Honeysuckle and Sweet Peas, oil on board,H 45.5 x W 74.1 cm © Trustees of Winifred Nicholson. Image credit: Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums

This post exceeds the limit for images and will be cut short by your email, so do click on the post to see it all.

Flowers create colours out of the light of the sun…So I paint flowers, but they are not botanical or photographic flowers. My paintings talk in colour and any of the shapes are there to express colour, but not outline. Winifred Nicholson

With spring inching towards us, and our gardens begin to flush with colour again, it is the perfect time to turn to the work of Winifred Nicholson (1893 -1981). Her sunlight suffused paintings are the perfect remedy to the dark days of February. There is much I want to explore about this beloved painter, but today I will take a tour through a selection of her spring flowers. I can think of no painter who can capture a fleeting moment of light and joy better or bring spring a step closer.

Spring Festivity, 1966 Private Collection

It is beginning to be spring and there are wild snowdrops and white crocuses and blue glory of the snow, and borage, and hepaticas and primroses as common as grass. Our cherry blossom will be out soon, and the air is as clear as crystal. Winifred Nicholson , letter to E. J. Jenkinson, 18 March, 1922

Winifred Nicholson is probably the best known of the painters I have covered. She came from a liberal, aristocratic family and from a lineage of strong, pioneering women. Her grandmother was Rosalind, Countess of Carlisle, known as the “Radical Countess”, a promoter of women’s suffrage and of temperance reform, as well as an accomplished artist. She encouraged Winifred’s independence of thought and told her to seek a husband outside the ranks of the aristocracy ( a detail that amused me a great deal…) This privileged background meant that she was financially secure throughout her life. Unlike the other women artists I have covered, she didn’t have to teach, take on work that used her talents in other directions or have the necessity to earn money to survive. But, this did not mean that she didn’t have to fight to exhibit her work , nor did it mean that she was not a committed artist, she most certainly was. When life tested her, she continued to work tirelessly, when giving it up would have been all too easy.

As a child, Winifred received painting lessons from her adored grandfather, George Howard, 9th Earl of Carlisle, a self taught painter and great friend and supporter of the Pre-Raphaelites. She recorded the wild flowers in nature notebooks from his estate at Naworth Castle, following their daily walks together, dedicating one drawing to him, “Darling Granfy”. She inherited his paints when he died, and she took the decision to enrol at Byam Shaw Art School, where she studied until she was 26, receiving a rigorous training in academic drawing and where she made detailed, botanical plant studies.

This training also forced her to constrict her palette and she was criticised for seeing “too many colours” in her subjects, but later she wrote, “I was seeing colours in the irridescence that he [Byam Shaw] did not see - and I have been seeing them ever since”.

Cumberland Hills, Oil on wood, 1948 H 47 x W 45.6 cm© Trustees of Winifred Nicholson. Image credit: Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

Her early work centred on conservative, topographical studies, a natural consequence of her training, but following the War, on a visit to India, Ceylon and Burma with her father, the Under-Secretary of State for India, her eyes were opened to the brilliance of colour and she noticed “how eastern art uses lilac to create sunlight”.1 This revelatory visit changed the course of her painting.

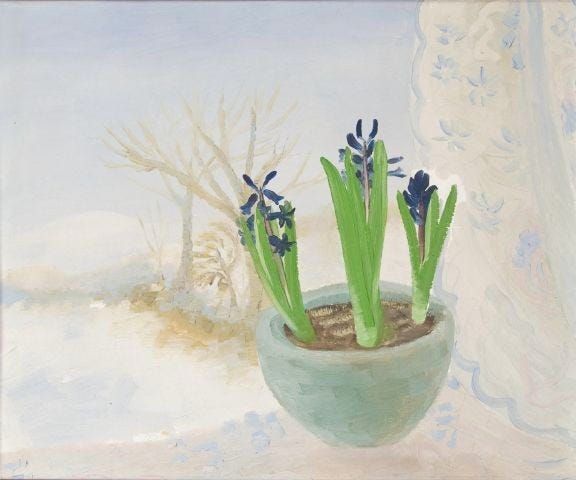

Blue Hyacinths in a Winter Landscape, 63cm x 74cm, oil on board, Private Collection

