The Lyricism of Winter Trees

The drawings and paintings of Elisabeth Vellacott (1905-2002), a tale of persistence and revisiting Wuthering Heights

Note: To read the whole post, this will need to be opened in the app as there are more images than usual!

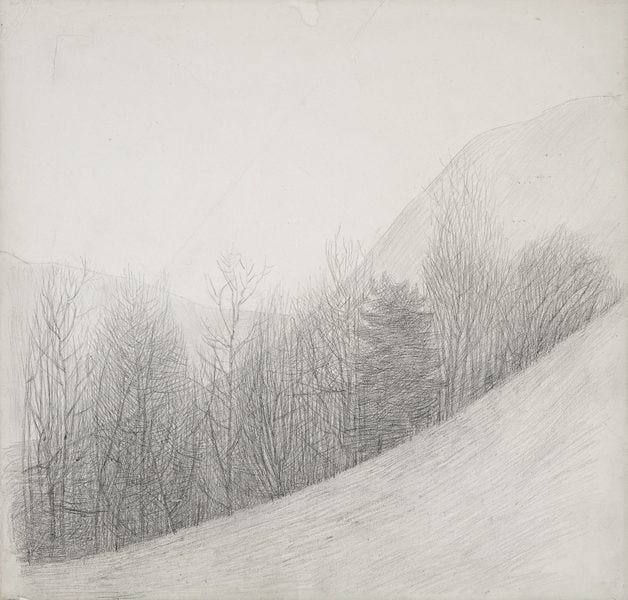

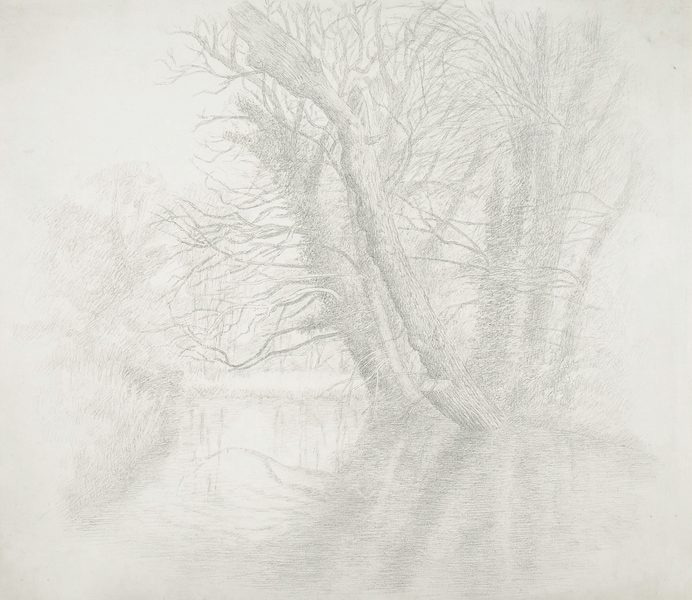

Bare Trees and Hills, graphite on paper © The Estate of Elisabeth Vellacott. Photo: Kettle's Yard 369 x 384cm c.1960

