A Portrait of a Marriage

Mary Fedden, her life with Julian Trevelyan and her late flourishing

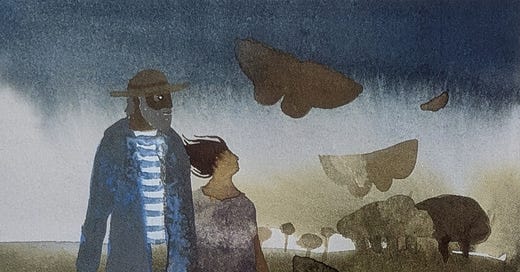

Mary and Julian, gouache, 1995, 40.6cm x 44.5cm © Sotheby’s picture library

How many artists can you say paint happiness? She does. And it is needed.1

I was delighted that you shared my love of the work of Jean Cook and was as affected by her life as I was. This week, I determined to find a counterbalance to her story, one that showed a relationship of two artists who nurtured and supported each other and who flourished in each other’s company. I confess that this was a much more difficult task than I anticipated, but happily I came upon Mary Fedden and Julian Trevelyan, but as in all good stories, things turn out to be slightly more complicated.

I have long loved the work of Mary Fedden (1915 - 2012). Her work is joyful, vibrant and with enough quirkiness to remain on the right side of charming, though its appeal has brought out an unattractive snobbery in some critics ( but we shall cast aside such a lack of generosity for this piece.)

At school painting was the one thing I ever wanted to do…I’d never thought of doing anything but painting. Mary Fedden

Mary was from an affluent family, her father from a long line of sugar merchants, and at 11 was sent to Badminton, an academic boarding school. She hated it. The only salve was her art mistress, Monica Young, a former student of the Slade, who made life there ‘bearable’. She determined to leave at 16 to go to art school and though her parents finally acquiesced, they insisted that she remain in Bristol. Thankfully, Monica Young came to her rescue, taking it upon herself to visit her parents and persuade them to the contrary - she was not going to allow her prize pupil to go anywhere other than the Slade. To Mary’s great relief, they agreed and she set off to London, at the age of 17, to experience her first taste of freedom.

She studied there for four years, but later downplayed the impact it had on her work. She found the emphasis on drawing from the cast ‘boring’ and the subdued colour palette unappealing. She said, ‘a little mud added to your orange and your red were…tasteful’. Though Stanley Spencer was the guiding light at the Slade, she aligned herself instead to Vladimir Polunin, the Russian stage designer, who had worked for the Ballets Russes, and whose guidance injected colour and pattern into Mary’s work.

Another figure at the Slade, however, was to prove far more significant. Looking down from the studio window one day, she caught sight of a ‘wonderful’ 6ft 4 figure walking with Polunin, and she asked the college porter, Connell, who it was. “Oh, that is Julian Trevelyan.” Mary declared, “I am going to marry him!” “ Bad luck, old girl, he’s just got married”, to which she sanguinely replied, “Oh well, I’m only 20, never mind”. 2But, it seemed, fate had other ideas.

On leaving art school, she reluctantly returned to her parents’ home in Bristol, taking on portrait commissions to supplement her income (at which she was not very successful) and taught at two local art schools. But with the advent of the Second World War, she stopped painting altogether, becoming a land girl, throwing herself at whatever unpleasant task the farmer demanded of her. Mary, with characteristic determination, won him over and alleviated the boredom by learning poetry as she ploughed.

A cartoon by Mary Fedden for “The Land Girl” magazine entitled, “Popular Misconceptions” revealing the reality of working on the land

