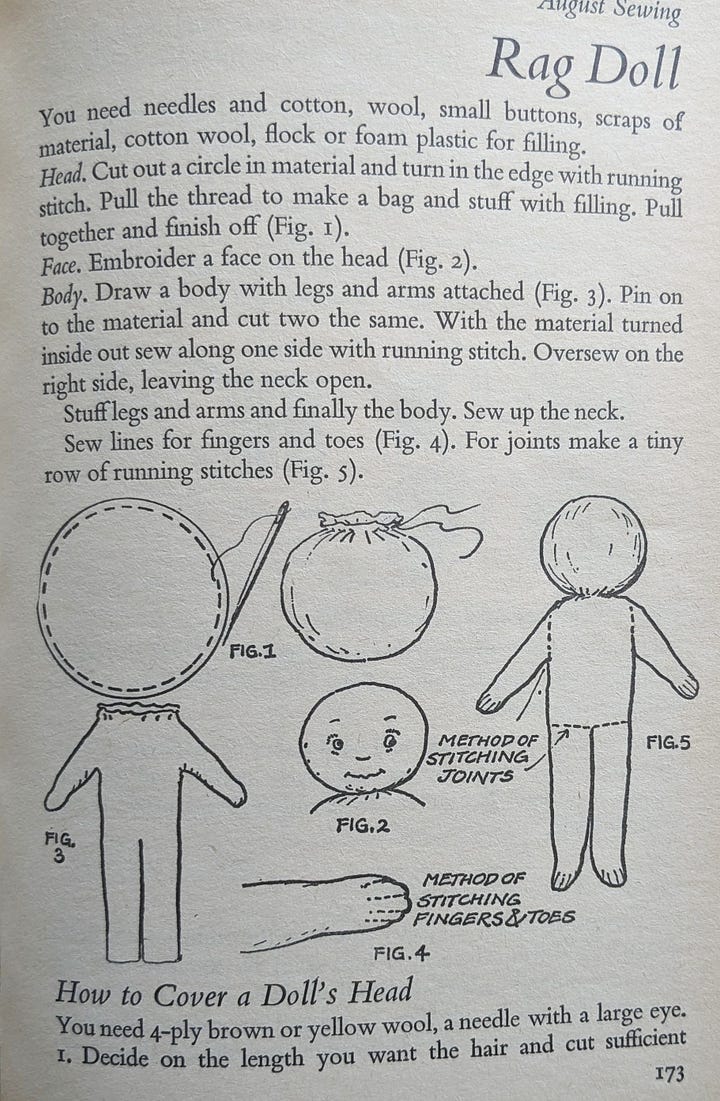

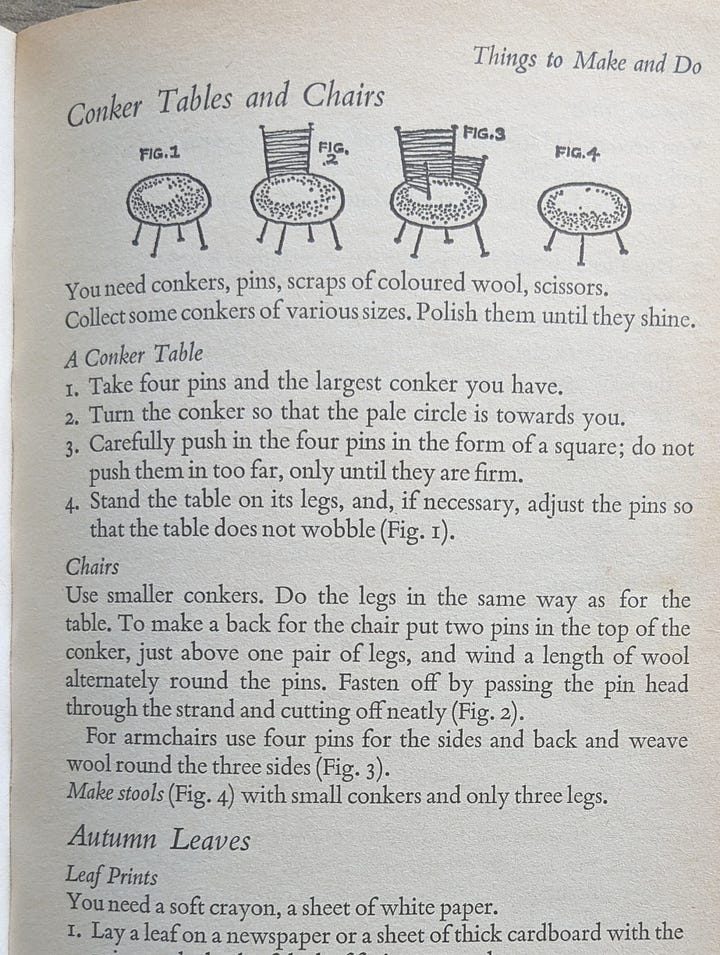

When I saw the pages on how to make a ragdoll, my heart skipped a beat. I had forgotten all about her. She was constructed from an old sheet and begged-for fabric scraps (“Have you got any bits of stuff, Nan?” was my frequent, plaintive cry) and was sewn with tiny, careful stitches. There were woollen pompoms too, a handkerchief mouse and fat little conker chairs that looked like miniature Habitat furniture. Each activity was inventive and satisfying, encouraged resourcefulness and thrift and each required little expense. To a pre-technology child it was the perfect antidote to summer holiday boredom.

