August is a wicked month*

Revisiting Cedric Morris, fending off artist's block and finding lost treasure

My painting of Papaver Orientalis “Cedric Morris”. The poppy can be bought from Beth Chatto Nurseries

A very warm welcome to new subscribers and thank you for such a lovely response to my last post on Pembrokeshire. This month I am closer to home as I revisit the glorious work of the artist Cedric Morris and find a box of long lost treasure.

I am not fond of August. The harvested Norfolk fields are dusty and parched, and my garden, which is at its peak in late May and June, now looks tired and is desperate for a haircut. Until the golden, cooler days of September arrive, when I shall no doubt go wandering again in the fields and hedgerows with my sketchbook, there is often a fallow period when I never know quite what to do and inspiration sags. The most effective way to lift myself out of this “painter’s slump” is to have a jolly trip gallery-going to see work that will lift the spirits and will fire up my imagination again.

Years ago, when working in my garden in Norwich, spring to midsummer was spent painting the mass of flowers I could see from my studio window, but as July slipped by, I would turn to the produce of the garden: big paintings of glaucous red cabbages, artichokes and arrays of Turk’s Turban and Sweet Dumpling squashes. This year, when the inevitable fallow period happened again, it serendipitously coincided with the opening of a new exhibition, “The Art of Cedric Morris and Lett-Haines”, the artist plantsman whose work is a joyful expression of gardening and a dazzling, flamboyant life. It was just what I needed to bring back the colour to my jaded palette, but it also had unexpected unsettling consequences.

Cabbage and Walnuts, oil on board - a grainy image taken from my slide collection

