The girl who should have been an artist*

Christine Kuhlenthal, Thomas Hardy and how Elizabeth Jane Howard is suddenly having a moment

Welcome to the fourth post in my series “Unheard Voices” about women artists who are now often overlooked and neglected. Once again, I have gone over the image limit for email and so it may be cut short in your usual email. You can read it either via Substack or press the“View the Entire Message” link to see it all. Thank you!

Christine Kuhlenthal has been on the periphery of my reading for some years. She was a friend of Dora Carrington, and later Tirzah Garwood, she worked in Roger Fry’s Omega workshops, she encouraged Ronald Blythe as a fledgling writer and was the wife of the painter John Nash. But it was while visiting the brilliant exhibition of Nash’s work in 2020, “The Landscape of Love and Solace” at the Towner Gallery, that I realised that this quiet friend of so many artistic figures, was a woman of interest in her own right.

Trying to find out more about her has been a circuitous task - she appears on the sidelines of others’ lives, the stories are frequently about them, and rarely about her, so I have had to try to gain a sense of her at a sideways angle.

Born on 11th January, 1895, Christine was the only child of Wilhelm Kuthlenthal, a German merchant chemist, and Scottish Ada Bustin. Her childhood was filled with art, music and culture, and Ronald Blythe compared her upbringing to that of Schlegels from “Howard’s End”, a home of the intellectual elite. She flourished creatively, becoming not only an artist of great promise, but also an accomplished pianist. He describes her as having an air of being ‘special’:

Whilst not beautiful, there was something about her presence, her voice, her movements particularly, which made her memorable…At first sight she looked more like someone from a ballet school rather than an art school.

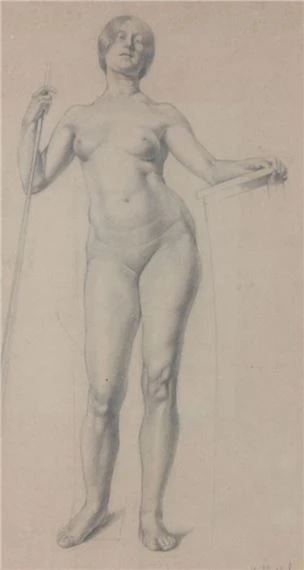

Christine Kuhlenthal- Pencil drawing of female nude, 1913, Winner of the Slade Figure Prize © Private Collection

She shone too at the Slade, winning the figure prize for drawing in 1913 and her work that remains from this period shows a strong sense of composition, clear draughtsmanship and narrative skill. In “The Picnic”, one of her final set pieces, we see Christine seated, with an apple on her head, alongside her friends Norah and Charlie. She is the focus of the painting, in vivid yellow, peering into the distance. Yet there is an uncertainty in her gaze. A photograph, taken by her friend Dora Carrington, making a preparatory study for the painting, shows her confidently in front of her easel, but it was a task that caused her great distress in spite of its successful outcome. Her eyesight was declining and she was finding it increasingly difficult to paint.

Christine Kuhlenthal at her easel ©The National Portrait Gallery, gift of Ronald Blythe

It is unclear how much she told her friends about her developing glaucoma, or of the constant, painful visits to Moorfields, but a letter to Carrington suggests that they knew little, who vents her frustration at her friend:

Do a good picture! I sometimes feel angry with you for a lack of energy about painting…but I don’t think you are an artist in the painting way. Excuse me for being so frank. Because if you were you couldn’t go back to it at odd times. You would have to live for it. No, I am not talking rot.

When Carrington discovered the truth three years later, she was distraught, no doubt painfully aware of her earlier criticism, and wrote a letter apologising for her “beastly” comments. Christine would not paint again.

The Picnic - Christine Kuhlenthal © the estate of Ronald Blythe

The Annunciation - Christine Kuhlenthal © the estate of Ronald Blythe, another set piece from her time at the Slade.

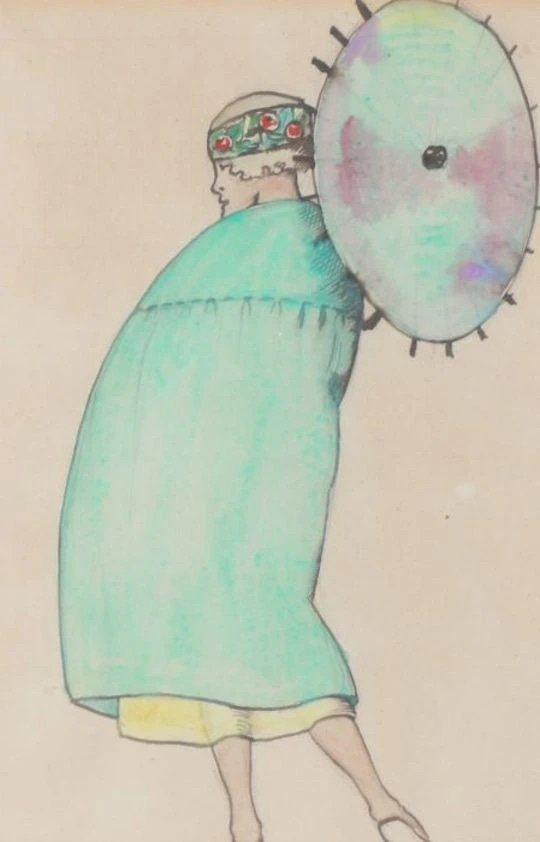

Christine Kuhlenthal - Lady with Parasol, watercolour and pencil Private Collection

