The Quiet Moon

The art of Mary Potter (1900 - 1981), the menace of Moon Eyes and now we are six-ty

The Rising Moon, Oil on canvas , 45.7 x 76.3cm, Mary Potter, 1942 © Ferens Art Gallery. Image credit: Ferens Art Gallery

Like all proper artists she teaches us to see more, and differently. Myfanwy Piper on Mary Potter

When I was a student I bought a birthday card in the Tate Gallery, but the card never reached its recipient, replaced by another, as I couldn’t bear to let it go, and forty years on, I have it still. It pictured the painting above, by the artist Mary Potter, of the pale moon lighting the gateway to a cottage glimpsed down a drive, edged with beech trees, clinging on to their last leaves. Above the crumbling brick wall, holding the bare stems of an unknown climber, a church tower can just be seen. The sky is flushed with the soft pink of midwinter, the same hue of the driveway and mortar of the bricks. The tonal range is slight, but perfectly harmonious, and there is a sense of quietude, both in the subject and colour palette, that holds us.

I thought it the perfect choice for the beginning of a new year, when the first full moon, is called the Quiet Moon. For the ancient Celts it symbolised the hush and chill of the new year, marking that the hardest days have passed and the light is returning. It was also felt to be the time when our attention shifts to renewal and a gathering of energy.

As I looked into the life of Mary Potter, it seemed appropriate too, as although she gained some success through her life, it was when she was in her sixties that her career flourished in an outpouring of late creative energy.

She was born Marian Anderson Attenborough, in Beckenham, Kent in 1900, to prosperous, professional parents. One of her childhood friends was the children’s writer Enid Blyton with whom she created a group called the “Mauve Merriments”, performing in white ruffles and black pompoms, with Mary taking the leading roles, and Enid accompanying on the piano. Like many of the artists I have covered, Mary was prodigiously accomplished, but she upset her parents by chosing drawing above her other talents, much to their dismay. She set upon going to Beckenham Art School, defying their wishes to complete her education, to then go on to the Slade in 1918.

The artist Mary Potter

Here Mary became “Att” and, under the tutelage of Henry Tonks, won 7 prizes, including the Slade Scholarship in 1919 and the First Prize for painting in 1921. While she benefitted from Tonks’ drawing discipline, she did not follow his advice uncritically. Early on, she determined to work in pale tones, showing courage and confidence in her own instincts, believing herself “to be the best judge of her work”.

Tonks clearly admired her determined approach and on leaving the Slade, arranged for a number of portrait commissions, noting her ability to catch a likeness. Though he warned her, “You must never get married. You have to give up everything”. When he discovered that she had married the writer, Stephen Potter, author of the hugely popular “Gamesmanship”, he despaired. “It is a tragedy. Their work always deteriorates when they get married”.

But it seems he had underestimated her determination. While she could easily have pursued a career in portraiture, it was not her chosen path. She felt she was working “on automatic” and it was hindering her progress as an artist. Although we know that she worked consistently since leaving the Slade, until her marriage in 1927, only 5 paintings from this period remain. There may be others, but as she frequently didn’t sign her work, they are difficult to attribute.

An unexpected discovery while learning about her, was her contribution to the “Aero” Rowntree chocolate campaign which ran from 1950 - 1957. Keen to present their product as “Different” they chose to commission key artists of the day to paint oil portraits of unknown young women. Mary Potter was the only female artist chosen. Sadly her contribution has been lost, though her subject recalls,"Mary explained that she wanted me to wear my old duffle coat and woolly hat with a bobble, I said 'Can't I wear something pretty and less dreary?' But Mary was firm, explaining that Aero is different, so the whole point is that you have to be different". What made me smile were the words, “Mary was firm”, a trait that repeats throughout her story. Below is one of the images used in the campaign, all of a similar style, and one can understand, in view of Mary’s painting as a whole, why made the decision to forge her own way.

Very little of Mary’s correspondence or writing survives, especially from the years of her marriage. She was a very private person and the records of her life that remain come from the reminiscences of those in her circle. Her husband, Stephen, left fragments of autobiography and I loved this snippet that captures her working:

Sitting on a wall, with a watercolour block on her knees she would screw up her forehead into a maze of lines…It was a drizzling-looking sky, the day and the landscape was as dull as lead. “What is that, the shadow?” Att might ask me, meaning “what colour?” “Just dingy dark?” “There’s a lot of purple in it”, she corrected me. “That’s the funny thing. And specks of umber”.