Shortly after returning from this trip, she met the painter Ben Nicholson. “Someone came into the hall and was talking…I could not see him…I knew in an instant that this was the person I would be marrying”. They did indeed marry soon after this, honeymooning in Italy and then spending the following three winters in Lugano, Switzerland, in a period of intense, creative energy for them both. Winifred remembers that her need to paint was so powerful that on one occasion she dipped her fingers in the oils, when her brushes had been packed away, to paint a subject that couldn’t be left. It was also during this period that her subject of flowers before a window became her main focus of attention.

Vermillion and Mauve, c.1928, Oil on board, 66 x 54.5cm Private Collection

On returning to England, in 1923, the pair exhibited their work jointly at Paterson’s Gallery in Bond Street, which Ben said consisted of 27 of “Winifred’s very sensitive flowers on one wall and my fierce blunderbuses on the other”. Winifred’s work sold well, but Ben’s did not. The success of the exhibition can be measured by how she bought Bankshead House, in Cumbria, upon its proceeds, a 17th century farmhouse that she would keep for the rest of her life.

To me they come when I am happy because then I am content to be quiet and still. Winifred Nicholson

Winifred notes that Ben was able to separate himself from domestic life while painting, whereas as she had to balance domestic and childcare responsibilties in a house that had no gas or electricity. Her daily routine was driven by a large black range, which provided both warmth and cooking facilities, and which appears in several of her paintings of their life there.

When Ben left Winifred for Barbara Hepworth in 1931, just after the birth of her third child, she was left shocked and devastated. It would have been easy for Winifred to leave painting behind, but she determined to continue, using any free time she could carve out from her increased responsibilities. At first he divided his time between the two homes, but when Hepworth’s triplets were born in 1934, it became more difficult for Winifred, and she saw little of him after this. It is testament to her generous spirit, however, that she maintained a friendship with him throughout their lives, corresponding extensively.

In 1932, her friend, the painter Frances Hodgkins, recalled that Winifred “had been having a certain amount of emotional difficulties just then, and she told me that all women had, and that’s why there were so few good women painters”.

I am very glad she persevered.

Below I have chosen four paintings, from many favourites, that particularly strike a chord at the moment. I would love to know your thoughts and, if you have a painting that brings you a sense of joy, do please let me know.

Four paintings

Cyclamen and Primula, 1923, oil on paper, H 50 x W 55 cm

© Trustees of Winifred Nicholson,Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge

I had always wanted this particular painting which I think must have been in a very early exhibition…; and then years later a Cambridge dealer had recognised it, so dirty as to be hardly visible, so he got it ‘for nothing’, cleaned it a little, and let me have it for what I could manage. Even then it needed a good scrubbing, and now is this delight of sunlit shadows and insubstantial substance. Jim Ede, founder of Kettle’s Yard.

In her early works, there is a clear sense of the inside against the outside. In “Cyclamen and Primula” above, painted just before they returned from honeymoon, we can see the bold line of the window’s edge, the strong shadows where the saucers sit, but the landscape is expressed only in a sweep of cool grey, against which the hot magenta flower buds sit. This is a colour that is often significantly placed, it was a signature choice that she felt was the most “light giving after white”. The pots too are still in their tissue wrapping, as though there has been an urgency to paint them. The brush is loaded with paint, twisted onto the canvas to describe their form, each stroke sure and bold.

Her paintings were completed quickly, in the fire of a creative spark. She would often form the concept of a painting, but then move on to the canvas, marking the layout with a pencil and would then work quickly, often completing a piece in one sitting, perhaps adding to it the next day, when she could consider it more coolly.