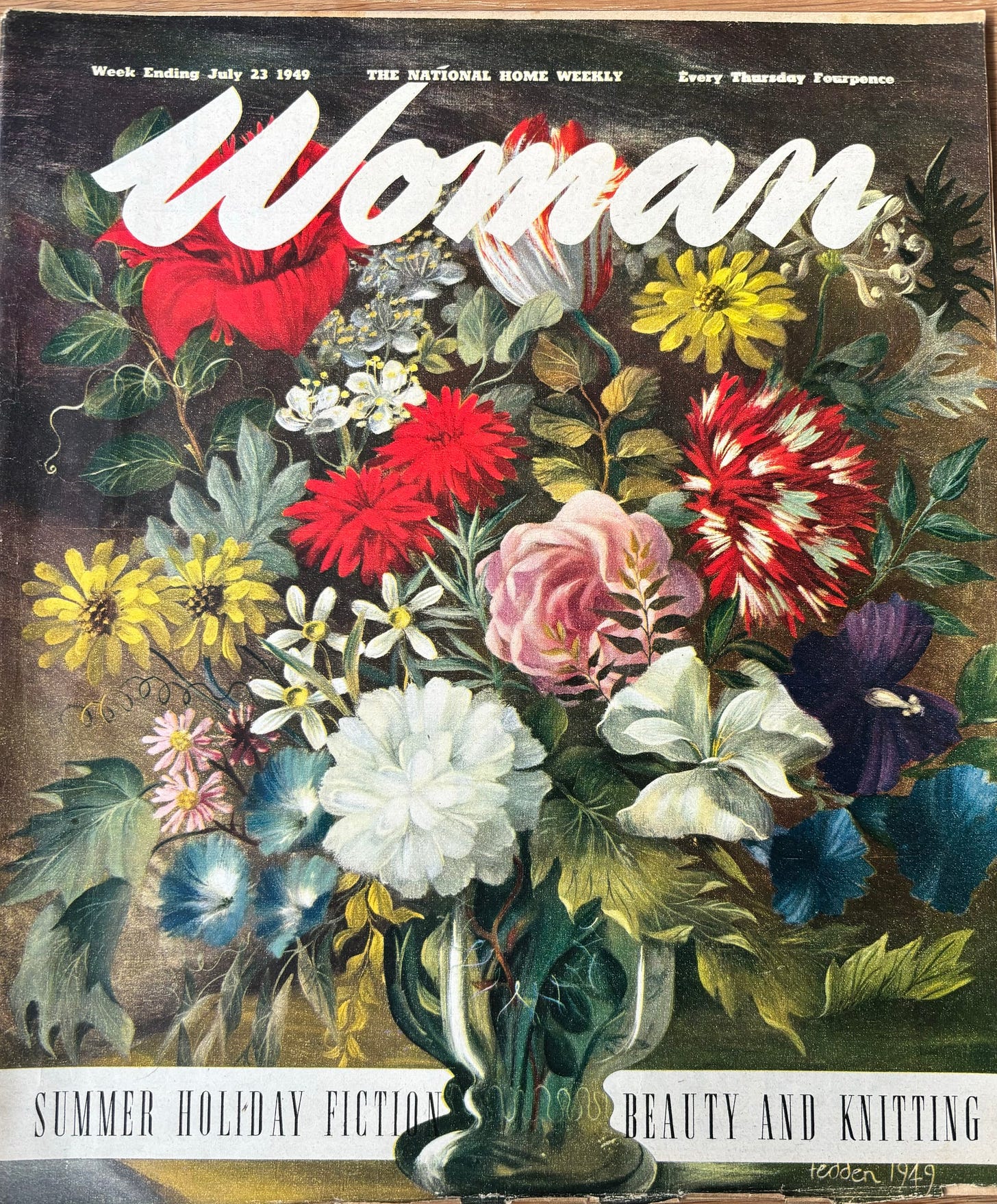

When the war ended, she began painting in earnest once again. In 1947 she had her first solo exhibition at The Mansard Gallery, which lay within the influential store Heal’s, and was the launchpad for many young female artists at the time, including the sculptor Elisabeth Frink and the textile designer Enid Marx. Mary’s exhibited still lives and flower paintings were spotted by the editor of “Woman” magazine, who not only bought a painting, but commissioned her to produce a cover eight times a year. This lucrative project gave her the means to focus full time on painting.

