All in black and white

The work of six pioneering women wood engravers and looking again at Jane Austen

A good print is as unlike a drawing as anything can be. Good draughtsmanship is, if it were possible, even more necessary in making a print than in making a drawing. Noel Rooke, Central School of Art, 1926

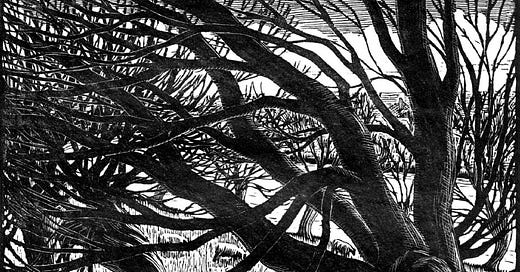

The image that started it all. The Fen, A Cambridge Landscape, 1935, Gwen Raverat (1885 -1957), 15cm x 17.5cm

As a young teenager, I came across a book in my local library, that lit my imagination. It was a collection of work by a group of female wood engravers. The cover is what I remembered most. It showed a landscape of willows in winter, at a river’s edge, their shadows stretched across the water and their outer edges lit by sunlight, with a group of sheep grazing on the bank beyond. Years later, after hours of searching and then Google to help me, I discovered the identify of the book and managed to buy a copy. 1

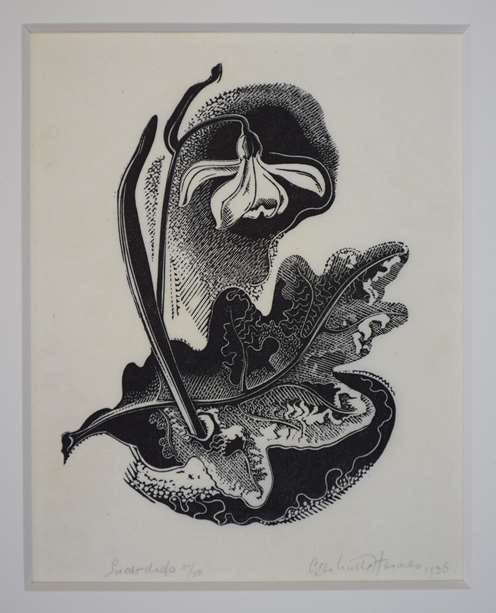

As an introduction to the women engravers whose work I had discovered all those years ago, I have chosen an example of a print from six artists: Gwen Raverat, Clare Leighton, Agnes Miller Parker, Gertrude Hermes, Monica Poole and Joan Hassall. These are a taster of what they created and, as you can see, each is very different in style. I will come back to them individually, along with others, in occasional future posts.

Clare Leighton (1898 - 1989), 1933, Apple Picking, 17cm x 12cm

Note the shadowy figure putting apples in the basket, delineated by a single white line