Here we see not only her love of painting the subtleties of English weather, but also her ability to pinpoint colour precisely. Later in their marriage, her son remembers a decorator’s exasperation when asked to come up with a hue that matched, “the pale daffodils at the end of the lawn when the sun shines through them from the other side”. Apparently, he came up with a blend that was almost right!

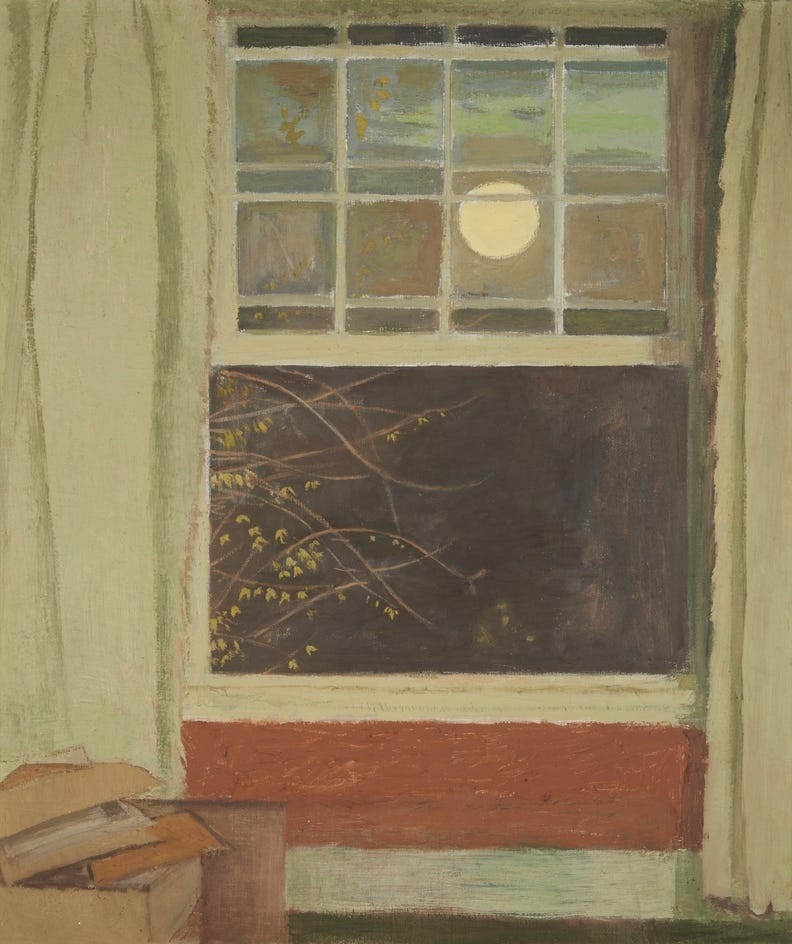

The Window, Chiswick, Oil on canvas, 1929, 76.4 x W 55.2 cm © estate of Mary Potter. All rights reserved, DACS 2024. Image credit: Tate

The early work above is a favourite of the writer Penelope Lively, who found her work a relief among “the current vogue for vibrant colours” which she saw in the 1950’s. Painted while living in cramped rental conditions, Mary, as ever, refused to allow such constraints to inhibit her work. Her son describes her as having, “remarkable powers of concentration, and there was little to distract her once she had set up her easel and made a start”. During her 12 years at Chiswick, she produced over 200 oils and many watercolours, her chosen objects, often framed by the window, would be alternated in taking centre stage as repeating motifs. The tonal unity prefigures her later work, the dull salmon of the book is picked up in the hedge and in the rooftops beyond. But she also has the capacity to capture moments when little happens. Lively describes this scene as one, “which has been painted several times over, and becomes something memorable and arresting”.

In 1951, Mary and Stephen move to the Red House in Aldeburgh, and here began a nurturing friendship that was to prove the catalyst of her late blossoming. Stephen was already acquainted with Benjamin Britten, having worked with him on a BBC production of “Albert Herring”, but now it was with Mary that the connection grew. Britten’s partner, Peter Pears, was a collector of contempory art and, on discovering her work, a painting was soon purchased.

Open Window by Moonlight (Night Window 1955, Oil on canvas)© estate of Mary Potter. All rights reserved, DACS 2024. Image credit: Britten Pears Arts

Mary and Stephen’s marriage ended in 1954 when Stephen left her for the writer Heather Jenner. At first, Stephen continued to visit at weekends, unable to reliquish his Aldeburgh life, but Mary understandably found this a painful intrusion, and it prevented her from making a fresh start. She struggled financially too, taking in lodgers when his payments became sporadic.