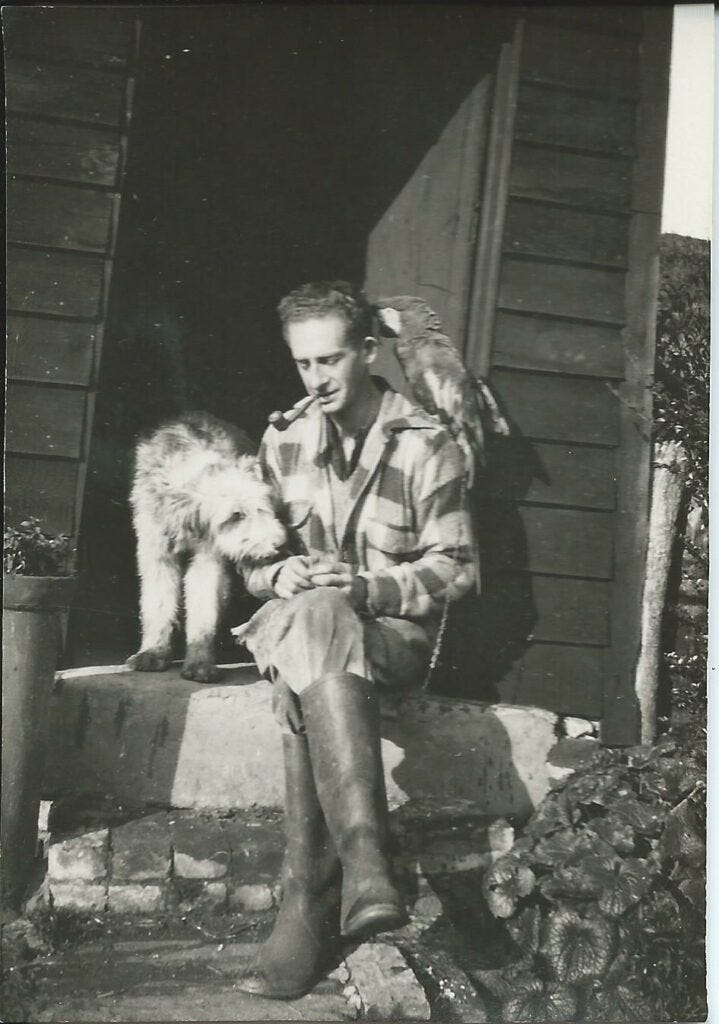

It was the first time I had seen his paintings in over 20 years. The last occasion had been at an exhibition at Norwich Castle Museum at a time when Morris’ star was on the rise again, following a decline in interest since his death in 1992. This had focused not only on the work of partners Morris and Lett-Haines, but also on the artists they had taught: Glyn Morgan, Frances Hodgkins and Lucy Harwood, all of whom had been students at Benton End, the home of their unorthodox art school, nestled in the Stour Valley and was a testament to friendship and its success. Organised and run by Morris’ partner, Lett-Haines, it was a place where students sought to learn the principles of modern painting and gain a taste of bohemian life. Although there was little formal tuition, each student was gently encouraged to find their own direction. Alongside the students was an exotic parrot called Rubeo, a rabbit called Maria Marten 1 who perched on Cedric’s shoulder while he painted, numerous cats and dogs, all in an atmosphere where creative freedom thrived and conviviality and colour conquered dreary post war days.

Cedric sat outside his studio at Pound Farm, Suffolk c. 1930 with Rubeo on his shoulder

Gainsborough’s House © Cedric Morris Estate

I was lucky enough to know the artist Frank Pond, who had attended the school as a young man in 1944 and who spoke of his time there with great affection. He said arriving at Benton End was like suddenly walking into a technicolor film and his visits there changed his approach to art and life, giving him the courage to be bolder and more experimental. He had been so nervous travelling down on the train, wondering whether he would be good enough or accepted, but he encountered nothing but warmth and gentle encouragement. He recalled how at the chimes of midnight, Lett would bang a gong at the back door, calling, “ Karze peaz” and how all the cats would appear from around the garden and fields, as if this secret password was in a language known only to them, for their daily feast. Knowing of my love of Cedric Morris, he gave me a card from an exhibition he had attended of Morris’ work in the 1940’s, that is much treasured, and remains on my bedroom wall still.

…elderly ladies, hitherto timid watercolourists, could blossom into riotous colour and bold designs…Some who longed to enrol but hadn’t the money for fees were given free tuition if they proved to be serious, even if they were without perceptible talent. Kathleen Hale2

Oh, that such a school as this still existed! I confess that if I were given the chance to time travel, this is where I would choose to go.

The exhibition at Gainsborough House is a joy. To enter the rooms and see these vibrant paintings burst from the earthy, aubergine walls is both life-affirming and deeply moving. Morris worked primarily in oils, each one hewn in rich, textural impasto strokes. Frank Pond said his technique was like “knitting”, each built up with tiny strokes of colour and seemingly without any preliminary underpainting - he would work across the canvas, from corner to corner, stroke by stroke.

I had hoped that there might be some sketchbooks to show the development of his paintings, but on examining the archives, there seems to be little evidence of this, just a few spare pencil portraits, compositional landscape sketches and simple line drawings of particular plants. It seems that he painted from memory, sometimes taking a specimen from the garden to remind him, but mostly relying on his intimate knowledge and understanding of plants to build plant portraits. For me, that is what they are, not flower studies, but individual portraits revealing his love and understanding of what he grew.

A detail from “Flowers in a Portugese Garden”, 1968. You can see here Campanula persicifolia and sweet pea “Matucuna”, both favourites in my garden Copyright Philip Mould and Co, London

While his flower paintings are faithful renditions of his subjects, what makes his work so uplifting is his use of colour. His choice of hue is uniquely Morris: murky plums, muted violets, cool blues and soft primrose, heightened by opposing vermillion and tangy orange. This same palette can be seen too in his portraits, though his distinctive depictions often caused understandable offence in the sitter as they are certainly not flattering!

Mary Butts, 1924 copyright the Estate of Cedric Morris

His still lives reflect the produce grown and cooked at Benton End: a clutch of pastel eggs, a dish of sunray carrots and giant leeks - all could have been lifted from the pages of Elizabeth David, who was Lett’s cousin and who he claimed to have taught. Many past students have remarked upon the sumptuous meals Lett provided, seemingly much more in total than the pooled ration coupons, and he would complain ferociously that his offerings were under appreciated and were “pearls before swine”!