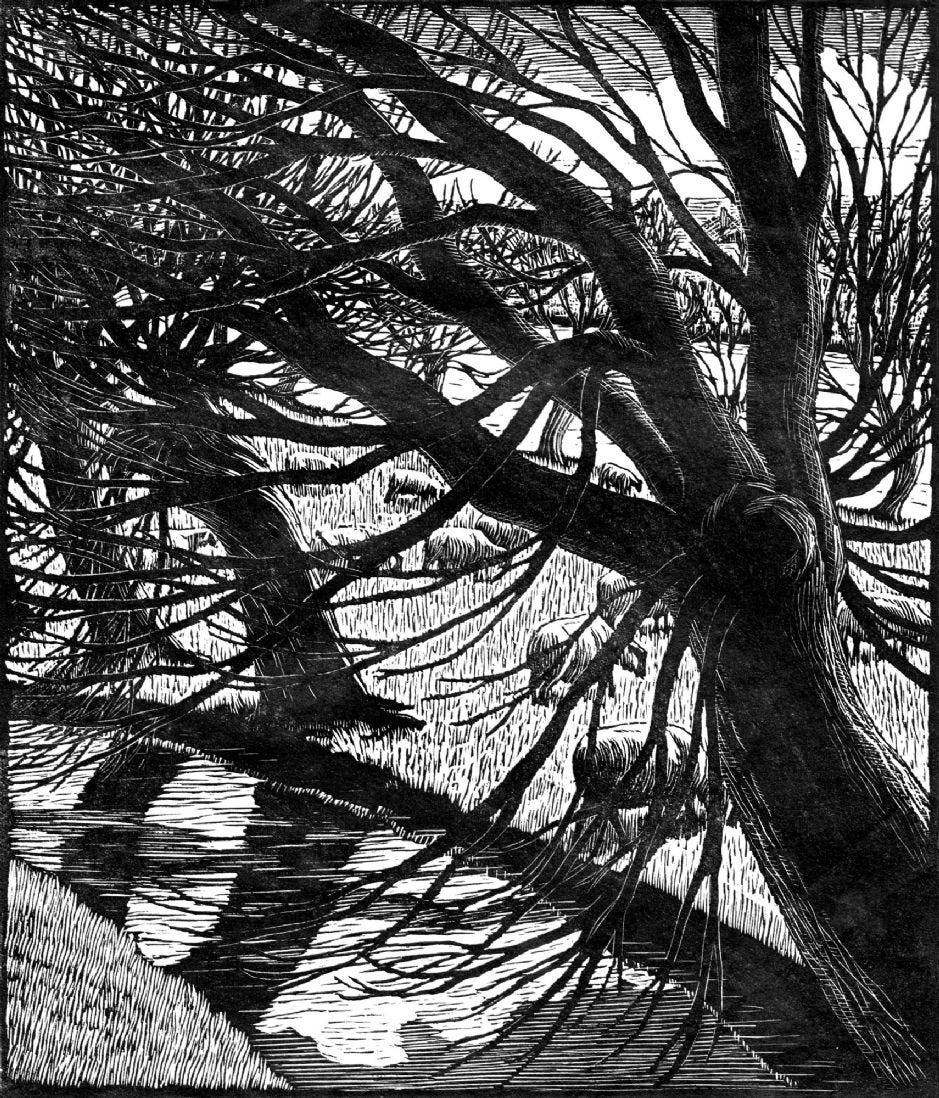

In reproduction, their work is often enlarged, to reveal their detail and the original size constantly surprised me. The interplay of black and white is handled differently too. Each is carved from the endgrain of a single block, usually boxwood, which is blackened with Indian ink so that each cut reveals the pale wood underneath. Each carved stroke reveals light and the image painstakingly emerges from the darkness.

Some of the artists I have chosen use broken lines to create half-tones, others cross hatching or fine, peppered marks. As in the case of Gertrude Hermes, a black amorphous, abstract shape enhances the pure white of the snowdrop petals making it shine from the darkness. Each print appears to have been drawn, or carved, from life and yet they begin as a simple sketch that is then developed by the artist’s own creative impulses as the subject takes a life of its own.

Snowdrop, 1936, Gertrude Hermes (1901- 1983)15.25cm x 11.5cm

I love here how she has described the fragility of an oak leaf laid on the woodland floor over winter

Wood engraving as a craft is one of the few artforms that has a purely English lineage. It was pioneered by Thomas Bewick (1753 - 1828), a Northumbrian engraver who used tools intended for metal on endgrain wood. The blocks were made so that they could be incorporated into a metal typeface. The illustrations could then be shown on the same page and could be printed off cleanly in greater numbers. Each intricate piece was no bigger than 5cm by 8cm.

A Barn Owl from “A History of British Birds” by Thomas Bewick (1753 - 1828)

The occupation remained in the male domain until the beginning of the 19th century. Apprentices to engravers often lived in their master’s household in dormitories and so females were naturally prohibited on this basis. Training girls was also considered to be a poor financial reward as it would be necessary for them to leave employment on the point of marriage.