It was written by the mysterious “Septima” who is described in the Introduction as “we, the seven authors”, but who were they and why the secret? It was edited by Nancy Shepherdson, who is equally elusive , and even the creator of the diagrams, W.E. Bland, has vanished without a trace.

W.E Bland’s helpful diagrams of the little ragdoll and the conker chairs

But the illustrator of the poems and outdoor activities was not so easily lost to history. As a child, the name meant nothing to me; I had not yet encountered Dogger, Tom, Lucy, or Alfie. But thankfully, now I have, for these were drawn by the beloved illustrator and writer Shirley Hughes.

In the case of Susan Einzig, I would rush down alleys, to find them all blind, but in this case, there was a feast to discover and follow and I have spent many happy hours watching films and reading interviews from her long career, and gathering a rising tide of notes. I hung on to every word, noting down quotes, all of which seemed impossible not to share. There was so much I learned from this generous, open hearted illustrator and, at a time when lightness and joy are scarce, she has been wonderful company.

Self portrait by Shiley Hughes

So where to begin? She wrote over 50 books, illustrated more than 200, sold over 11 million copies and has been translated into 13 languages. And she wrote her first novel at 84. Her children’s picture books are unsentimental, they capture the small triumphs and tragedies of a small person’s life and are borne from a lifetime of drawing and looking closely. She never took photographs, instead using her sketchbook to build a bank of memories that could be plundered for infinite images. While there was little she could not draw, she is best known for her images of the lives of young children, their posture, their rapid movements and interactions.

But she began far away from this tiny world, in fashion illustration. Leaving school at 17 she enrolled at Liverpool Art School -a choice her mother dismissed as a “time-filler”- until a suitable husband could be found. Shirley, however, had different ideas. Though she stayed there for just a year, it was “the act of drawing every day, however inept and disappointing the results… It took root, a habit, an addiction, a satisfaction, a counterpoint to life which established is impossible to break”.