The vibrant work of Cedric Morris that sings from the earthy, aubergine walls

Wartime Garden, Oil on canvas 1944 copyright Cedric Morris Estate

When not painting, Morris was gardening. A pioneer of naturalistic gardening, a consummate plantsman and breeder of over 90 named irises, his garden can be seen in many of his paintings and, in his “Wartime garden,” we see rows of serried cabbages and sprouts with Scarlet Emperor runner beans that eventually became his famed iris beds. While I may not be able to buy one of his paintings, my garden is swathed each summer by the white rambling rose named after him, by his dusky oriental poppy and many of his irises that thrive in my poor soil.

A collection of my iris paintings are available as cards.

For many years the glories of this garden were almost lost, but the good news is that it is now being brought back to life after being bought by The Pinchbeck Charitable Trust and The Garden Museum. It is set to reopen as a centre for art and gardening next year. “Cedric’s ghosts”, the name given to his irises by Sarah Cook, who has tirelessly sought out these lost varieties, so that now we can enjoy them again in our gardens.

Another from my slides, poppies painted from my studio window

A chance comment from a visitor to my open studio about Cedric Morris, 30 years ago, led to a lifetime love of his work. I knew little of his paintings, that were rarely seen then and the discovering of a painter who shared so many of my preoccupations was a very happy one.

My paintings then reflected a love of my garden and what I grew, but writing this piece was bittersweet. My visit to the gallery prompted a trawling through my loft for a box of forgotten slides. I had been given a collection of Morris’ work on glass slides, discarded by the Tate Gallery when they were no doubt updating their archives, and rescued by the artist Peter Baldwin’s daughter who knew I would love them. There are dozens of them, some labelled, others mysteriously anonymous. Along with them were boxes of slides of my own work, of paintings now long forgotten and heaven knows where. Holding these up to the light, these lost friends flickered back to life. In the hope of retrieving them, I took them to be transcribed digitally in the hope that I would be able to bring back these “ghosts”, but when they were sent through by email, the colours had faded, the images were grainy and my hope of seeing them restored was lost. It is a strange feeling seeing past work again, they seem to me now to belong to another person, and perhaps though they bring such happy memories, it is time for a new preoccupation to develop.

Something to watch:

Watch the sumptuous unravelling of the Benton iris “Nigel” here.

Something to listen to:

Maggie Hambling was a young student at Benton End. Listen to her memories here.

Sarah Cook in conversation with Matt Collins Here you can listen to the story of how Morris’ irises were saved as she talks with the gardener who helped restore the garden.

Something to read

Outsiders: A Book of Garden Friends by Ronald Blythe A collection of essays on gardens, old friends and literary loves with exquisite illustrations by John Nash and John Morley. The essay on the last years of Cedric Morris’s life is especially poignant.

A Slender Reputation by Kathleen Hale One of my favourite books, this is the delightful autobiography of the creator of Orlando the Marmalade cat. A friend of Morris and Lett Haines, their portraits appear in “Orlando’s Silver Wedding” and “Orlando’s Home Life”.

Thank you for your company here and for supporting my work, it makes a huge difference and helps me to keep going as an artist. If you enjoyed this piece, please press the little red heart as it helps my post be seen by non-subscribers too. I look forward to seeing you again in a couple of weeks!

“The Art of Cedric Morris and Lett-Haines” is on at Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury, Suffolk until 3rd November.

* Earlier this month we lost the brilliant Edna O’Brien. “The Country Girls” was passed to me by my beloved English teacher and O’Brien was my first “grown-up” writer. She felt very exotic and racy to a fifteen year old eager to spread her bookish wings. Laura Thompson (

)has written a fine tribute to her here. Let me know your coming of age novels, I would love to hear!Maria Marten was name of the victim of the Red Barn Murder in Polstead, Suffolk in 1827 and it became the subject of a popular ballad.

From, “Benton End Remembered”, ed. Gwynneth Reynolds and Diana Grace, London, Unicorn Press, 2002.

Thank you, Nick! I shall be the first at the door when it reopens next year!

What a great piece. I came to Cedric Morris via Maggi Hambling's pictures of him as he was dying, and love his work - both painting and iris breeding. And those slide - what a treasured possession, thank you for sharing.