An example of Mary Fedden’s covers for “Woman” magazine, from July 23, 1949

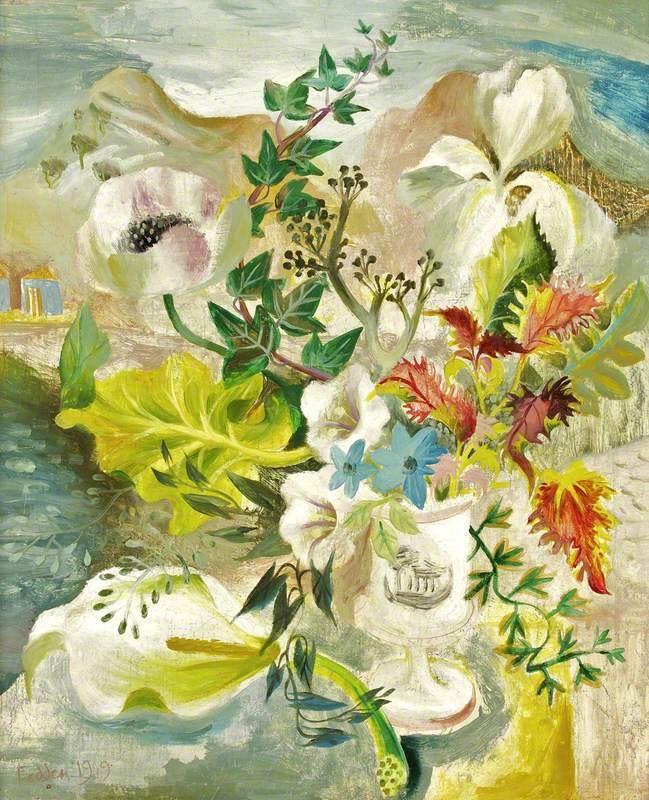

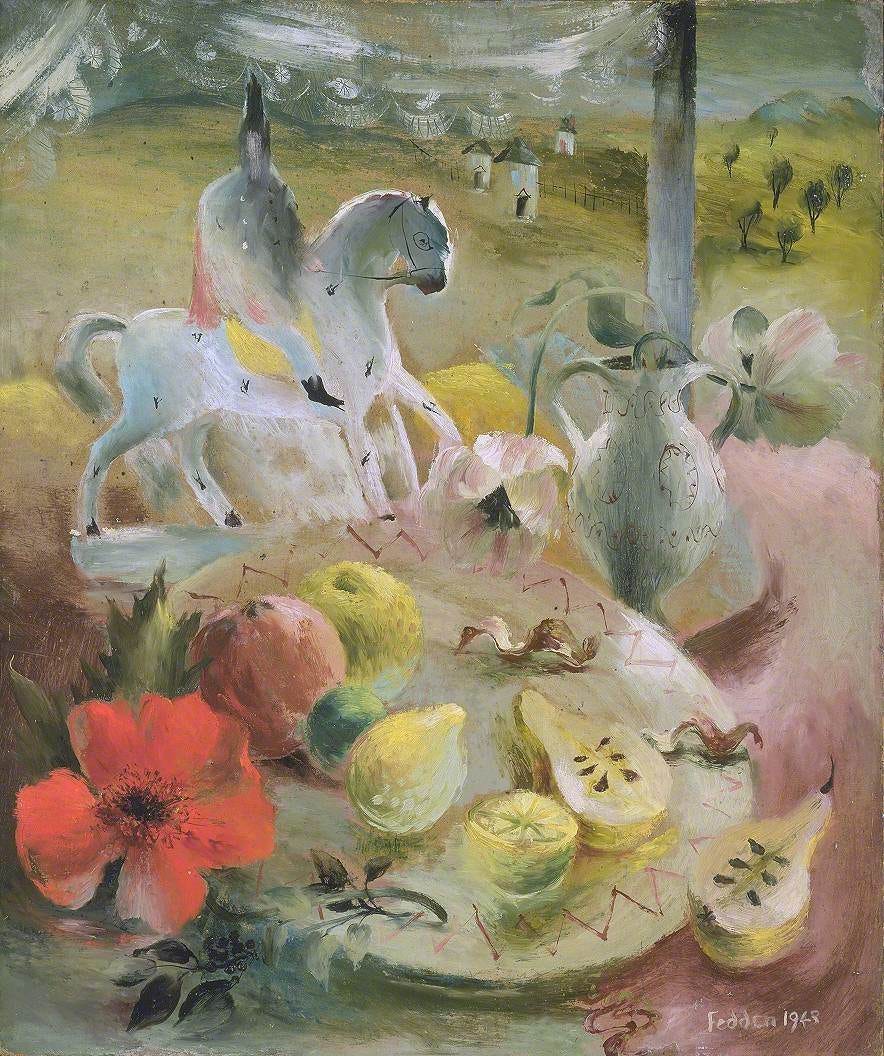

Her paintings created during the 1940’s are very much of the period, but in them we see the seeds of her later work: the beloved objects, next to the quotidian, with a strange landscape beyond. Later in life she came to consider them, “too romantic, old-fashioned, and not very original”, but this was to change with the arrival of Julian in her life.

Sicilian Flowers, 1949, oil on canvas, 59cm x 49cm © the estate of Mary Fedden / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives

The Staffordshire Horse, 1948, oil on canvas, 76.3 x 64.3 cm© the estate of Mary Fedden / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Tate

She had become friends with him and his wife, Ursula, since leaving the Slade and was shocked to discover in 1948, that Ursula had left him. Mary called her, and it was suggested that as Julian was so low, that he go with Mary and a friend on a planned a trip to Sicily. They travelled in Julian’s open topped Hillman across war torn Europe, constantly breaking down and getting punctures. The journey took two weeks and, by the end of it, Julian and Mary were in love.

