Constable, Curlews and the first Cuckoo

Take a Tube trip with me to South Kensington, walk the byways of Suffolk and then linger in the Peaks

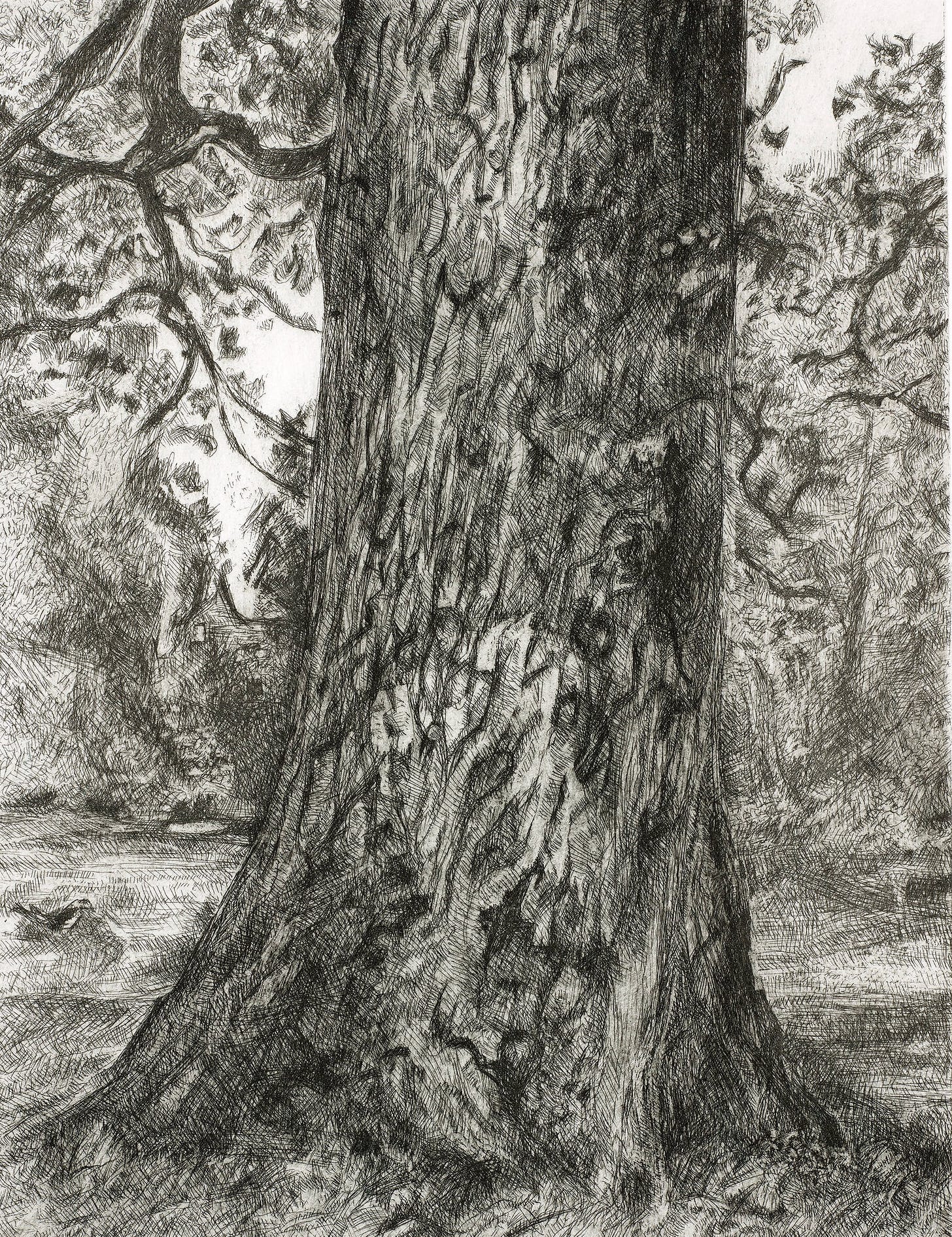

The Study of the Trunk of an Elm Tree, 1821, Oil on paper, 30.6cm x 24.8cm Museum no. 786-1888. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The world is wide, no two days are alike, or even two hours, neither were there ever two leaves of a tree alike since the creation of the world, and the genuine productions of art, like those of nature, are all distinct from each other - John Constable

When I arrived in London as a student from Wolverhampton, one of the many revelations of my new life, was having so much to see just a Tube ride away. My dear nan had given me an enticing entrée to its delights. She had adored London and each summer holiday she would arrange a day trip, the hours mapped out like a military operation, ensuring that not a minute was wasted, wanting me to experience London’s wonders just as she had done when she arrived to work in service 60 years before. We would feed the pigeons in Trafalgar Square, say hello to Big Ben, and walk through Hyde Park, where, on her day off, she had admired the horses of Rotten Row, and watched the nannies in uniform taking their charges for air - she said they always looked down on the other household staff, considering themselves “a cut above”.