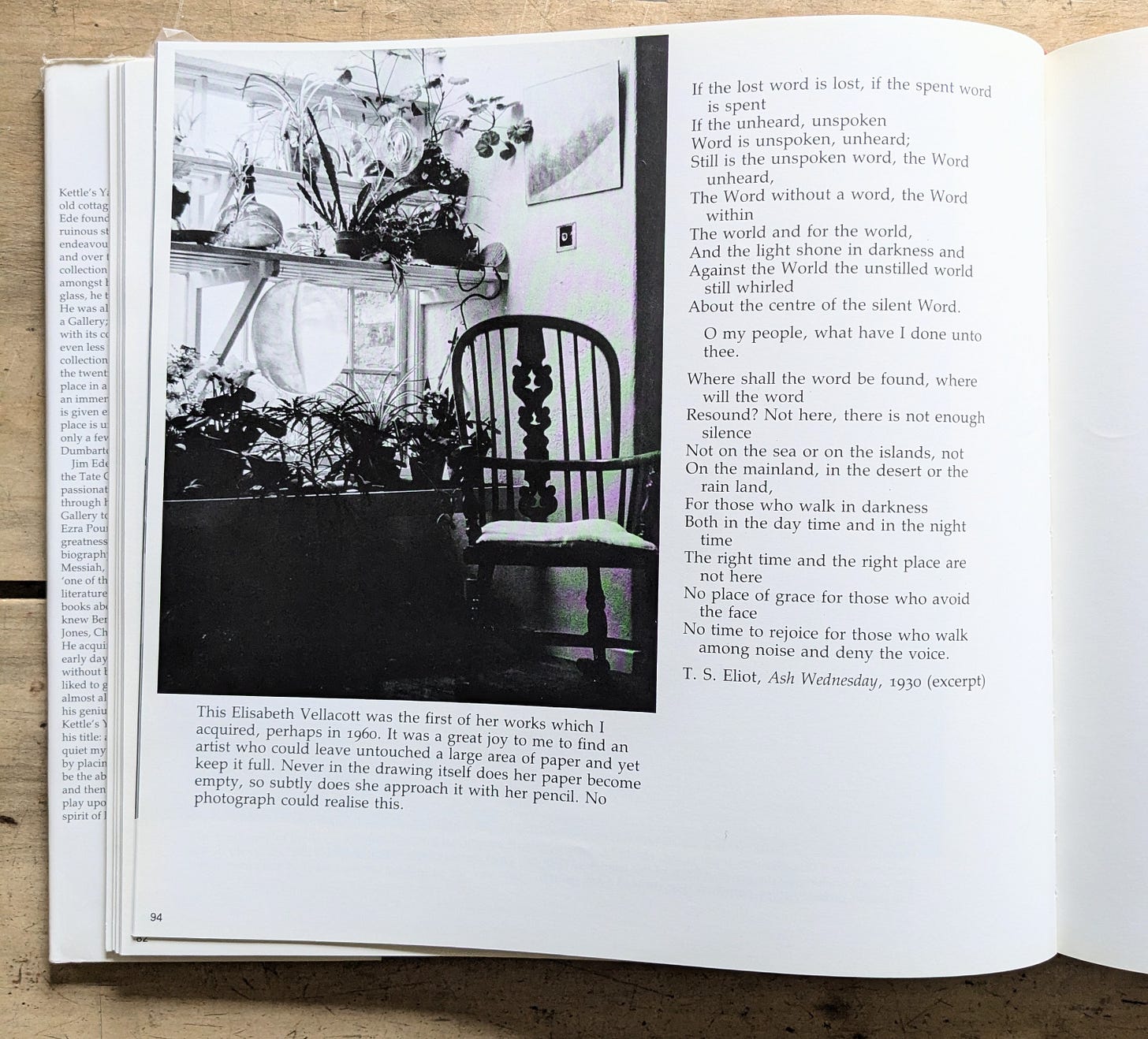

From “A Way of Life” by Jim Ede, the image shows the position of the drawing at Kettle’s Yard

January is not a good time of year for drawings - or perhaps what I can see from my windows is not speaking freshly to me - a thick fall of snow would give it a new look. I would really like to rearrange my trees as Morandi rearranged his bottles; but perhaps it is a good thing that all I can do is walk to a different position. From a letter by Elisabeth Vellacott

My first sighting of the work of Elisabeth Vellacott was on a visit to Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, the home and gallery of Jim Ede, art collector and curator. It was late January, a day of bitter chill and, as I walked around, I caught sight of a drawing, in a corner alcove, illuminated by a wash of sunlight. It was unobtrusively placed, alongside a collection of plants, and its subject so delicate, I could easily have missed it.

It showed a hillside, behind which lay a thicket of trees, described by a fretwork of sensitive pencil lines. The focus of the artist is on the interweaving of branches, observed with attention and heightened by a sense of space, the sky is blank so that our gaze is held by what the artist wanted us to see.

This is just one of her drawings bought by Jim Ede. He loved their spareness and close attention, but less so her paintings, which are very different: they show figures in a luminous landscape, appearing like actors on a stage. They are shapes of composed colour, have no shadows and in the later work, the facial features disappear altogether. I will show you both in this post and you can decide which you prefer. I would love to hear your thoughts.