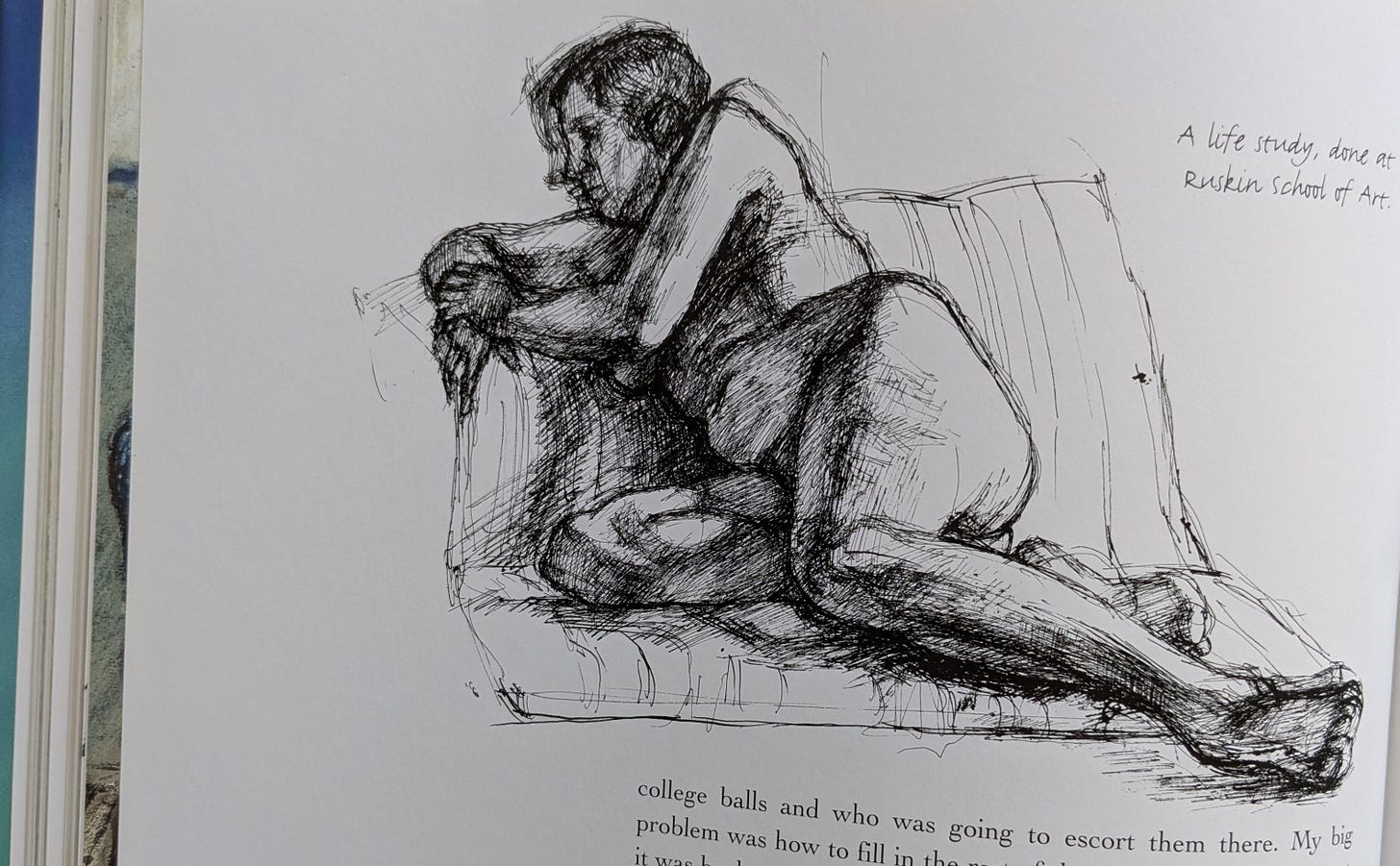

This was followed by a move to Oxford to the Ruskin School of Fine Art, which she chose on the basis that it had an ice rink (there wasn’t one) and instead she found “an art school with a vengeance”. During the 1940’s, drawing was fundamental to a fine art education and while spending hours initially drawing casts, and then on to the life room, she found it was not “fuelling the white hot fire of artistic invention” but it gave her the opportunity to fill “a huge money bank” in her head and the ability to “conjure up a gesture or a fleeting movement” in an instant; an invaluable resource for the future illustrator.

Two teachers “turned the lights on”. The first was Jack Townend, from the lithography department, who first suggested to her that book illustration might be something she should try. There was no training and so each evening she set herself projects through which she could learn. Using a combination of bold, fine line and the smudgy tonal qualities of the lithograph, she began to create drawings from her favourite books, from Jane Eyre to Anna Karenina, each completed on a drawing board on her knee in her bedsit.

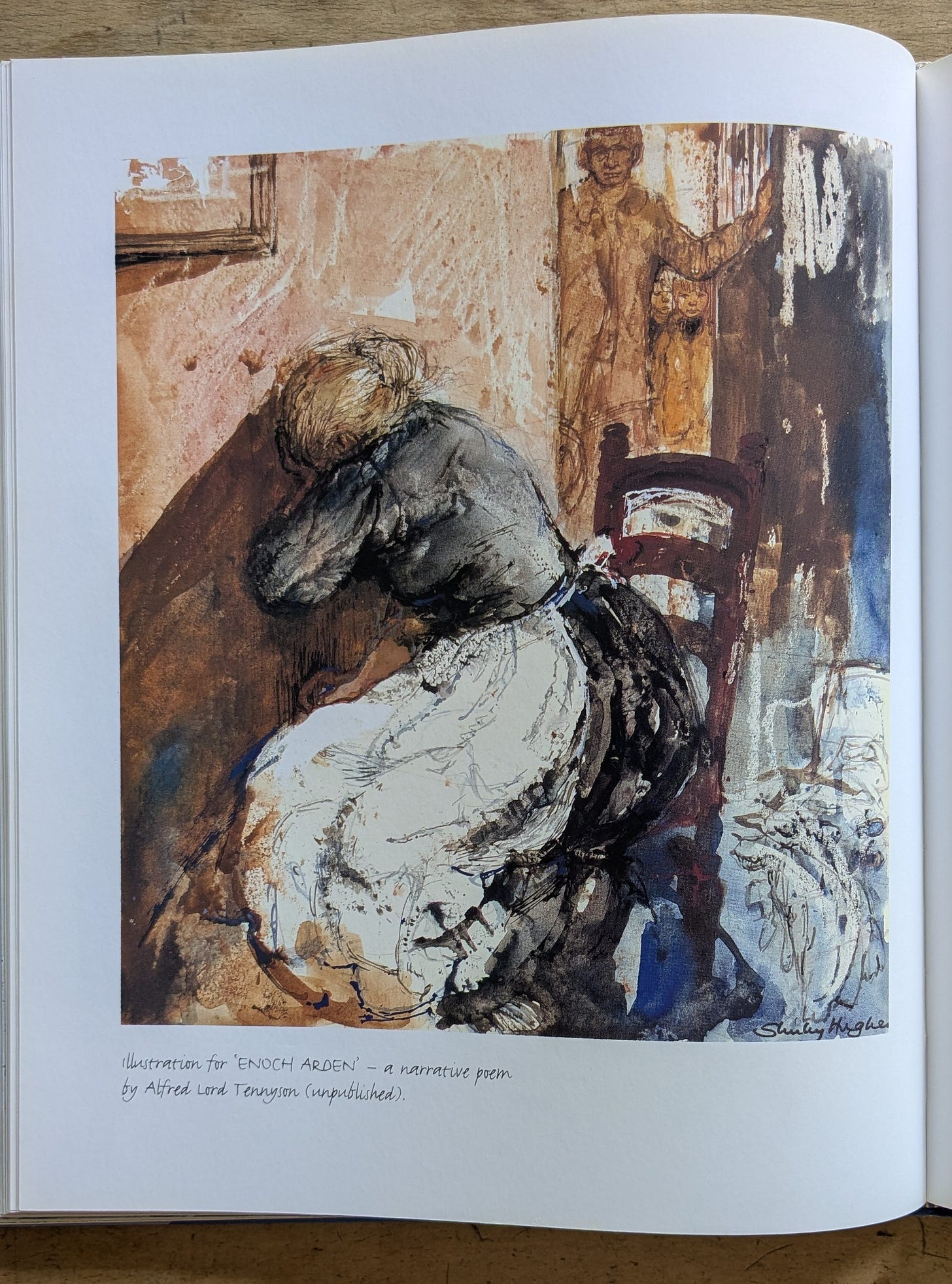

Using candlewax as a resist, with ink, watercolour and gouache, this is one of her experimental illustrations, that is alive with energy and emotion