Ben and Peter, keen to support her, took her on a trip to Switzerland and she returned with a clutch of watercolours. While such dramatic landscapes were far from her usual quiet subjects, these transmuted on returning home into a softer form, and sold well. A further outcome of the trip was Britten’s “Alpine Suite” that he dedicated to Mary with the inscription, “…a tiny memento of a perilous journey, the results of which have made the world so much richer (and I mean visually!)”

When Mary realised that her home was now too big for her, and was unable to find an alterntive, Britten came up with a solution. Knowing that she had regretted leaving the Red House, he offered to build her a bungalow, with studio attached, in the grounds of his home, a generous gift that arrived just as she received the offer of a major exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery.

Carnations, oil on canvas, 1950, 84.4 x 61.4 cm © estate of Mary Potter. All rights reserved, DACS 2024. Image credit: Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums

The director of the gallery, Bryan Robertson became the second of her great advocates. At the age of 62, this was delightfully unexpected and the confidence placed in her encouraged her to create larger, more experimental works. Robertson wrote to her:

My own feeling, quite simply, is that you have never had a real chance with your work. You have only been able to exhibit it inside a very restricted and dull framework…I believe, absolutely that your work has an immense potentiality which is not yet realised. You are eminently capable of realising it and I look forward to the time when your painting really takes off.

This, in combination with a custom built studio, about which she declared, “Thank heaven I shall have a proper large studio window!”, along with the space, freedom and time to produce more expansive work. Her work was distilled, her chalky mat paint thinned and the horizon line often lost altogether, but the soft grey palette remained. In these late works, Mary Potter rose triumphantly to the challenge finally receiving the acclaim she deserved.

The exhibition was seen by over five thousand visitors in London and a further seven thousand when it was shown in Sheffield. While the work was lauded, some critics felt the cavernous space of the Whitechapel unsuited for her muted work, and many of the larger works were unsold.

But this was not the end, but a first step. Kenneth Clarke, critic and founder - patron of the New Art Centre offered her an alternative, more intimate venue which began a long and happy association, giving her biennial solo exhibitions until her death eleven years later. They were so assured of her worth that they bought up any work that they could find to resell at a higher value, allowed each exhibition to run for several weeks and painted the gallery walls in whatever colour she felt best complemented her work.

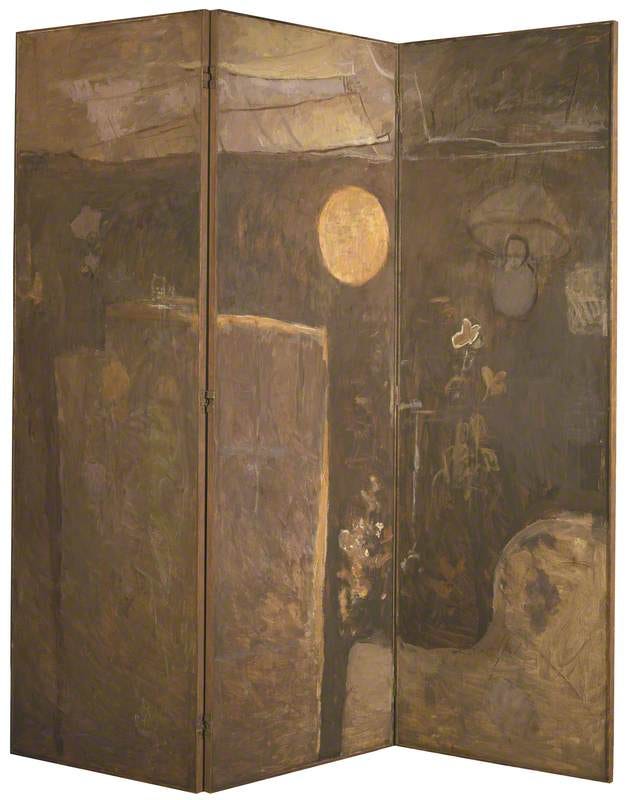

Night and Day, a painted screen© estate of Mary Potter. This is indicative of her late, pared down style and was exhibited in her last exhibition All rights reserved, DACS 2024. Image credit: Manchester Art Gallery

Mary Potter continued to work until the very end of her life. When unable to stand for sustained periods, she sat at her easel in a wheelchair. In her last weeks, the novelist Rosamund Lehmann visited her several times, and Mary made sketches of her, that although “blurred” are clearly recognisable portraits. Her conviction and dedication to her work never failed. She told the young artist Tim Fargher that artists, “should never let any real or imagined difficulties stop them from pressing ahead” and when asked what her advice to those starting out, she said:

Draw all the time, anything and everything, and you will find things begin to happen. The only answer is to keep doing it - particularly when you are not in the mood, and your potentialities will develop.