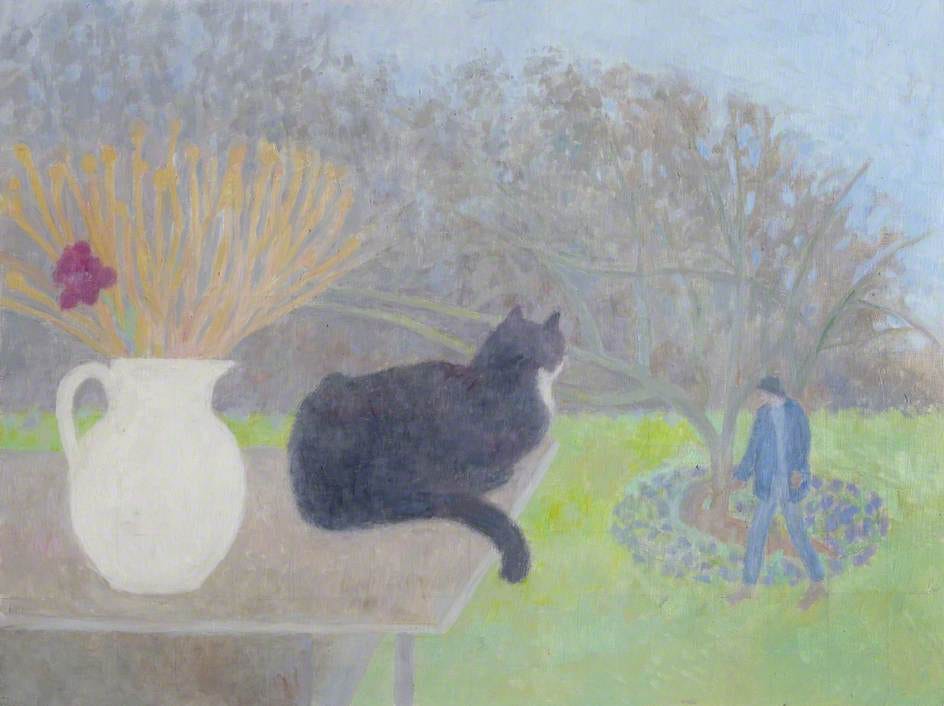

Garden Painting, bequeathed by Bryan Robertson, H 68.6 x W 87.6 cm, oil on board, 1976 © the artist's estate. Image credit: The Fitzwilliam Museum

As the cold has gripped us in the UK over the last week or so, and drawing outdoors has not been possible, I have been looking again at the work of Elisabeth Vellacott, and while I knew a little of her story, what I discovered of this mercurial artist has compensated for the lack of drawing time. Sometimes a subject falls into your lap just as you need to hear about it, and this certainly was the case here.

Elisabeth Vellacott was born in Grays, Essex in 1905 and decided at the age of 10 that she would become an artist. Her father, wanting her to “have her chance”, alongside her brother, hired an art teacher for her ( an aunt of the writer Graham Greene) and she entered Willesden School of Art in 1920 and then the Royal College of Art from 1925 - 1929. Single minded from the outset, she was frustrated by the academic teaching at the RCA, only responding to the life class by Thomas Monnington, who encouraged her to study early Italian frescoes and to visit the adjoining Victoria and Albert Museum. She would sneak through the connecting door from the Exhibition Road studios where she discovered “the marriage of nature and design in textiles and ceramics” and the collection of Chinese and Japanese art.

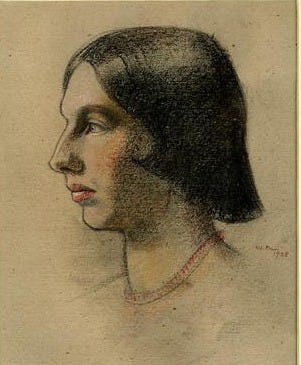

Drawing of Elisabeth Vellacott at the Royal College of Art by Sir William Rothenstein, 1928 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Her father died in 1926, and her mother while continuing to offer her “loving support”, found her daughter’s career choice less comprehensible. With only a widow’s pension, she was forced to take in lodgers. Older aunts and uncles felt Elisabeth was being selfish in persisting in her art education, and should leave college to help her mother, but Elisabeth stood firm, determined to gain her independence and make her own way.

In 1929, she returned to Cambridge, setting up a studio in Ram Yard, to earn a living in theatre and textile design. Then in 1931 took the post of an assistant scene painter at the Old Vic, but finding it impossible to live on the £1 a week paid by Lilian Baylis, who refused to pay her more, she instead took on costume commissions for the Cambridge University Musical Society, alongside the artist Gwen Raverat. Gwen, concerned at her young friend’s impoverished lifestyle, frequently drove her home after productions and bought her sensible presents, including a “thick, indestructible camel coloured dressing gown”. The two were to remain dear friends until Gwen’s death in 1957.