The other teacher was Kenneth Clark, who would go on to present the ground breaking BBC Civilisation series, who gave lectures in art history as the Slade professor. Though he had “an aura of enormous distinction,” and “didn’t suffer fools gladly”, he communicated the beauty of art “and expected you to share it”.

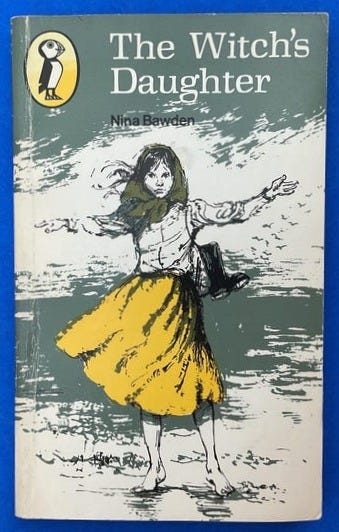

A Puffin from 1969, one of her early covers, and a particular favourite - such an efffective use of a limited palette, or “spot colour” , and exquisite line work

From the start, Shirley grasped each opportunity with a single minded determination. Her daughter, the illustrator Clara Vulliamy, described her as “driven and hardworking” but what is also clear is how much she loved what she did. She worked hard to succeed because she had found what set her alight.

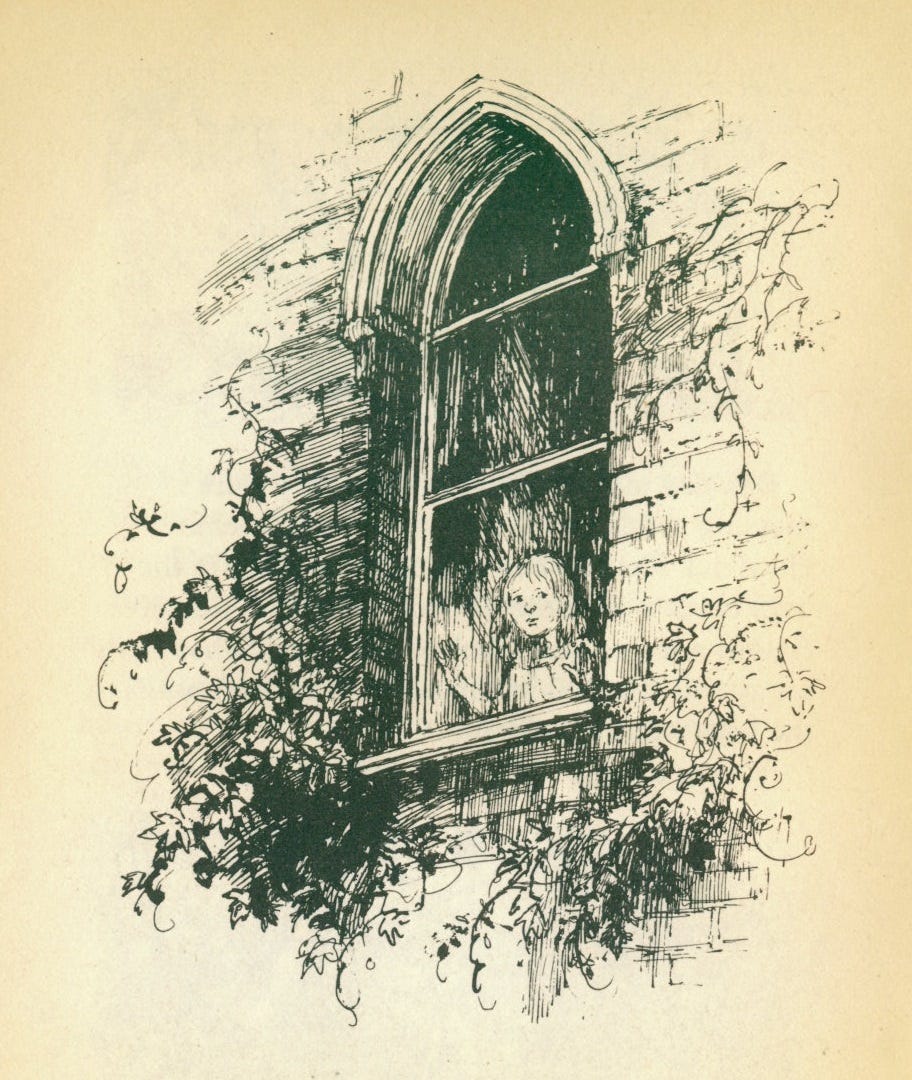

From “‘It’s too frightening for me”.