And yet, the picture appears more complicated than this, as we shall see. During her time at the Slade, she met John Nash, the painter with whom she was to spend nearly sixty years of her life. They were engaged in 1915 and they pledged, that should John survive the First World War, their relationship would be “intimate and free”, and not exclude other loves. It would be a commitment, but not a bind. Their letters in those intervening fourteen months are tender and reflect the fragility of their future. She wrote:

I know dear you will be good to me in the way you mean. I will try to be good to you. We will never let the sun go down upon our wrath. I really (consistently) mean that darling and I don’t think I shall forget it all my life. Oh, I hope we get the chance to put our ideals into practice.

While waiting for him to return she taught at a girl’s school, organising dance classes and embroidering badges on to the uniforms. She worked too at Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops, with Dora Carrington, painting lampshades with “ferocious cubistical designs” and, as an skilled dressmaker, created “a green and yellow, and black and white and khaki check dress for Nina Hamnett”, as shown in Roger Fry’s painting below. It is a dress that I have long admired!

Nina Hamnett - Roger Fry © The Stanley and Audrey Burton Gallery, University of Leeds

A private view card probably designed by Duncan Grant for the opening exhibition at the Omega Workshops in 1913

© Henrietta Garnett.

Christine and John were married on the first of May, 1918, on John’s return from active service. With the outcome of the war still so uncertain, it was a simple, solemn affair, with his brother Paul as best man.

In the early years of their marriage John was doggedly determined to succeed as a fine artist, refusing to take commercial work, and though both their parents were concerned at his precarious choice of career, and their evident financial insecurity, Christine supported him completely. She continued to earn money with dressmaking and in March 1920, an advertisement exists for a show of her clothing, with a wood engraving by John Nash, at 9 Fitzroy Street, a short distance from the Omega Workshops.

John Nash and Christine Kuhlenthal © National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

In addition to this she ran affairs at home, organising the household and protecting John’s painting time, even liaising with galleries and framers on his behalf. John Lewis commented on her excellent organisational abilities, “she darned and patched clothes and concocted meals out of practically nothing” and daily she made bread, as John didn’t enjoy shop bought produce. All the while, Ronald Blythe notes, “she did this slavishly and with a certain wit.” There is certainly no hint of resentment and her role has to be viewed in the context of the time where such tasks were the norm for women.

Another of her roles, especially later in their marriage, was to go on “recces” finding places for John to paint. She travelled to Scotland, Wales and Cornwall seeking out spots that had both simple accommodation ( preferably a pub that served an evening meal) and suitable subject matter. The critic Allen Freer said that Christine had an inherent understanding of the form of the landscape:

Her response was in some respects more instinctive and intuitive than John’s - and she knew it. Which is why, perhaps, it was she who sought out the landscapes for him to paint.

While this may have been a practical use of her time, I confess this detail did make me baulk when I read of it, recognising the difficulty and time consuming nature of the task.

There is no question of her devoting time to renew her own art, all her efforts and energy were put towards enabling John to do so. Ronald Blythe insists that John wasn’t selfish in his endeavours, just singleminded, and that Christine, in doing all she did, was supporting him as the painter in their partnership.

Christine Kuhlenthal, 1919 © The National Portrait Gallery

She did, however, comment that, “One artist in the family is enough…” She acknowledged that had she continued this would have led to a less equable relationship. Andrew Lambirth attains that in doing all she did she was making herself “indispensable” in John’s life which was rooted in her “doubting her ability to hold her husband’s interest in the long term.” While this is uncomfortable to consider, there may be some truth in it.

This brings us to the nature of their relationship and their early declaration to be “free”, allowing them to have liaisons outside their marriage. While Christine certainly was involved in other relationships, John’s frequent affairs certainly caused her a great deal of pain. One affair , with a twenty four year old Ruskin student, “Fif” Dockar - Drysdale proved more of a threat than usual, and in November 1927 Christine wrote, “a new episode, supposed to be on truly platonc lines, is being started, but I have my doubt”. Sadly, she was proved right and Christine would go on to observe further affairs from the sidelines, with no intention of leaving him, wishing only for a “quiet life”.