Evelyn Gibbs (1905-1991) Portrait of Elisabeth Vellacott signed and dated 'Evelyn Gibbs 1931' (lower right) pencil and red chalk 38.5 x 31.5cm Provenance: With The Redfern Gallery, London, where acquired by Quentin Stevenson in 2001

She had an entirely original type of face, as far from the accepted design as can be, yet so integrated as to be beautiful. Her expression was raffish, despairing and utterly charming, her voice and laugh delicious. Lucy M Boston from “Memory of a House.”

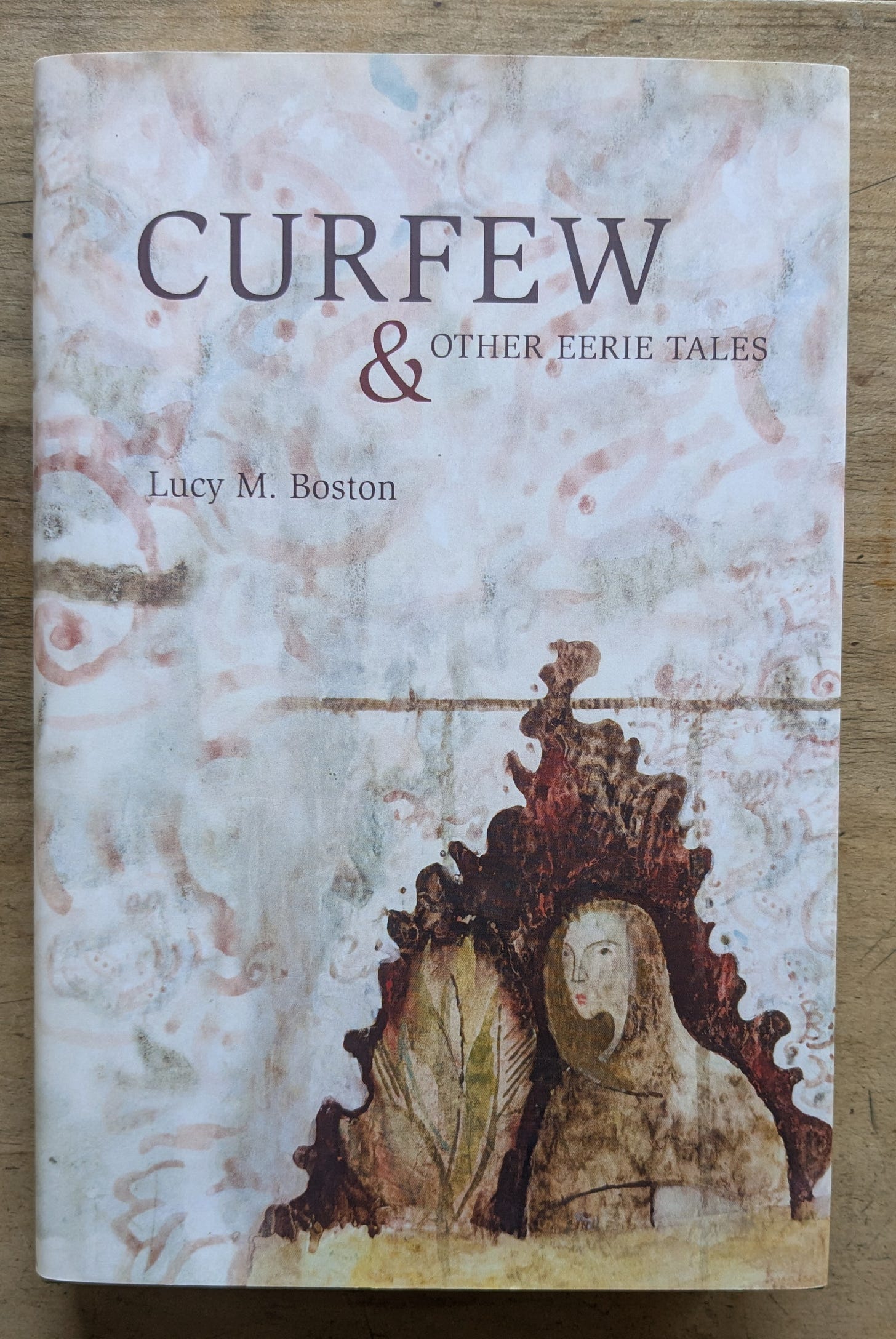

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Elisabeth met the other great friend of her life, Lucy M Boston, writer of the “Green Knowe” books, when she was billeted as a land girl, near Hemingford Grey. Lucy commissioned her to make panels and textiles to adorn the walls of the Norman Manor house, but while Elisabeth had “an infallible sense of design,” she had “no interest in practicality. At that time she sewed coloured sequins over her materials which though pretty were impossible to wash”.