'It was absolutely magical. It was the most wonderful thing that ever happened to me ... It was marvellous. And Julian was so happy. And so was I!'3

On returning to England two months later, Mary moved into his studio home in Durham Wharf. In his autobiography, “Indigo Days”, which ends with this new beginning in his life, he declared, “The Wharf boasts a new mistress and in the studio there are two easels instead of one”. Their home consisted of a bed sitting room, a studio and a printing room. On her arrival, making her mark, Mary painted the walls white and put in wooden floors and together they painted side by side for the next forty years.

Portrait of Julian Trevelyan, 1955; oil on canvas 147 by 60cm Painted four years after they married, this intimate , striking portrait is an image of contentment, with one of their cats curled up in his lap.

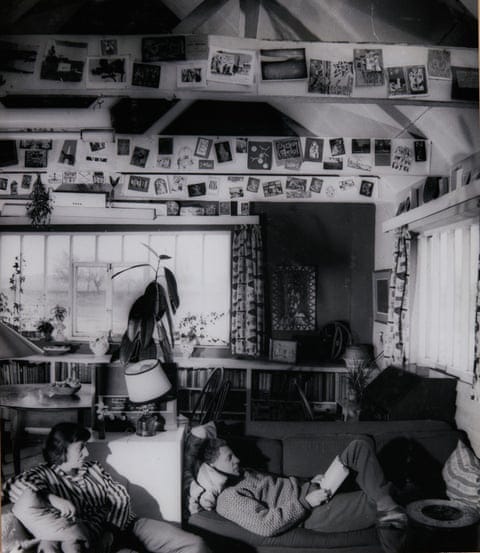

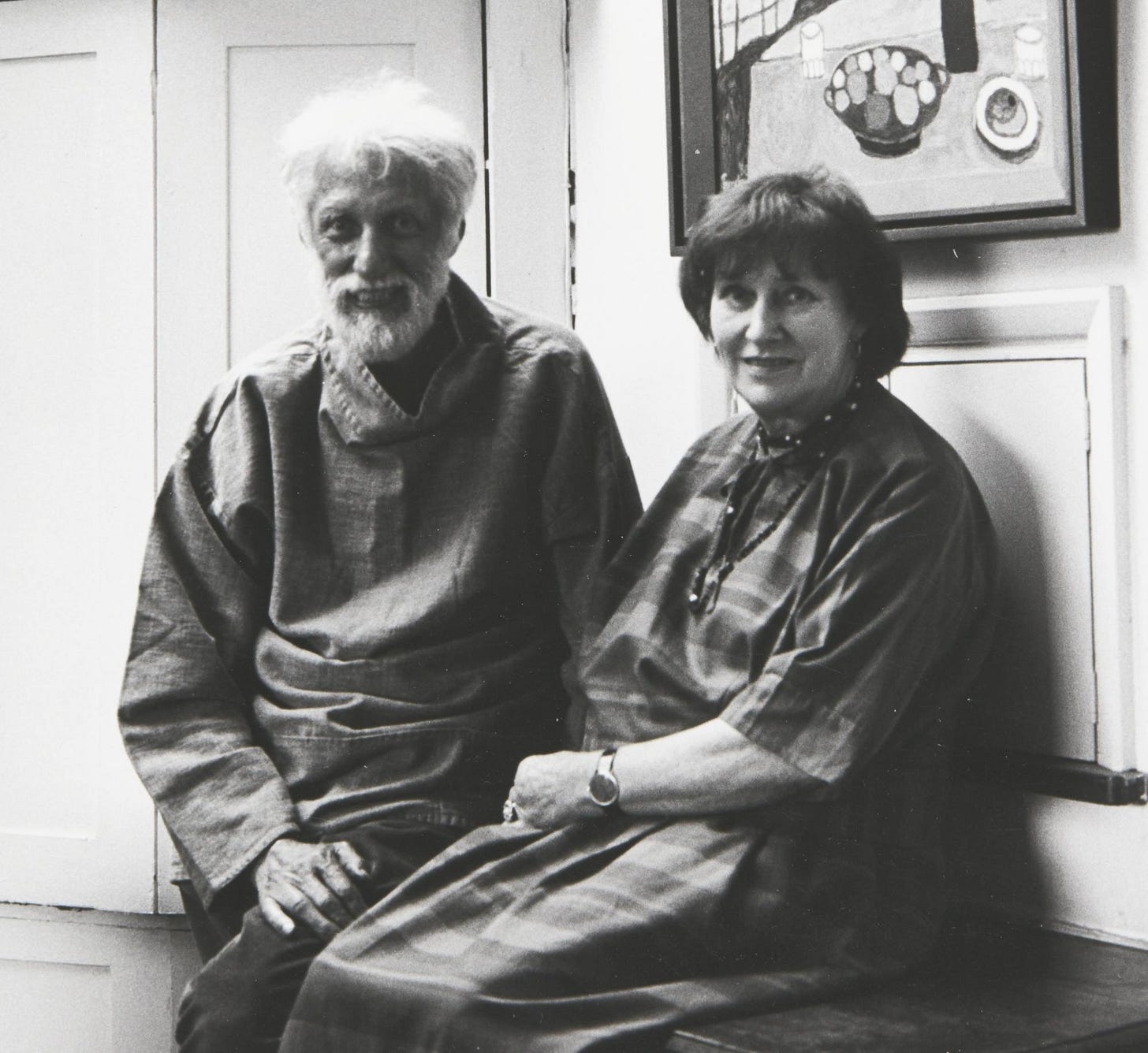

Mary Fedden and Julian Trevelyan in their home at Durham Wharf. Photograph: Sotheby's

Until this point, Mary’s work had lacked focus and confidence, but Julian recognised the direction needed. He felt her work was too “literal” and he told her, “You’ve got much more to your painting that what you are doing. You are not using your imagination”. He asserted that she needed to use her “mind” and not just her “eye”. It was noted by others that he “criticised her work most mercilessly” 4 yet rather than resenting this forthright approach, she trusted in his guidance and followed what he suggested. She later said, “When I went to live with Julian, it was the start of my painting life”. Certainly her work was revolutionised and during the 1950’s there is a paring down of her style, and though her subject remained the same, through his direction she found her “originality”.

Durham Wharf, by Julian Trevelyan, showing Julian and Mary tending their garden. Photograph: Sotheby's

Eyot Gardens (The Black Striped Jug) , oil on canvas, 1957, 79cm x 45cm © the estate of Mary Fedden / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: RWA (Royal West of England Academy)

As a painter, to have such a firm, objective opinion about one’s work can be of enormous value, but to have it guided to such a extent, does present a degree of unease. Certainly, critics have alluded to this. A particular incident troubles me as an example of his exerting influence. While out for a picnic, he found at the bottom of the basket, a tube of Prussian blue paint. Mary had no idea how it got there, but Julian grabbed it and threw it as far as he could. Mary says, “I’ve never bought a tube of Prussian Blue since. It isn’t a good colour”. It is clearly recalled with good humour, and she obviously took his controlling tendency in her stride. Interestingly, when in turn she offered advice on his work, he was less than gracious, he would “refuse and then whine”, but later she would note that her suggestion had been executed - though only when she was out of range!