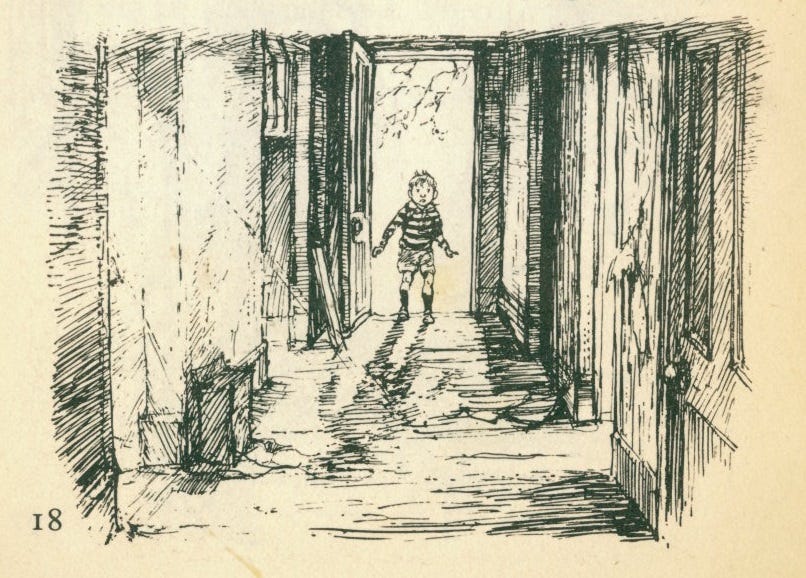

Again from “‘It’s too frightening for me”. I love the way the eye is led by the stong vertical lines to the nervous, tentative figure on the threshold, daring to go further.

At the end of her final year, the prospect of earning a living from her art, and trawling her portfolio around publishers loomed, but at the last moment, one of the college’s teachers, the lithographer and book illustrator, Barnett Freedman, called her aside. Though, she said, she had never spoken to him before, he offered to give her an introduction to publishers, if she cared to visit him in London. And this gave her a footing on what began “a rather wobbly and uncertain course” to her career.

What followed was not, of course, instant success but instead, years of hard work, drawing whatever she was asked and “many, many” book cover commissions. She had aspired, at the start of her career, to create illustrations for the Radio Times, just as Susan Einzig had. These pen and ink drawings for radio dramas taught her speed, flexibility and imagination. She would go on to create the cover for the Christmas edition, which she considered “a crowning achievement”.