Then in 1942, her studio was bombed, destroying all her early work. From the charred remains, she was able to rescue just ten tattered books and these, with characteristic resilience, she recovered in her own fabric. A friend commented that Elisabeth had had so few possessions and that it was particularly terrible to have lost those few she had. It was a huge set back, both in terms of the disruption to her work connections and the thread of her past work.

Lucy Boston offered her a home at the Manor, but the two friends were viewed with suspicion by the locals, suspecting them first of being witches, and then spies. Undaunted by such nonsense, the two arranged musical evenings for the RAF soldiers located at nearby barracks. They filled the double ceilinged room with all the single mattresses from around the house, including the back seat of Lucy’s old car, dressed in their finest clothes and played a programme of music on the wind up gramophone. The local padre would bus along up to 25 young men and these evenings would offer them respite and comfort. Lucy describes how, at the end of each evening, they were reluctant to return to their duties, and how “During each concert…we could hear the droning bombers flying overhead. From the absentees in the room we could guess who were among them”. When I visited the Manor a few years ago, Diana Boston played that same gramophone and we stood and listened, thinking of those airmen to whom such music had meant so much.

Airmen Seated, 1942- 5, oil on canvas

Elisabeth’s Vellacott’s painting of the RAF airmen attending a musical evening held at the Manor. I love how she conveys their wrapt attention and the glow from the candlelabra. Lucy Boston is shown at the edge in her evening finery.

Following the war, Elisabeth returned to Cambridge, securing a day’s teaching at King’s College Choir School which provided just enough income to continue her work as an artist. But she lived very frugally and friend, Jasper Rose, said that she would have only half an egg for lunch, something another friend disputed saying, “Nonsense, she’d have eaten the egg and had no supper”. Her determination to remain independent and, to be the artist that she had dreamed of at the age of 10, certainly came at some personal cost. In her late forties, it was assumed she would marry the sculptor Jan Ellison, but she steadfastly remained single, as she had “seen the talents of more than one RCA friend buried under a husband’s needs”.

Her work at this time differs greatly from that which emerged later in life. Its style and subject varies: there are ink wash drawings and oils, but there is a sense that she had not quite found her voice. Much of her work didn’t sell and would remain unsold for decades. And yet still she ploughed on. “I am horribly stubborn and haven’t lived these long years of privation and hard work for nothing…one of my theories is that a good picture will OUT like MURDER - this faith has kept me from despair”.

Bryan Robertson, a champion of so many lesser known women artists, including Mary Potter, became her torch bearer and showed some of her ink drawings in 1948 at the Heffer Gallery, and she had her first work published in a magazine. Such encouragement was enormously valuable at a time when it must have been very hard to hold faith in her work. He told her, “As an artist I believe you have made an extraordinary and absolutely personal statement, with absolute authority, and one day the truth will establish itself”.

The book cover of Lucy M Boston’s stories featuring an image made for her, Woman in Window, by Vellacott in gouche, in 1942-5.

Then in 1962 a visit to her beloved Victoria and Albert, to see an exhibition of Eastern art, took her back to her beginnings. She stood gazing at a panel and was suddenly struck - “this is what I ought to be doing”. She shifted from using canvas to working on smooth, white gessoed panels, working in thin layers allowing the light of the white ground to show through. Both drawings and paintings were made very slowly, her vision considered and distilled. Before painting, she would establish a “key” of colour, lifted by a “surprise accidental”, likening her work to a musical score.

The painting below, featuring her beloved cat Lulu, demonstrates this: the complementary tangerine of the twigs and the softs blues of the sky and clothing are lifted by the plum bloom. Everything is reduced to the simplest forms.