Mary Fedden on the wall at Durham Wharf. Photograph courtesy of the Durham Wharf Archive

Red Still LIfe, 1967, oil on canvas, 1101.9cm x 132cm, © the estate of Mary Fedden

Of course, two egos rubbing along side by side can’t have been easy and Mary’s acceptance, and gratitude, for his support is not in doubt. In spite of their working proximity, their work remained distinct. In addition to their studio life, Julian taught etching, and Mary painting, at the Royal College of Art and both were held in high esteem as teachers. She was the first woman to be accepted as a painting tutor there, no mean feat when artists such as Pauline Boty, were finding it impossible to even gain a foothold as a student. Among her pupils were David Hockney, R J Kitaj and Patrick Caulfield and, though lecturers were encouraged to be working artists in their own right, Mary’s work did not sell well and Julian was far more financially successful. This, however, in her later life was to change completely.

In 1988, Julian suddenly became ill and died a few days later of heart failure. He had suffered a serious bout of pneumonia a couple of years earlier and had never fully recovered. Mary had tended to him tirelessly and, though bereft at the loss, she remained outwardly brave and friends rallied around her.

Julian’s last commissioned painting was of Strawberry Hill, by the collector John Iddon. Mary found she couldn’t bear to part with it and offered to create a painting of her own as an alternative. Iddon, knowing little of her work, agreed and the two paintings are shown below. Julian focuses on the architectural idiosyncracies in bold colour, whereas Mary uses the building as a theatrical backdrop. In the foreground, harlequin dancers scatter the evening light with sparklers and behind them a young girl wearing a pale pink evening dress, runs, her hair lifted by the breeze. It is a beautiful and mysterious painting.

Strawberry Hill, oil on canvas, 76cm x 61cm ©Estate of Julian Trevelyan

Masque at Strawberry Hill, Oil on canvas, 76cm x 61cm

In the months following his death, Christopher Andreae notes that his “sad departure could hardly be called a beginning, but it certainly wasn’t an ending”.5 Mary moved into Julian’s studio next door and his printing press was placed in her smaller studio. Rather than slowing down, she was now able to focus completely on painting, and her work flourished. Friends commented that she finally “emerged from his shadow” 6and that now it was only her own opinion that mattered.