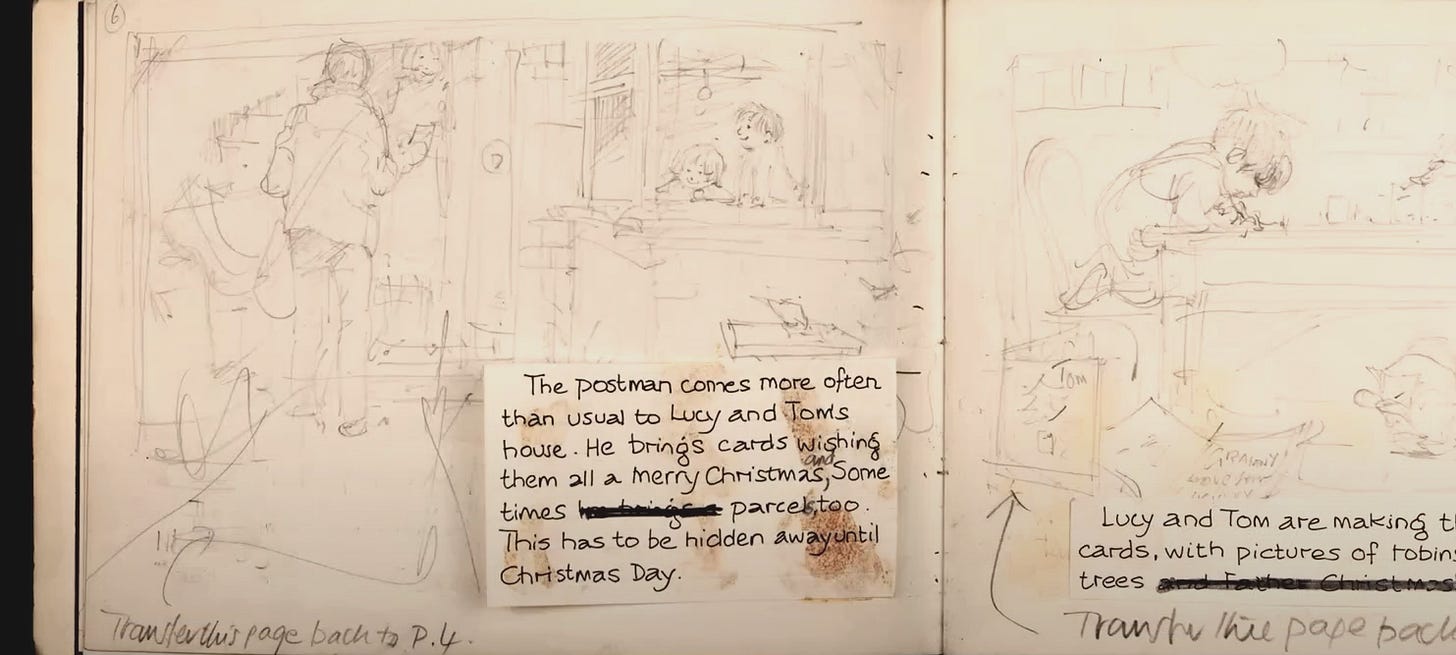

In 1959, she was asked to create her own picture book and, in 1960, “Lucy and Tom’s Day” was born. What made this book remarkable is its depiction of real life, its very ordinariness, and how she used the full spread of the landscape pages so that children could pore over the details. You can see the dummy copy here. After her death, her daughter Clara found in a trunk endless versions of the drawings for this book, scenes reworked over and over again, until Shirley felt she had got it right. There was even a sample copy, hand sewn, made to test the final drawings.

The “roughs” of “Lucy and Tom’s Day”

Her most loved and famous book “Dogger”, published in 1977, tells how Dave loses his precious toy, Dogger, the traumatic repercussions and the happy resolution. The real Dogger belonged to her son Ed, but Dogger remained with Shirley until her death, was kept in a hatbox, wrapped in a silk scarf and labled: “The original Dogger - VERY PRECIOUS.” You will be glad to know that Dogger has now returned to live safely with Ed.

In her early career, with three young children, and no help at home, she fitted her work around school hours, making the most of every moment. Her daughter tells how her beloved father John would “step up” at evenings and weekends to help his wife. Shirley later said how lucky she was to have a husband - an architect who “likes drawing as much as I do” - and who supported her career.

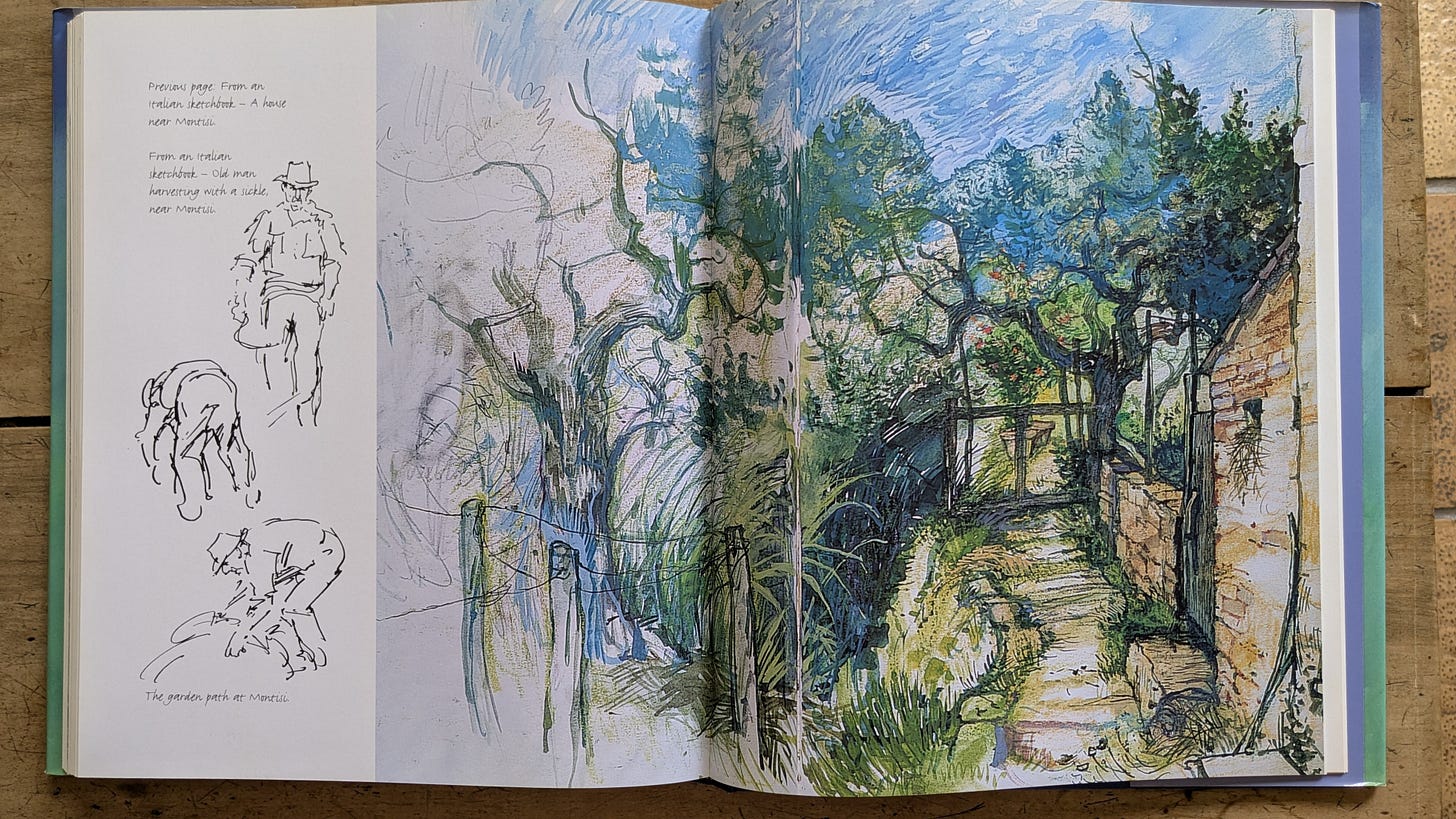

On holidays they would draw together: he sketching the grand sweep of a building while she would focus on some neglected corner or draw the children playing. She points out that he taught her perspective, which “had passed me by completely”, and joked, “I learned just enough to keep up appearances at least”.