Nanny had worked in South Kensington, rose from being a tweeny at 14 to a housekeeper at Prince’s Gate, had married at St Saviour’s, Pont St, and used to go to the Proms, dressed in her finest. Her love for London never faded, and when I chose to go to university there, she couldn’t have been more delighted, encouraging me to see all that I could.

My lovely nan with a painting I made for her

When I began painting, she couldn’t have been more proud. I never knew anyone who worked harder, but she loved her work and wanted me to do the same. In her late 80’s she took the journey by train to the Mall galleries and sat in front of my paintings telling everyone, “My grand daughter painted that…” She charmed the stiffest of visitors and I loved her dearly.

And so South Kensington became a special place to me too. A Sunday morning treat was a visit to the V & A. I would arrive just as it opened and wander the rooms that other visitors seemed to pass by. One morning I took a turning and found myself in a room of small, lowly lit paintings, and discovered that they were the work of John Constable (1776 - 1837) . They were nothing like the totemic, overwhelming “Hay Wain” in the National Gallery: these were intimate, exploratory studies, painted with rapid, sure strokes.

But there was one small study in the corner that held my attention above all the others. It was a painting of the trunk of an elm, with a fluttering of foliage and just enough sky to patch pair of sailor’s trousers, as nan would say. His attention was upon the cracks, crevices and patterns of the bark, blushed with lichen, and lit by afternoon light. I had never seen a composition like it.

Fifty years earlier, the artist Lucian Freud, also saw the painting as a 17 year old student:

I thought what a good idea. That’s the thing, I thought. Trees. They are everywhere. Do one of those. A close -up. Real bark. So I took my easel out and put it down in front of a tree and found it completely impossible.

He returned to the subject towards the end of his life, now ready to confront the challenge that had eluded him. This time he approached the subject as an etching, using black ink for the central trunk and a softer green black for the foliage and produced one of his finest prints.

After Constable's Elm, etching, by Lucian Freud, printed by Marc Balakjian, 2003, London, England. Museum no. E.1063-2003. © The Estate of Lucian Freud.

The painting was never intended by Constable to be an exhibited piece. It was one of 92 oil sketches left to the museum by his last surviving child, Isabel, each one painted on 2 or 3 layers of paper, glued together and pressed; it was a cheap and portable surface to work on. Some had images on both sides and one a child’s drawing on the back, which suggests that one of his children had sat sketching alongside daddy as he worked.

Barges on the Stour, with Dedham Church in the Distance, 1811, oil on paper. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

You can see where he has scored the paint to delineate the reeds in the foreground and scratched into the couds with the end of his brush

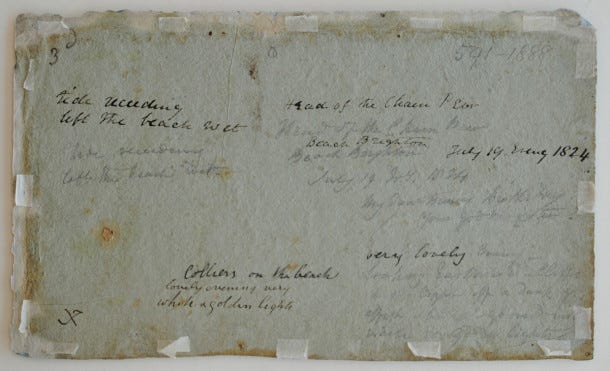

Constable’s images are so familiar to us now that it is difficult to appreciate how radical they were at the time. He turned his back on the polished history paintings of the period and chose to celebrate his beloved locale of East Bergholt and the Stour Valley instead. He made endless studies outdoors, in varied weather conditions and from different perspectives, working from “nature” and learning his craft. On the reverse of the studies he wrote notes, “Very lovely evening…looking eastward”, and marked the time they were made. His use of paint was radical too: mixed on the surface, alla prima, where you can see in his brushstrokes the urgency with with he tries to capture that moment. The paint is applied with vigour and energy and passion: there are splatters and ridges and sweeps, you can sense in these sketches his love for what he is painting. They are pure feeling.

Rainstorm over the Sea, ca. 1828-8, oil on paper, 23.5cm x 32.6cm © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

All these were sketches made in preparation for his “sixfooter”, showstopper paintings to impress the Academy grandees, who were slow to appreciate his innovative work, only electing him an RA at the age of 52 (Turner had been just 26.) But while I can admire these completed works, it is these that I love, because through them we can see how he reached this point. On Constable’s centenary, in 1937, the painter John Piper recognises the significance of these works:

His sketches mean more to us today than his big paintings in the end; they are so complete, vivid and timeless. … Constable … deeply affected the course of the [landscape] tradition and made the Impressionist movement, and ultimately the whole of the modern movement, possible and necessary.

Working outside, making a “close and continual observance of nature”, was radical too. Perched on a tripod stool, he used a pochade box where the paper was pinned to the lid and the oil paints housed in the tray beneath. Tubes were not invented until the mid-nineteenth century, so Constable used tiny glass phials of pigment and “bladders”, pouches of pig’s bladder tied up with string, to contain his paint. The next time I stagger along with a ruck sack stuffed with all manner of necessary kit, I need to remind myself of Constable and what little you actually need…

Constable’s pochade box, with detachable lid, on which the oil sketches were painted

Above all, these pictures make me itch to paint. I visited the V &A again a few weeks ago, and though the “Elm” is not currently on display, I poured over the others, looking for signs of the hand that made them. They are so intimate: there are stray hairs from the brush and dust blown into the wet oil. Knowing that they were made without any thought of being shown, that they were painted purely to explore how he could push the paint to convey “feeling” I found deeply moving.