Easter Monday, Oil on panel, H 68.5 x W 68.5 cm© Trustees of Winifred Nicholson. Image credit: Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery

In this luminous second painting, “Easter Monday”, painted at her father’s home in Boothby, Cumberland, the vivid yellow of the daffodils and forsythia sing out against the cool violet blue of the garden beyond. The window is open to let in the spring air and the putty coloured curtains are barely suggested. There is no sense of the glass: the division between outside and inside has become blurred and the shadows and window frame diffused. Our eye is led instead to the lamp of yellow that glows from its centre, the suggestion of the other details give us just enough to interpret the image as a whole.

Winifred spent her whole life exploring the properties of colour, and was an intuitive colourist. Gazing at “Easter Sunday” I began to notice the technical skill of how this radiance is achieved. The is an overall coherence of colour, the use of cool colours against warm: the use of dull raw umber in the frame and curtains makes the yellow push forward. It is used again in the vase to the left and in the curtain rings, with just a hint of golden highlight, to link them to the flowers. It is all so effortless, but of course it is not.

Colour is one of the surest means of expressing joy…Winifred Nicholson

Winter Hyacinth, 1950’s, Oil on canvas, 61 x 62.2cm Private Collection

Each winter I perch a hyacinth bulb in a glass and watch the roots grow, defiant against the chill outside. Here she again uses neutral raw umber, with chilly pale blue and sets it against a warm deep crimson. The pale yellow roots push down to vermillion and just a hint of the first shoot emerges, with hope of the spring to come.

Early morning hyacinth last winter

Glimpse Upon Waking, Oil on canvas, 1976, H 60.6 x W 61.5 cm © Trustees of Winifred Nicholson. Image credit: Tate

Although the last painting I have chosen, barely reveals the hedgerow and fells peeking through the curtains, I felt I had to include this most hopeful of works, made when she was 83. She never stopped experimenting and though the subject of her work remained consistent, she continued to push the limits of her vision. Morning was what she felt was her most “sacred” time for painting and here you can almost hear the dawn chorus and feel the cool breeze wafting through, at the first sight of a fine day ahead. There is a streak of violet haze on the horizon, with pale primrose light above it. The ochre stripes lead us towards that centre, where nothing, but everything happens.

This sums up what affects me most about her work: she paints the ordinary, intimate moments of life, and elevates them into the extraordinary. We look beyond the frame and share the moment she captured and it lifts us too.

I have been ‘umming and ahhing’ about whether to add this, but I want my posts to reflect to the wider picture of a life beyond art too. The last few weeks have been a huge strain. I had fully intended to launch back into my own artwork after my big birthday, but life has intervened and aside from these posts, everything else has been put on a back foot.

My mum was taken seriously ill in hospital nearly a month ago, and as she lives on the side of the country, is almost 89 and while understandably wishes to remain as independent as possible, managing this situation has proved extremely difficult. Added to this, I am the only relative and so you can imagine what this involves. She is now at home with carers, but remains unwell and it is necessary just to take each day as it comes. Looking over Winifred Nicholson’s paintings for this post, my fingers itched to paint again and when I came across her words that life is never free from commitments and “emotional things”, it obviously struck a chord. My own painting and sketching trips have been put on hold, but researching these posts have helped enormously, giving me a focus and keeping me, mostly, sane! There will be a greater mix in the future, but at present, I will write as I can.

I don’t think I have ever found myself free from emotional things, that interrrupt your painting because if it isn’t your contemporary people, it’s your children, or your children’s children…and all the time there are human complications if you allow them to get in your way. Winifred Nicholson

Winifred Nicholson ©Jovan Nicholson

To be near Winifred was to be with a totally committed artist, for whom each day shed its light on a new theme for painting. ... Every painting is such an irrecapturable moment of life – she painted fast, each canvas the work of a morning or afternoon, some worked over perhaps the next day or the day after, but never laboured over in a studio for weeks. Kathleen Raine, poet

Something to Read

I have found reading difficult this month as my mind has been so scattered. I floundered around my bookshelves, and then remembered India Knight’s “Comfort Reads”, *which consists of her own favourites with additions from her subscribers. I chose Barbara Trapido’s debut novel, “Brother of the More Famous Jack”. It is the story of eighteen year old Katherine who is accepted by the left wing, Bohemian Professor Jake Goldman on his university Philosophy course, a meeting which transforms her life. It ripped along, with short chapters, is both funny and deeply touching, and it was just the ticket.