When he died in 2007, she was devastated. To help fill the now gaping weekends that “were hell without him”, she began to write her first full length novels. Both were set in World War II: “Hero on a Bicycle” is set in occupied Florence, where she had spent time as a 19 year old just after the war, and “Whistling in the Dark”, is set in Blitz ravaged Liverpool, returning to the place she had grown up.

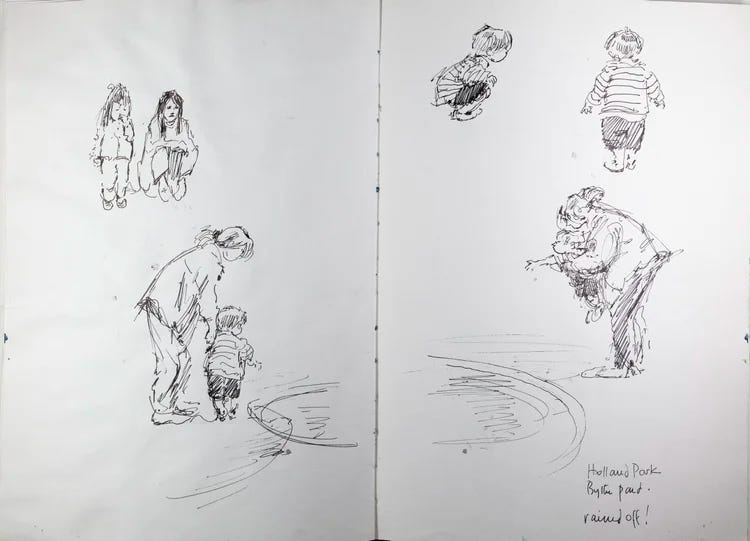

The habit of sketching, that had taken root at art school, never left her. In parks and playgrounds she would sit, “looking hard”, making rapid drawings of children, still and thoughtful, or noting “the way they all crouch down together when they’re looking at something very intently and then they all jump up and run off like a flock of starlings”.