“The Challenge”, 1934 , Agnes Miller Parker (1895 -1980), 14.20 x 16.40 cm ©the artist’s estate

This changed when educational opportunities for women expanded a century later: May Morris, daughter of William, founded the “Women’s Guild of Arts” in 1907 and “The Central School of Art” began teaching engraving in 1912. Reproductive engraving was now on the wane, and as it was no longer a secure profession, it seemed that women in the trade posed less of a threat. This in conjunction with the rise of small private presses, women finally had the opportunity to learn this rising discipline and it would provide the means for them to earn their own income without the need of a dedicated studio space.

And it was in this changed climate that this extraordinary group of women, whose work I show here, broke through to become some the greatest exponents of the craft.

Edge of the Wood, 1975, Monica Poole (1921 -2003) 19.5cm x 28.3cm

Alongside researching this post, I have been greatly enjoying “Miss Austen”, the BBC series based on the novel by Gill Hornby, which centres upon the novelist’s sister, Cassandra and her decision to destroy all but 160 of her sister’s 3000 letters. I don’t know the book, but I loved this series, particularly how it threw light upon their domestic life and how Jane Austen wrote her work. In her nephew’s memoir, he tells us how remarkable her endeavours were, “for she had no separate study to repair to, and most of the work must have been done in the general sitting room, subject to all kinds of casual interruptions”.2 While she was discreet about her writing, hiding it from servants and visitors, her family were highly supportive of her endeavours and in the evenings she would read extracts aloud to them. Her father was certainly, unusually for the time, encouraging of his daughter’s writing and her decision to remain unmarried was, it would seem, in part because she knew marriage and motherhood would have curtailed her work. She was well aware that marriage meant giving up her rights and property to her husband and the risks that childbirth held. Three of her brothers lost their wives to complications in pregnancy. While so much of Jane Austen’s life is myth and supposition, her novels demonstrate a clear understanding of the realities of an 18th century woman’s lot.

Joan Hassall (1906 - 1988), one of her illustrations for Jane Austen’s “Mansfield Park,” Folio Society, 1959

Here the artist uses lines, and cross hatching, in different directions to create variation in tone. The focus

is on the light Mary Crawford, whereas Edmund, against the window light, is in darkness.

I was also struck by how confined her working practice was. She didn’t have a study to herself, just a small corner of a shared room, placed next to an unused front door. Here, “she wrote upon small sheets of paper which could easily be put away, or covered with a piece of blotting paper”. The door to the room creaked, but she refused to have it oiled so that she could be warned of imminent visitors. My thoughts turned to our female wood engravers, working in similar domestic situations a century later, and how, like writing, it could be conducted in a small, private, carved out space within a family home, and how this could not be possible with an art such as painting. It was a medium that through its circumscribed requirements allowed women to become professional artists and flourish, in a sphere that had been previously male dominated.

In my perambulations about neglected female artists, I have always meant to turn to this group of women engravers, as artists whose work had led me to print in black and white, although in lino, rather than on woodblock. ( This was not a conscious decision, but rather that lino presented itself first!)

But I also wanted to share the work of those women painters whose work I admired and had collected on cards, and seen in books and galleries, about whom I only knew the barest facts. What I have discovered has amazed me. So much of their experiences resonated with my own life and working practice, almost a century on. But also in my reading I began to discover links between them, how their lives intersected, how strong friendships sustained their work as well as finding common ground in their personal lives and choices. I discovered the friendship between Elinor Bellingham- Smith and the writer Elizabeth Taylor, of Elisabeth Vellacott and Lucy Boston, of Clare Leighton and Vera Brittain. And the web grew, my list of women artists, some of whom I had never seen before, spread wider. Their subject choices and disciplines may have varied, but there were common denominators that drew them together.