And then this made me remember Jane Gardam. She is one of my very favourite writers and knew she was the voice I needed to return to for solace. So I opened again, “Bilgewater,” that tells of seventeen year old Marigold, who lives with her headmaster father, at an all boys school in North Yorkshire. She is called the horrid Bilgewater as it is a cruel corruption of “Bill’s daughter” by the boys. A coming of age story, that hopefully, will lead you to the rest of her marvellous novels, just as it did for me.

*I should say this is a paid post, but her writing is marvellous.

I have been so grateful to the community of Substack over the last few weeks. I have been dipping into Notes and Posts when I can, and the kind words and generosity of the community here has been so appreciated. It has brought fresh connections and perspectives to the artists and printmakers I have been exploring and has led me on new reading adventures.

Thank you once more for your company here. Substack is helping me keep afloat at the moment, and although my posts are currently free, my subscriptions are open. I shall be back, fingers firmly crossed, in a couple of weeks and I look forward to more of your comments and to seeing you again. ( If you liked this post, don’t forget to press the heart, as it helps spread the word and let’s me know you have visited, which is always cheering!)

Wild Flower Window-Sill 59.5 x 64.8 cm, Oil on canvas, Private Collection

This must have been painted in a couple of weeks time. Here are wild garlic flowers, vetch and pussy willow, along with a tiny pot of violets.

Further Reading

Winifred Nicholson - Christopher Andreae

Five Women Painters by Teresa Grimes, Judith Collins and Orianna Baddeley

Winifred Nicholson by Jon Blackwood, Kettle’s Yard Publications

Winifred Nicholson: Music of Colour - Kettle’s Yard Publications

Unquiet Landscape: Places and Ideas in 20th Century British Painting by Christopher Neve

Unknown Colour: Paintings, Letter, Writings by Winifred Nicholson by Andrew Nicholson

Winifred Nicolson: Liberation of Colour by Jovan Nicholson

Voyaging Out: British Women Artists from Suffrage to the Sixties by Carolyn Trant

From Blinks, an essay from 1979 from a touring exhibition of her work at the age of 80, published in“Unknown Colour”.

“Daffodils and Hyacinths” c.1950 -55, oil on canvas, H 58.5 x W 48.5 cm

© Trustees of Winifred Nicholson. Image credit: Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge

I like painting flowers - I have tried to paint many things in many different ways, but my paint brush always gives a tremor of pleasure when I let it paint a flower…to me they are the secret of the cosmos Winifred Nicholson, “The Flower'‘s Response”, 1969

I'm sorry your mum's illness is dominating your life at the moment, Deborah. It's so true what Winifred Nicholson said about life never being free of commitments and emotional things. I mean, of course, but so often more so for women artists than for men.

I knew next to nothing about Winifred, and it's an eye-opener to see her beautiful art and to realise that she was Ben Nicholson's wife before he met Barbara Hepworth. I already had thoughts about how Barbara's life must have been after she had triplets (having triplets myself – now aged 39 – I recall the absolute intensity of it when they're little!). I hadn't realised that Winifred had just had a third child with Ben when he went off with Barbara. One part of me thinks 'How bohemian'; the other, the pragmatist, thinks, 'What a rat!'

Thank you so much for this post. I love Winifred Nicholson and my family are originally from Cumberland, which I know well and feel a tremendous pull towards. So the landscapes suggested through her windows are also very meaningful to me, as well as the flowers in their jugs and jars in the foreground. That deep grey-purple sky behind the blue hyacinths in their glass, is exactly the colour of clouds laden with snow. The glimpse of a mountain fell seen through the windows is just perfect in colour and form. The yellow flag iris on the windowsill, together with the bluebells and pussy willow, would have been picked from the shallows of a lake that morning. Such a lovely collection of memories brought by her beautiful work. All this will help you through this difficult time, and all good wishes for you and your mother.