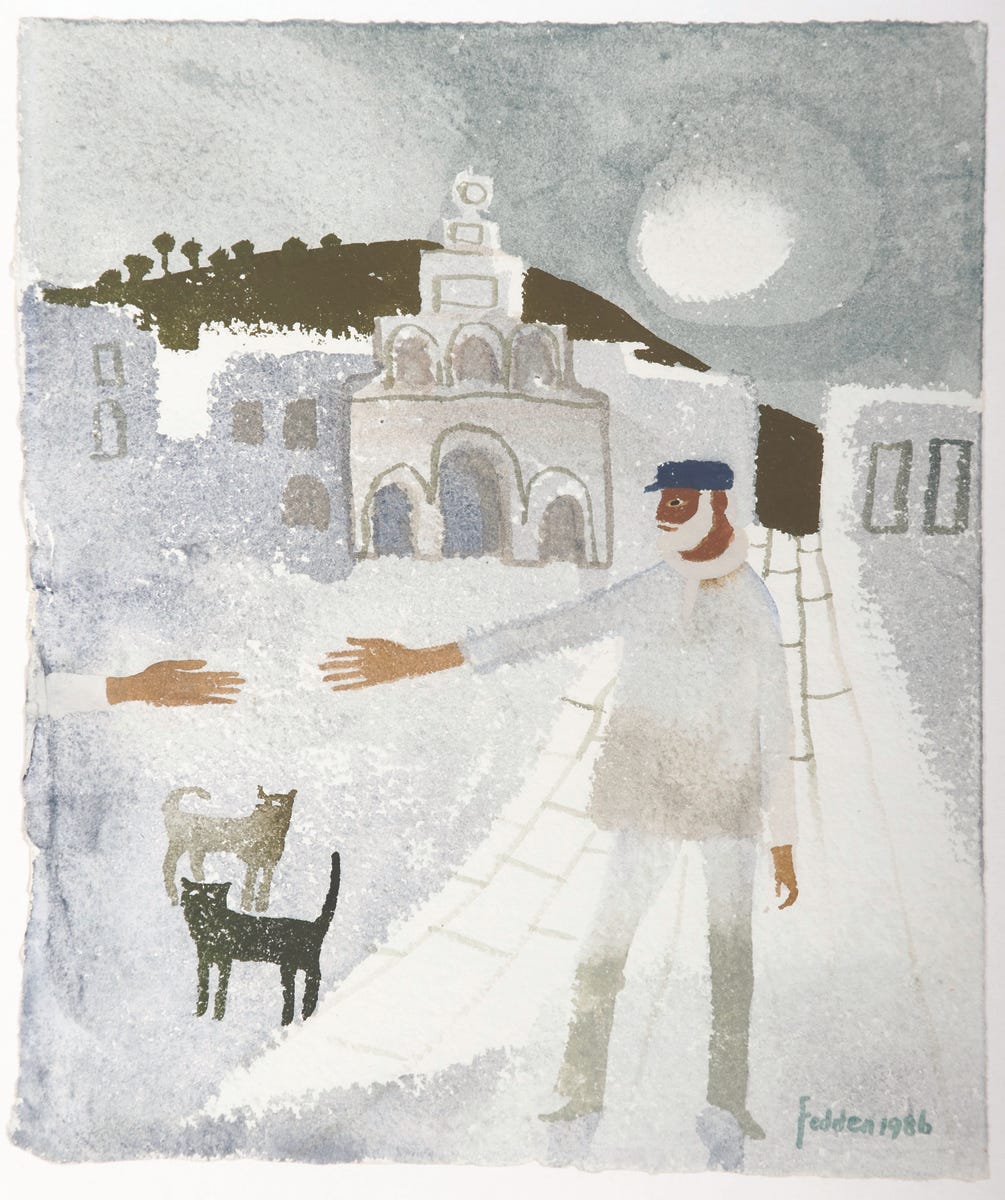

Julian, watercolour and gouache, 1986, 22.2 x 18.3 cm © the estate of Mary Fedden / Bridgeman Images