Handwritten notes on the back on one of the oil sketches

These works also reveal the importance of hard work, and how frankly there is no substitute for it. There is little doubt that the sketch of the elm would have taken hours of concentrated work. He called these “laborious studies,” not because they were tedious to do, but because of the labour that was needed to learn his craft.

Until recently, my own work has always been focused on still life or subjects near at hand, but I have always wanted to paint landscape. While I love sketching outdoors, I have struggled to develop them into more ambitious pieces, because as soon as I returned to the studio, the spark that ignited the sketch seemed to disappear like a will-o'-the-wisp. Landscape is a very different discipline and I have begun to understand, through examining these studies, that is is learned by observing and sketching over and over again. So with days growing longer and warmer, here’s to more days spent learning and building a storehouse of memories in my sketchbooks and beyond.

Study of Dock Leaf, 1828, Oil sketch on paper, 15.2cm x 24.2cm, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This study were among those used for “The Hay Wain”.

Before I leave Constable, on the back of the “Elm” study is a label, author unknown, that I want to share. If you visit the V &A this summer, seek out these little sketches, it will be quiet and peaceful, and you won’t be disappointed:

At first sight, this study seems astonishingly 'photographic' in its acuity of detail, but closer examination reveals Constable's characteristic devotion to the physicality of oil pigments and paint-brushes. In particular, the treatment of the bark of the tree results in a tactile quality we usually only experience in the work of artists such as Velasquez and Chardin. They too were able to invest humble, ordinary subjects with a dignity and splendour. Constable would be surprised to find himself in such company, but would appreciate our recognition that - in his own words - his art was 'to be found under every hedge and in every lane'. He also wrote that 'the landscape painter must walk in the fields with a humble mind - no arrogant man was ever permitted to see nature in all her beauty'. We might also remember the anecdote Constable's friend and first biographer, Leslie, told: when William Blake saw a drawing of some trees by Constable, he announced 'Why, this is not drawing, but inspiration!'

Study of tree trunks, Oil on paper, 24.8cm x 29.2cm© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

As the blossom begins to leave us, I thought this study of light dappled woodland the perfect closing sketch. Note the patch of pale pink light behind the trunk and the olive yellow catching the edges of the roots. He is looking down on a mother holding a baby, who is formed by a swift, economic stroke and yet it is full of tenderness.

Every tree seems full of blossom of some kind & the surface of the ground seems quite lovely.

Something to listen to

Just before Easter, I visited the moorlands of the Peak District for a few days. My intention had been to spend the week sketching, but I experienced my worst flare -up of arthritis, and I found myself unable to draw at all. I found this so distressing and became fearful of the impact this was going to have long term. It has given me an even greater sense of urgency to “get on with it,” but the week yielded unexpected joys. In the field outside where I was staying were nesting curlews, and each morning I would sit and watch them sweeping their beaks along the ground, to suddenly rise, their haunting call drifting across the moorland. And then, on the last day, I heard the first cuckoo of Spring and so I have included Cosmo Sheldrake’s “Cuckoo Song” below, along with “my” curlews, so you can share them too.

Something to read

As the hawthorn blossom begins to open, it is the perfect time to read Melissa Harrison’s “At Hawthorn Time.” I read it when it came out in 2015, and it is a book I always think of at this time of year. I remember driving home from teaching through Suffolk villages feeling as though I was passing through the Spring landscape of the novel.

When I was in the Peaks, I wanted to read something set in the area, that would hold my attention when I was not feeling my best, and I found this: Stephen Booth’s first novel, “Black Dog”. I didn’t know of this writer (do let me know if you have), but this brilliantly plotted and suspenseful crime thriller kept me reading, as the curlews wailed outside, deep into the night.

I was so sad to hear of the death of Jane Gardam this week, whose work I dearly loved. I mentioned her wonderful novel “Bilgewater” a while ago. Henry of Common Reader writes a touching tribute to her here and, as he says, “May she be read”.

Thank you for your kind messages following last week’s none-post, they were so cheering. I am very grateful for your support here and, if you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing and do press the heart as it really helps spread the word!

Click to see my morning curlew

A curlew lifting its wings

And there were skylarks too

Further Reading

Orison for a Curlew - Horatio Clare

Constable: A Portrait - James Hamilton

Constable’s Skies - Mark Evans

Landskipping - Anna Pavord

Creative Landscapes of the British Isles - Bernard Price

Constable: A Painter and his Landscape -Norman Rosenthal

My linocut of “Cuckoo!” Available here

Oh, thank you for this, Deborah! I have a particular love of drawings and paintings of trees, but I didn't know about Constable's Elm. How wonderful.

Wonderful article, thank you! I hope your arthritis flare abates soon.