It is a tragedy. Their work always deteriorates when they get married. Henry Tonks, Professor of the Slade School of Art, 1918 - 1930

Several chose not to marry, frequently finding it difficult to maintain financial independence; were often defiant against their parents’ wishes to become artists and those who did choose to marry, had to fight their corner to continue with their own work, or instead choose to support their partner at the cost of their own. In each case, the choice to become an artist came at some cost, and these are only the ones we know about. I was concerned that when I began, I would quickly run out of subjects, but each piece has led me down further rabbit holes and there is little fear of that happening.

I leave you with an artist who can stand for all those yet undiscovered women, the engraver Helen R. Lock (1884 -1967)3. She was known as a watercolourist who exhibited at the Royal Watercolour Society and the Royal Academy , but her extraordinarily accomplished engravings only came to light after her death, at the age of 83, when they were offered for sale to the print company T.N. Lawrence. Her print of “Hellebore”, perfect for this month, can be seen below, and, like so many others like her, her work should be seen and shared.

Jane Austen’s small, walnut writing table at Chawton, on which rested her writing slope

Jane Austen’s Ink Cornelissen produce ink from the recipe made by Martha Lloyd, Austen’s friend and maid, whose household recipe book was passed through her family. It was concocted using oak galls and beer, and is initially a blue-black, but fades to rich brown. Galls are easier to find on oak branches in winter, as they are not covered by leaves, and collecting a bag full is very satisfying. It is not complicated to make and is a wonderful medium with which to draw, or write novels! (You can see how I made oak gall ink here in a previous post if you fancy a go.)

Something to read

Letters to Alice: On First Reading Jane Austen - Fay Weldon Like Alice, the fictional niece in this epistolary novel, when I first read Jane Austen’s “Emma” for “A” level at school, I simply didn’t get it and remember railing against my teacher while he sighed at my blinkered view. Reading this during the summer holidays at university the following year changed that view and I realised what a radical, clear sighted and modern writer she was. Fay Weldon seems hardly spoken of now, but if you want to understand the social background to Austen’s novels, this illuminating and entertaining book is the perfect way to discover more.

Consequences - Penelope Lively I love the writing of Penelope Lively, but when I was reading Earth and Heaven, that I recommended last time, I remembered this and returned to it. Both novels feature wood engraving, in this instance with a brilliant talent, Matt, trained at the Grosvenor School; and from “Earth and Heaven”, Sarah quietly engraving her blocks amidst domestic tasks. Both show how significant an art form it was following the First World War. “Consequences”, follows three generations of women, each single minded and determined to forge their own, independent path, and I think it is one of Lively’s very best.

Something to watch

In this short film, Anne Desmet RA, demonstrates the process of wood engraving from sketchbook to pulling the test print. I think her judgement, “Not bad,” somewhat of an understatement!

In this film by illustrator Chris Wormell, who is entirely self-taught, he shows the origins of English wood engraving in the work of Thomas Bewick. ( Note his wonderfully chaotic studio!)

Thank you again for your company here and your much valued support. Do drop me a line in the comments and let me know what you think about the work of these women or indeed Jane Austen, I always love to hear from you. Do please press the “heart” if you liked this post as not only does it perk me up , but it helps these posts to be seen.

I hope to see you again in a couple of weeks!

A selection of my linocuts of birds

“Women Engravers” by Patricia Jaffe.

From “ A Room of One’s Own” by Virginia Woolf.

“Women Engravers” by Patricia Jaffe

Beautiful—both the wood engravings and the interplay with Austen’s story. I’m reminded of a recent exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario dedicated to European women artists who worked in a time when painting was impossible for many. There was a flowering of crafts, many textile-based, that could be easily put away when visitors arrived or domestic duties called.

Oh lovely piece thank you - I am fascinated by Claire Leighton; her book about making a garden is so interesting (Four Hedges) written in the thirties and very entertaining … and I so wanted to find out more about her after I read it; she was living with a left wing journalist at the time and later went to America but I couldn’t find any biographies of her … I wanted to know if she went on to make more gardens … all the things I come across about her (illustrating the work of Canadian lumberjacks at one point) make me want to know so much more !