“Lulu”, Jug and Apple Tree, oil on board, 46 x 61 cm © the artist's estate. Image credit: Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge c.1995

Elisabeth Vellacott’s studio, designed by Peter Boston at Hemingford Grey

In 1959, she was forced to find a home again. Her house in Round Church St was to be demolished to make way for a multi storey carpark, but the answer came again from Lucy Boston. Elisabeth had received a small legacy from a relative and she bought part of an orchard, just five minutes away from her friend. Lucy’s son, Peter, an architect, designed her a house on a very small budget. He told her her money would stretch to “a roof but not to walls!” So an A-frame was constructed in wood and glass, with a kitchen, bathroom and spare room at one end and a studio living space at the other. Here she finally had a place of security, surrounded by trees that would provide endless inspiration for her drawings. In particular the pear tree outside her window, and the apple tree beyond, were to be her companions for the next 36 years.

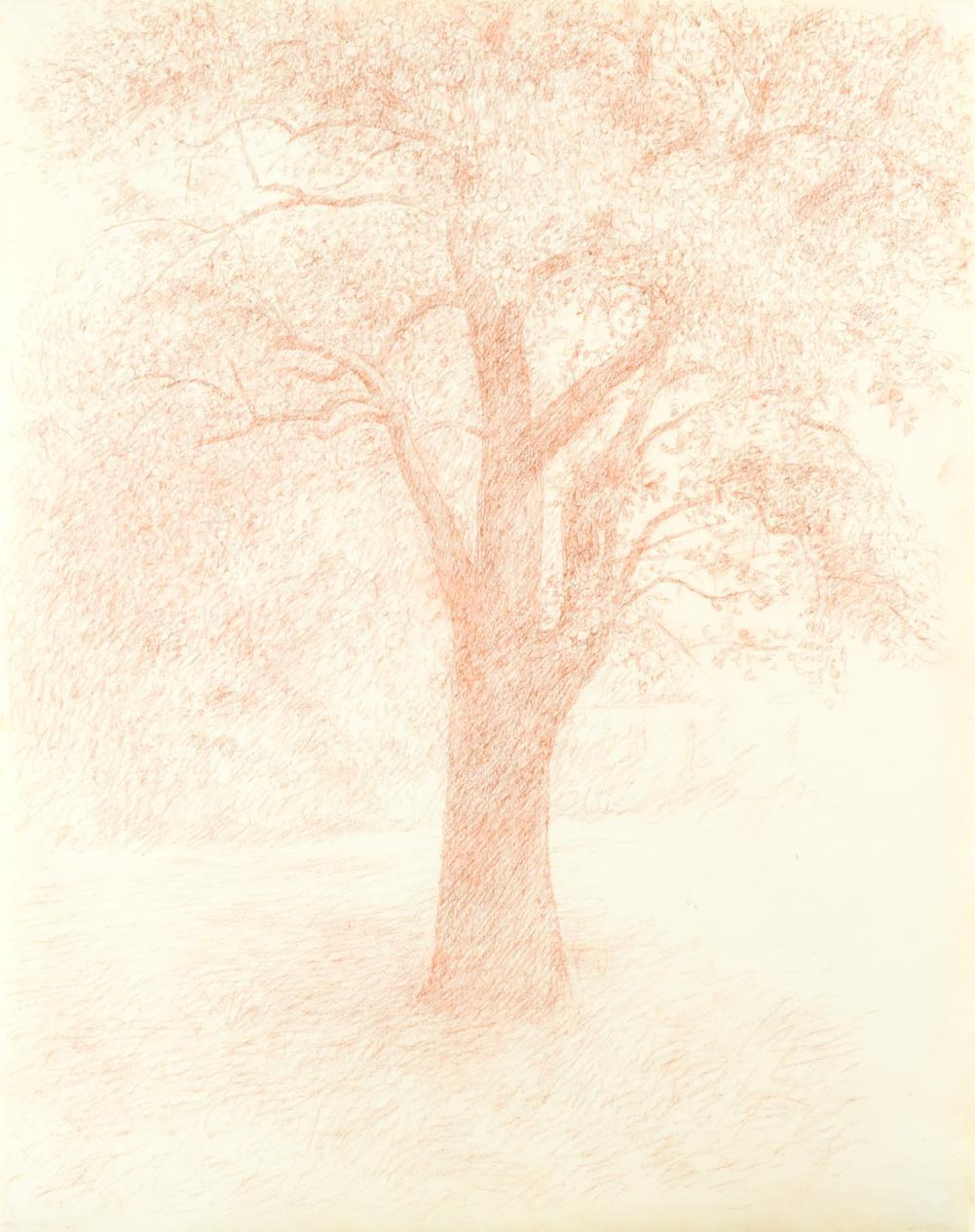

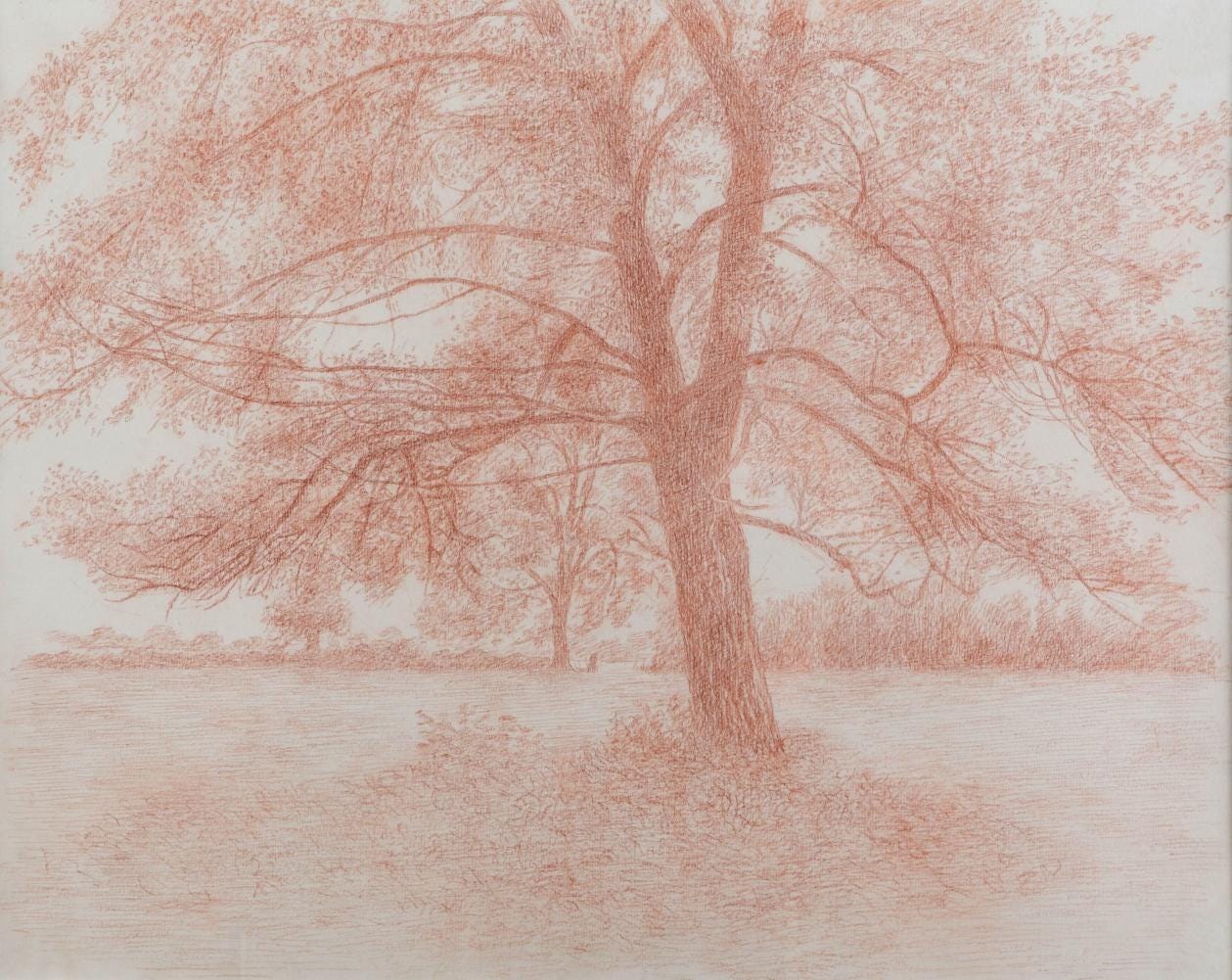

Pear Tree, coloured pencil drawing, 50cm x 40cm Private Collection

The Artist in Winter, 1984 signed, titled, and dated (to reverse) oil on wood panel 68.5 x 68.5cm. Exhibited: The Fine Art Society, London, Kettle's Yard and The Fine Art Society, July-October 1985, no. 20. Provenance: New Art Centre, London.