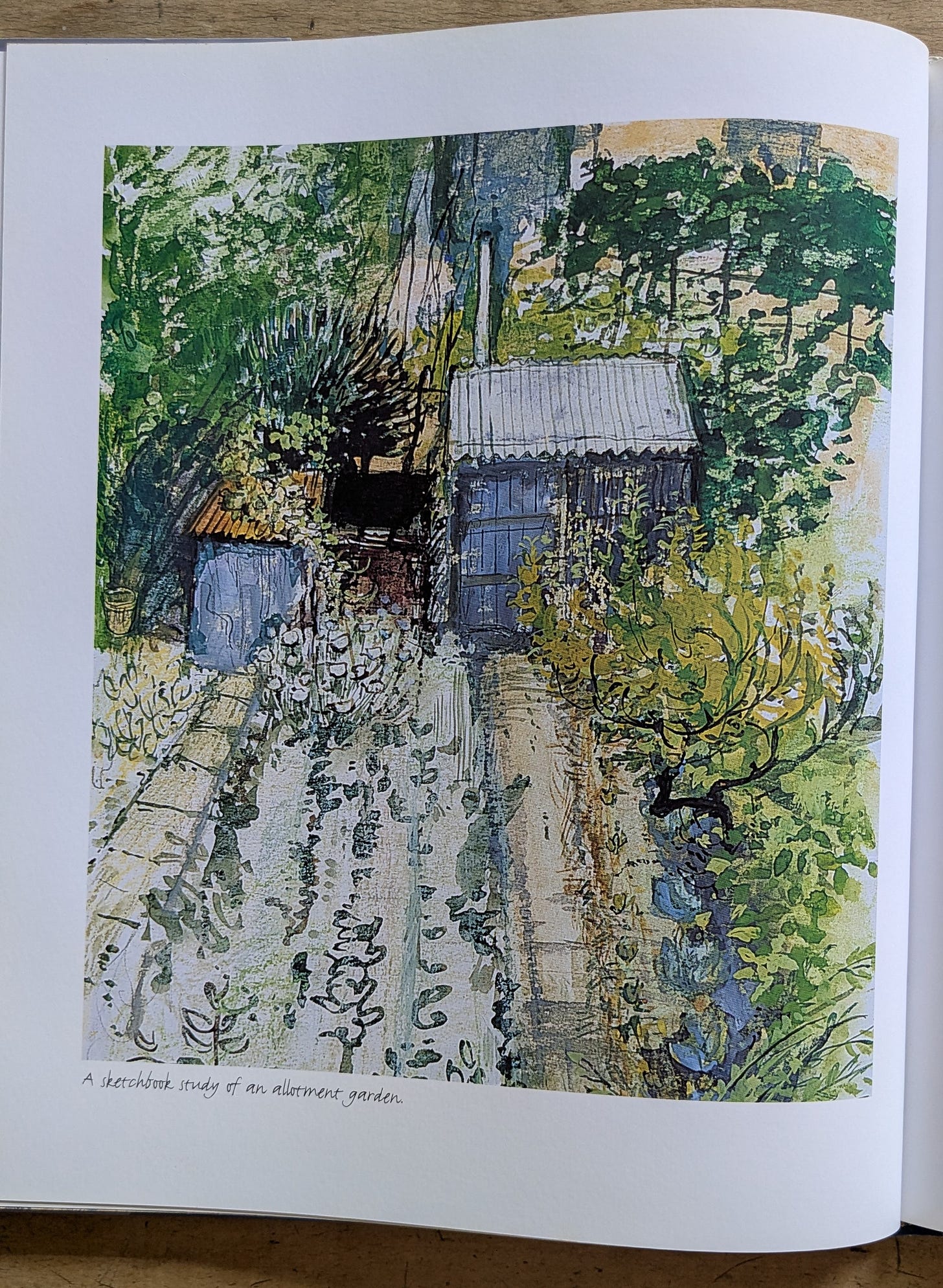

All of these observations, pages and pages of sketchbooks, fed back into her work, creating a storehouse of memories. While her interest centred on drawing children, her work demonstrated the importance of keeping a sketchbook, whatever your intrest or focus, observing and training the hand and eye. All of her illustrations were developed from these sketchbook studies.

Towards the end of her life she was asked her five year plan. The answer: “To do alot more in my sketchbook, weather permitting”. Free from the constraints of commissions, they allowed her “to make as many mistakes as you like, experiment with techniques, scribble over things, react to the moment”.

Never someone to be complacent in her work, she was inventive and experimental to the end. The thrill of it never left her, describing drawing as “the nearest thing I know to flying into the sun”.

What she loved to draw most was:

to sit under a tree in an Italian garden, with perhaps a glass of chianti at hand, trying to record dappled shade, geraniums rioting in pots, olive trees and a glimpse of an ochre washed, shuttered house beyond.

Her daughter, Clara, looking through her Italian sketches, said that this is where she hoped her mum was now. I hope she is too.

Something to watch

What Do Artists Do All Day from 2016 (here Part Two) shows a day in the life of Shirley Hughes. It is an enchanting film. I sat smiling as I watched it and the minutes slipped by far too quickly.

I also found this talk by her daughter, Clara Vulliamy. She takes us through her mother’s career and we see her work develop and her own distinctive style emerge, as well as revealing the process of her early book covers and picture books. Clara’s affection and pride in her mother is so evident, and very moving, and she gives us space to see the work in passages of silence, allowing us to take it all in.

Something to Read

Wendy Cope said of Hughes’ wonderful autobiography, “A Life Drawing: Recollections of an Illustrator”:

This, here, now, is what happiness is. Enjoy it.

And indeed I did, every page of it. Do read it, it is a beautiful, treasure of a book.

Shirley Hughes with the finished artwork for her 2020 book Dogger’s Christmas, her last novel published at the age of 92. Credit: Ed Vulliamy/The Observer

An illustration from Shirley Hughes' book Alfie Gets In First Note how she used the book’s gutter to separate the inside from the outside, as a split screen.

Sketchbook pages of children in Holland Park, rapidly created “almost pre-empting a movement a split second before your subject makes it”.

Judging a book by its cover

In Notes this week, a conversation developed about how book cover illustration has changed in recent years. I confess, an appealing cover is a huge pull to me purchasing a book, and always has been. I chose very often the bottle green Virago’s by their cover paintings, as much as the blurbs, and in recent weeks have been gazing endlessly at Penguin and Puffin covers from the 1960’s and 1970’s - beguiling lithographic images with spot colour, simple yet so evocative. But now so many fiction covers leave me cold. I don’t want to investigate further and read the book, and I am certain that I am missing out as a consequence. I would love to know your thoughts - what do you think of modern book design, have you ever chosen a book by its cover and, if so, which? I would love to know more.

Thank you for joining me this week. When there is such a great choice on here, I am so glad and grateful that you came along. If you enjoyed this piece, do press the heart, it really does helps. I shall be back again in a couple of weeks with the last, for a while, of my celebration of extraordinary illustrators. I look forward to seeing you then!

A “rough” of Alfie. You can see the exploratory pencil lines overidden by the energy of her pen marks that capture his eager movement.

And one last word from Shirley Hughes:

There is nothing more exciting than starting work; sharpening pencils and squeezing out my paints on to the palette. It is a moment of promise - Shirley Hughes

A Life Drawing is wonderful. I've also got a similar big hardback highly-illustrated memoir by Judith Kerr called Judith Kerr's Creatures. It's so interesting to see their work evolving over their lives, the layouts of their classic picture books, their record of childhood experience in Britain post war.

I enjoy seeing illustration celebrated as the art that it is.