The pattern of their marriage continued until tragedy struck. Following a series of miscarriages, their only son William, was born in 1931. In November, 1935, Christine dropped John to the station, and William sat next to her in the passenger seat. As they were travelling, the passenger door flung open and William slipped forwards on the shiny leather seat. She grabbed his coat, but she couldn’t hold him. He hit his head on a drain cover and never regained consciousness.

It is hard to comprehend the impact this must have had. We know that they slowly resumed the old pattern of the lives and that John filled his life with work. Christine longed for another child, but knew that as she was over forty, with the additional concern of John’s “episodes,”( her name for his affairs) made this unlikely to happen.

It is difficult not to feel condemning of Nash. Her sense of commitment and tireless support of his work, meant that any serious pursuit of her own talents was at best thwarted. From 1920 to 1975, the year before her death, she kept journals in exercise books, that are filled with sketches and drawings and lively description. Never intended for publication, they detail their lives. Blythe said they were a “haven” for her, “for the girl who should have been an artist, a musician or dancer”.* She had ambitions to be a writer, a talent John encouraged, writing a novella called “Miss Jenny”, but it was never published.

She had an enormous talent too for friendship. Ronald Blythe, who looked after the couple in later life, dedicated his first novel to her. She had encouraged him to leave his library post to be a full time writer and introduced him to local artistic circles to help forward his career. When Tirzah Garwood, wife of Eric Ravilious, was ill with breast cancer, it was Christine who found her a nursing home and ensured she was cared for.

Certainly, without Christine, John Nash would not have completed the body of work that he did, but it is difficult not to wonder at the cost to Christine’s own creative life. While her glaucoma would have contributed to her decision to cease painting, she still able to sew, write and made make drawings, so it was evidently a decision that she made for other reasons, perhaps to not upset John, as has been suggested, but it is impossible now to know. While finding out about her life, I often felt frustration, but also enormous admiration for a woman who lived with such grace and generosity.

John and Christine Nash At the Rising Sun, St Mawes, Cornwall, 1975 on a painting recce. © Tate.

Something to read

I felt slightly apprehensive returning to the writing of Elizabeth Jane Howard. I had loved her novels as a student (shockingly last read in 1984), and have since enjoyed her Cazalet Chronicles, but it is her early works that have meant the most to me. The Long View, my first reread, is the portrait of a marriage told backwards in time. It is acutely observed, beautifully written and demonstrates that Howard really should have greater recognition. Strangely, while writing this, serendipitously a news item appeared about her niece continuing the Cazalet books , I found Susan Hill has written a fascinating post about Howard here, that India Knight has written of her “Devils on Horseback” and that Laura Thompson has released an archive post too. She was also Hilary Mantel’s favourite writer. Hopefully a renaissance is in the offing.

The home of Elizabeth Jane Howard, in the market town of Bungay, where I visited at the weekend

My much loved, battered copy

Something to listen to

Her wonderful saga , dramatised on radio, is available on Spotify (I have it on the original CD’s!) and it is the perfect listen for winter evenings, or in the studio. You can also hear her discussing her chilling late novel “Falling” here and on Desert Island Discs.

Something to watch

Thomas Hardy - A Haunted Man I should issue a warning with this choice, as it is not a comfortable viewing, but it is a remarkable programme. Based on the biography by Robert Gittings, and first broadcast in 1978, it charts the marriage of Hardy and his first wife, Emma, played by Cyril Luckham and Billie Whitelaw. It was a deeply unhappy marriage, and they lived quite separate lives, Emma occupying the attics of Max Gate, their home. She decried in a letter of 1894 that Hardy "understands only the women he invents - the others not at all." Following her death, and after marrying his second wife Florence, Hardy wrote a series of poems, full of love and regret, for Emma. These are read beautifully here by Luckham and a must if you, like me, love Hardy’s work.

And for those fellow Virago lovers, I came across this, which has Carmen Callil talking about her favourite book choices .

Thank you very much for your company here and for taking the time to read this. I would love to hear your thoughts about Christine Kuhlenthal in the comments, or indeed about anything else that you have read here - I always love to hear from you! If you enjoyed this piece, don’t forget to press the “Heart” to help my post to be seen, it makes such a difference. I shall look forward to seeing you again in a couple of weeks.

Further Reading

First Friends - Ronald Blythe

Outsiders: A Book of Garden Friends - Ronald Blythe

Carrington’s Letters: Her Art, Her Loves, Her Friendships - Anne Chisholm

John Nash: The Landscape of Love and Solace - Andy Friend

John Nash: Artist and Countryman - Andrew Lambirth

Great post, Deborah! I watched the Hardy programme - yes it was sad, and the second wife must have suffered terribly. I'm just thinking about reading EJH. I've only ever read After Julius, a long time ago, and I think I'm the only woman in the UK who hasn't read the Cazalet books.

PS has anyone written a book …The Women of the Slade because I keep tripping over them and wanting to know more. Most recently Dod Procter whose mother Eunice Shaw (née Richards)went there.