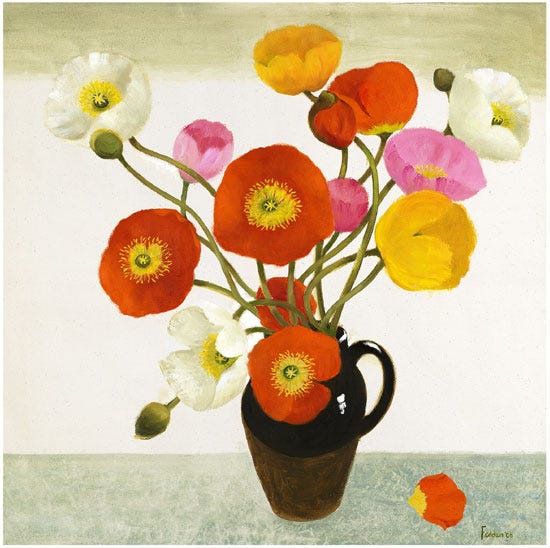

The style of her painting shifted too. It was not a conscious change, but a natural maturation. Her use of colour is stronger and more chromatic, the objects more flattened and there is a greater simplicity in composition, but her familiar objects remain. Mary Fedden made it clear that her choices were not meant to be symbolic but were chosen for their own, decorative sake. She was infuriated by critics who looked for meaning and significance in her choices - “All I am trying to do is simply paint good pictures!”7

Three Red Poppies, 2003, Lithograph, 56cm x 63.5cm© the estate of Mary Fedden

In 1992, she was finally elected as a senior RA, and her 6 allocated paintings would sell within minutes. Dealer, Jonathan Horwich, remembers that an exhibition of her work in Cork St, people were queuing to buy her work and were being limited to only three paintings each. Towards the end of her life, her pictures were selling for over £100,000, and her accountant told her that in 1989 she earned more in that year alone than she had for the previous thirty.

She lost none of her spirit of adventure either in her 90’s. Invited by a friend to take a trip on their powerful motor cruiser across the Solent, she was asked if they ought to slow down. “Certainly not,”she replied, “Go faster if you like”. She then took a trip to the south of France on a private jet, while there sitting sketching on the terrace just as she had done in Sicily seventy years before.

Every possible moment of those last years were spent painting, going to work each morning to the studio and everything that she created sold. She remained in very good health until a couple of years before her death, when she fell outside her home while posting letters. A group of young lads, who she described as “hoodies,” came to her rescue, calling for an ambulance and remaining with her until it came. When asked if she was going to retire, she declared, “Stopping is just not part of the plan”.