I can think of no wiser counsel.

This Christmas I turned sixty. All year I have been preoccupied with this forthcoming birthday and I was filled with dread at its arrival. Now it is here, I feel nothing but relief and a sense of freedom stretched before me. Reading about Mary Potter, her late flowering, that began at the age of 62, was not the subject I intended to cover and I did a sudden about turn which proved to be a very happy discovery.

Thank you very much for all your support here, it means a great deal to me and may I wish you all a very happy new year.

If you liked this post, please press the “Heart” and do consider taking out a paid subscription to allow me to continue here.

The Swans c.1930 Oil on canvas, 80.8 x 70.1cm © estate of Mary Potter. All rights reserved, DACS 2024. Image credit: Williamson Art Gallery & Museum

Still Life Oil on canvas, 1959 © estate of Mary Potter. All rights reserved, DACS 2024. Image credit: Manchester Art Gallery

Something to Read

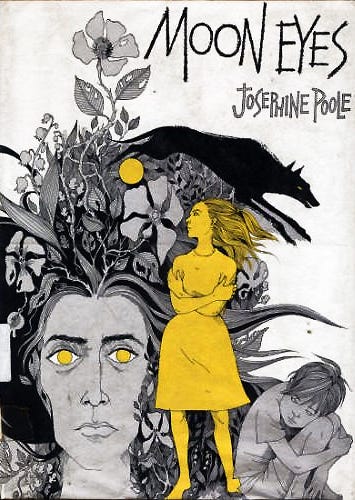

Moon Eyes - Josephine Poole

First we’ll wait, then we’ll whistle, then we’ll dance together…

Does anyone remember this? I read it a class book at the age of eleven and then asked to take it home so that I could read it again. Josephine Poole is little known now, but if you love “The Dark is Rising” sequence or Alan Garner, then I am certain you will be as captivated by this as I was. It is her use of language and sense of menace that has stayed with me, as much as the sinister figure of Rhoda Cantrip and her wolf-like companion, Moon Eyes. The story begins with this, “Moon Eyes is based on an extraordinarily vivid and frightening dream. I dreamt I was in a garden, in the shadow of a house. As I walked there, the words “First we’ll wait, then we’ll whistle, then we’ll dance together” came with supernatural menace into my sleeping mind - and then I woke up. The disconcerting thing was finding the actual house, and the garden, some months after my dream…” I suspect that is enough to tempt you…

Swans at Cley on the Winter Solstice, caught just as dusking was falling and I was about to head home

Another year, and cause for meditation. What better than to sit in the new armchair and to watch the seagulls circling. And to think. Not a resolution in sight. Instead a kind of freedom. From “Stour Seasons”, Ronald Blythe

And to end …

A favourite poem that captures the wonder of gazing up at the moon.

Full Moon and Little Frieda

A cool small evening shrunk to a dog bark and the clank of a bucket -

And you listening.

A spider's web, tense for the dew's touch.

A pail lifted, still and brimming - mirror

To tempt a first star to a tremor.

Cows are going home in the lane there, looping the hedges with their warm

wreaths of breath -

A dark river of blood, many boulders,

Balancing unspilled milk.

'Moon!' you cry suddenly, 'Moon! Moon!'

The moon has stepped back like an artist gazing amazed at a work

That points at him amazed.

Ted Hughes

Further Reading

The Time by the Sea: Aldeburgh 1955 - 1958, Ronald Blythe, Faber and Faber, 2013

Writing on the Wall, Edited by Judith Collins and Elsbeth Lindner, 1991

A Broad Canvas, Ian Collins, Parke Sutton Publishing, 1990

The Unquiet Landscape, Christopher Neve, Faber and Faber, 1990

The Quiet Moon - Kevin Parr, The History Press, 2023

Mary Potter: A Life in Painting, Julian Potter, Scolar Press, 1998

Voyaging Out: British Women Artists from Suffrage to the Sixties, Carolyn Trant, Thames and Hudson, 2019

I knew Mary well during the last 15 years of her life. This piece captures her perfectly. I had two of her big oils which, alas, I had to sell when I was very hard up. I miss them. I miss Mary. Thank you for what you've written which has brought back so many happy memories

Happy 60th Birthday! I turned 60 in May and it's been unexpectedly liberating and opened up avenues I wouldn't have anticipated. It's felt like something biological happens and I've read about others saying the same - a real now or never philosophy, and a sense of it's never too late. I wish you a wonderful year full of opportunities.