In her new home, her work slowly began to gather, although as her biography for a CPSS exhibition shows, she remained reticent: “Born in 1905. Studied at RCA. Now lived mostly in Cambridge. Exhibited very little. Chief interest: landscape”. She continued to draw, both at Cambridge Botanic Garden and studied Eastern art in the Fitzwilliam Museum.

Tree study, 1973 red chalk 46 x 58cm Provenance: With The Redfern Gallery, London

Then, at the age of 63, in 1968, the curator Michael Chase gave her an exhibition alongside the wood engraver Gertrude Hermes at the Minories Gallery in Colchester. She showed 12 paintings and twenty years of drawings, 40 in total, 17 of which were for sale. It was a success and her work was finally gained broader attention. It was seen by Caryl Hubbard and Madeleine Bessborough of the New Art Centre in Wiltshire, who had also been the saviour of Mary Potter. She was given her first solo show, and additional shows every 3 years until the end of her life.

She continued to work until her death in 2002, receiving a retrospective in 1981 at Kettle’s Yard and was still being hailed as a “discovery” into her eighties. Bryan Robertson, whose support she never forgot, wrote to her in 1997, “ What a superb and life-enhancing and inspiring contribution you have made to art - so many years of dedication, through good and bad times (adversity, poverty, illness and neglect). But you’ve beaten it all”. She was even the subject of a Southbank Show in 1984, a film I wish I could see, but have had no joy in locating.

How must she have felt about it all? Relief that she had finally received recognition following her dogged persistence to achieve that childhood dream, or was she perhaps more sanguine at her “sudden” discovery. In her later years, she was very much isolated and wished for greater connection with other artists to allow her to “judge (her work) in relation to other’s work”. Her isolation was increased by her encroaching deafness and the shaking of her hands, and her dear Lulu, who instead “to be drawn in her head”. While both her paintings and drawings are gentle and contemplative, there was a steely spirit beneath, which I greatly admire, and like her friend, Quentin Stevenson, I feel grateful for knowing her work:

Those of use who knew Elisabeth Vellacott are better for knowing her. For some of us it would not be too much to say that her friendship changed our lives, certainly altered our way of seeing, bringing to us, as it did, all the rewards of knowing and loving her and of finding her in her work. Quentin Stevenson

Thank you again for your company here. I was delighted that the work of Mary Potter in my last post spoke to so many of you. Please don’t forget to press the “heart” if you enjoyed this new post and do add your thoughts in the comments, or just say hello, I always love hearing from you. Please consider taking out a paid subscription, or buy me a coffee, to allow me to continue here. I look forward to seeing you again in a couple of weeks.

Trees and Water - Moat of the Manor, Hemingford Grey, Graphite on paper, 480 x 550mm, 1971 © The Estate of Elisabeth Vellacott. Photo: Kettle's Yard

Something to watch

I found this little film that features Vellacott’s painting “The Cellist with a Cat” ( featuring Lulu again!) with an accompanying Bach cello suite.

The Brontes Lived Her: Writer’s Houses This is only available for the next couple of weeks and what a gem it is. From 1973 a young Margaret Drabble visits Haworth Parsonage, the home of the Bronte sisters, and describes their life and work in an insightful and unflinching short film.

Wuthering Heights: The Read with Vinette Robinson I didn’t expect to enjoy this abridged reading, but was gripped for the whole hour. It is an astonishing performance by Robinson, who as Nelly Dean, tells her tale at the kitchen table, with such intimacy as to breathe new life in Cathy and Heathcliffe.

I do enjoy a Christmas jigsaw and what could be better than one that features the works and lives of the Brontes? Thank you

it was such fun!Further Reading

Memory in a House, Lucy M Boston, 2003

A Broad Canvas, Art in East Anglia since 1880, Ian Collins

Water Marks, Art in East Anglia, Ian Collins

A Way of Life, Jim Ede, 1984

Elisabeth Vellacott, The Redfern Gallery, 2003

Elisabeth Vellacott, Kettle’s Yard, The Fine Art Society, 1995

Gwen Raverat, Friends, Family and Affections, Frances Spalding, 2001

Vellacott's work is beautifully ethereal--so pale and luminous. I love the later paintings with the scarcely there figures. A lovely introduction to an artist I wasn't aware of.

Another wonderful new (to me) artist, thank you, Deborah. I find it hard to choose between her styles as they are so different. The ghostly line of trees in the first image grabbed my attention, but her oil paintings and strangely out of proportion figures are also really striking. Thanks for the insights.