Mary Fedden in her studio in Chiswick, 2003 © Eamonn McCabe

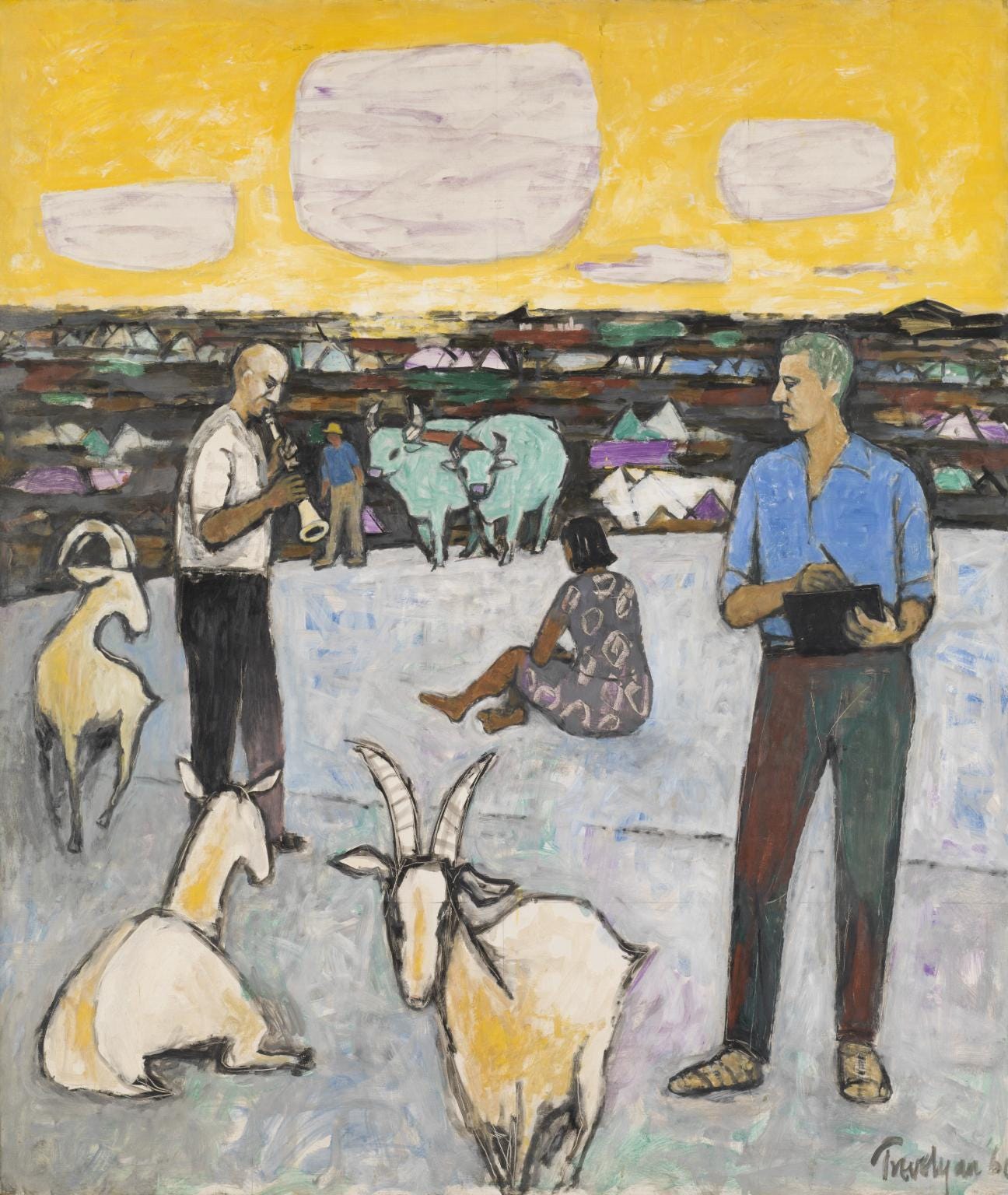

Self - portrait with Mary, oil on canvas, 1960, 146cm x 124cm ©Estate of Julian Trevelyan

Something to read

Still Life by Sarah Winman What else could I choose for this post, but this? If you haven’t read it, do. It is the most uplifting, joyful read and makes you want to take a flight to Florence.

Something to watch

A footnote to Jean Cooke , I discovered this film, A Delight in the Thing Seen, after I completed my last post and thought I should share it here, as it is so moving.

Here is an excerpt from a film about Mary Fedden’s art that I watched some years ago, and although brief, is a marvellous insight into how she worked.

And finally, a further quick survey of their work to see those images I simply couldn’t fit in!

I decided in this post to focus on the partnership of Mary Fedden and Julian Trevelyan, and the impact their relationship had on Mary’s work in particular. I tried to pick out works that would show the evolution of her painting and the influence that Julian exerted upon it. It quickly became clear that to go beyond her long and fruitful life, and to consider the paintings themselves, would be better served in a separate post - I love her work too much, especially the small gouache paintings, to not consider them carefully.

Thank you again for your company and, as always, I look forward to hearing your thoughts. Don’t forget to press the heart if you enjoyed this post (it really helps) and I look forward to seeing you again in a couple of weeks.

Do please consider subscribing as your support helps me continue to write here.

Further reading

Mary Fedden: Enigmas and Variations - Christopher Andreae

Mary Fedden - Mel Gooding

Mary Fedden and Julian Trevelyan: Life and Art by the River Thames - Jose Manser

Julian Trevelyan: Picture Language -Philip Trevelyan

Poppies, 2006, oil on canvas,79.5 x79.5cm © the estate of Mary Fedden

A collector of Mary Fedden’s work quoted in “Mary Fedden: Enigmas and Variations” - Christopher Andreae.

Mary Fedden, quoted in Mel Gooding, Mary Fedden, Scholar Press, Aldershot, 1995, p.87

Mary Fedden, quoted in Mel Gooding, Mary Fedden, Scholar Press, Aldershot, 1995, p91

Mary Fedden and Julian Trevelyan: Life and Art by the River Thames - Jose Manser, p82

Mary Fedden: Enigmas and Variations, p73

Mary Fedden and Julian Trevelyan: Life and Art by the River Thames - Jose Manser, p170

Dearest Deborah (🐝), another wonderful post! I studied history of art and design at university but find your posts are greatly adding to my knowledge and enjoyment! So many wonderful women artists I had previously missed out on (or maybe because I was at university over 30 years ago, many of these women had not been studied extensively?). Although, to be fair there was much of the 20th century I previously missed out on, eg. John Nash, Edward Bawden, Eric Ravilious, Cedric Morris etc. However, I digress! Thank you again for your fascinating posts. The Strawberry Hill pictures of both artists were interesting, Julian’s pink sky 😍, Mary’s magical figures 😍. Finally, as many of people have commented, thanks for the further reading suggestions. I haven’t read ‘Still Life’, but will add it to the burgeoning book list. 😂

Lovely! I’ve just finished reading Jane Gardam’s wonderful book, The Green Man, which was illustrated by Mary Fedden, so it’s great to learn more about her life. I noticed there are quite a few videos about Mary on You Tube, including this one showing 115 of her paintings: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XAHFQAdrHPs