An awfully big adventure

The colourful life of Kathleen Hale, the creator of Orlando the Marmalade Cat

Note: As I couldn’t bear to exclude any of the illustrations, this post exceeds the email length limit, so to see it all, you will need to click on the post to open it in Substack.

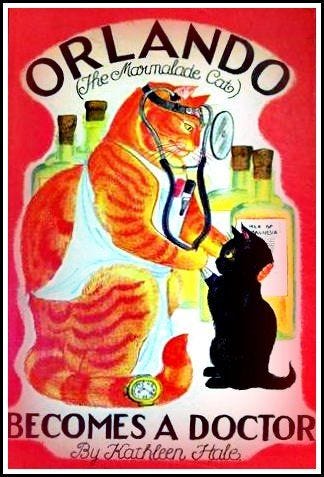

After what has felt like the longest January, I thought I would bring some colour and cheer in the form of the delectable Orlando the Marmalade cat and the story of his creator, Kathleen Hale, whose own life was just as colourful as that of her creation.

Although a contemporary of the artist of my last post Elisabeth Vellacott, Kathleen Hale (1898 - 2000) could not have lived a more contrasting life. While they shared a determination to be independent, and certainly a rebellious streak, their choices and career paths took them in a very different direction.

Born in Manchester to a comfortable and conventional Victorian family, Kathleen’s happy beginnings were turned upside down when her adored father died of syphilis when she was five years old. Her mother took the plucky decision to take on her husband’s role as an agent for Chappell’s pianos and sent her three children off to live with various aunts, until she could afford for them to be together again. Kathleen drew the short straw and went to Aunt Nellie, a tyrannical woman, who bullied her benign husband, and made the traumatised Kathleen wear a cardboard sign proclaiming “I WET MY DRAWERS.”

She returned to live with her mother four years later, but was always considered the naughty one, and her mother found Kathleen’s imaginative inclinations inexplicable. On arriving at Manchester High School, Kathleen “refused to be educated”, finding all lessons except art and English literature, boring “beyond endurance” and spent much of her time excluded from lessons, banished to sit in the corridor. She was nearly expelled for indecency when, idly drawing bare breasted mermaids around the edge of her religious studies book, her teacher Miss Crone became apoplectic, declaring her a child of “pernicious lewdness of mind”. Fortunately, the headmistress took a more tolerant view.

This headmistress, Miss Burstall, though “purposeful and purple faced”, brought in a new guard of young teachers. Miss Ritchie, who had studied in Paris with Frances Hodgkins, stopped the stultifying drawing of boxes to encourage the children instead to draw portraits of each other and, realising that she could capture a likeness, Kathleen’s imagination now had a purpose. She also gave them a photograph of a cat’s skeleton to draw, which had other far reaching consequences…

Recognising her talent, Miss Burstall, entered her drawings for a scholarship to Reading School of Art, which she was awarded. When she graduated at 17 she determined to go to London to find her way as an artist.

Kathleen Hale in the 1920’s

Understandably, her mother was appalled, insisting that she should at least take a course in shorthand and typing to fall back on, but Kathleen was adamant. “I am not going to learn to type. I am going to be an artist. You can send a policeman to fetch me, but I shall come back again and again”. And so, like Dick Whittington’s cat, off she went with “only a few shillings in her pocket”, her “pince-nez delicately chained to one ear and no qualifications whatsoever for earning a living”.

She found a room at a hostel near Covent Garden, first working for the Ministry of Food, calculating how much meat Britain was consuming, and then, when they realised how useless her figure work was, they moved her to painting maps of Britain in different colours. She failed to keep the colour within the lines, but she was kept on by ensuring “everyone was cheerful”. Then, one morning at breakfast, a “vision” descended the hostel stairs: the golden haired model of Jacob Epstein, Meum Stewart, who became her entrée in London art society.

The very glamorous Meum Stewart, 1919, the year Kathleen met her ©NPG

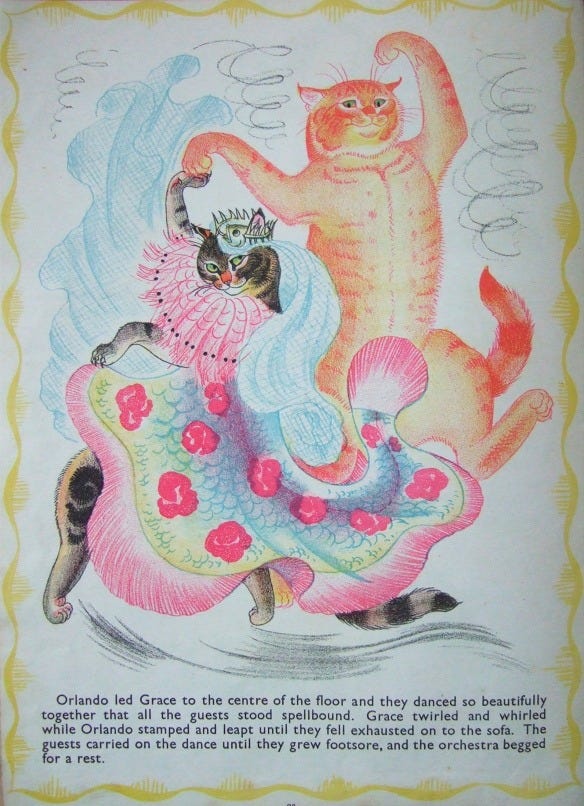

Kathleen joined the Studio Club, a shadowy dive when young artists and writers danced the night away. Dancing became a “new joy”, and she even won a box of chocolates at a public competition. This love she passed on to her characters, Orlando and Grace.

From “Orlando: His Silver Wedding”, 1946, showing Orlando and Grace in all their fishy finery. At the end of the party their garments were boiled up to make soup.

What is clear from these early memories of London life, is that Kathleen was loved by everyone. Her charm and humour won over even the most intimidating figures. The Studio Club had been run by a “large and fierce Cockney woman” and yet Kathleen alone managed to win her over, gaining extra helpings on her plate.

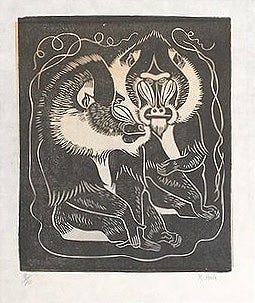

Outside work she continued to draw whenever possible, visiting Regent’s Park Zoo, when she could afford it, and drawing the animals. These sketches reappear in “Orlando Keeps a Dog,” where the animals audition for the role of a pet for the kittens; or in linoprint form, as in the one below. She later said that her sketchbook work became a repository for so much of what came later .

Mandrills, c.1920, linocut, 21cm x 17cm © Michael Parkin Fine Art

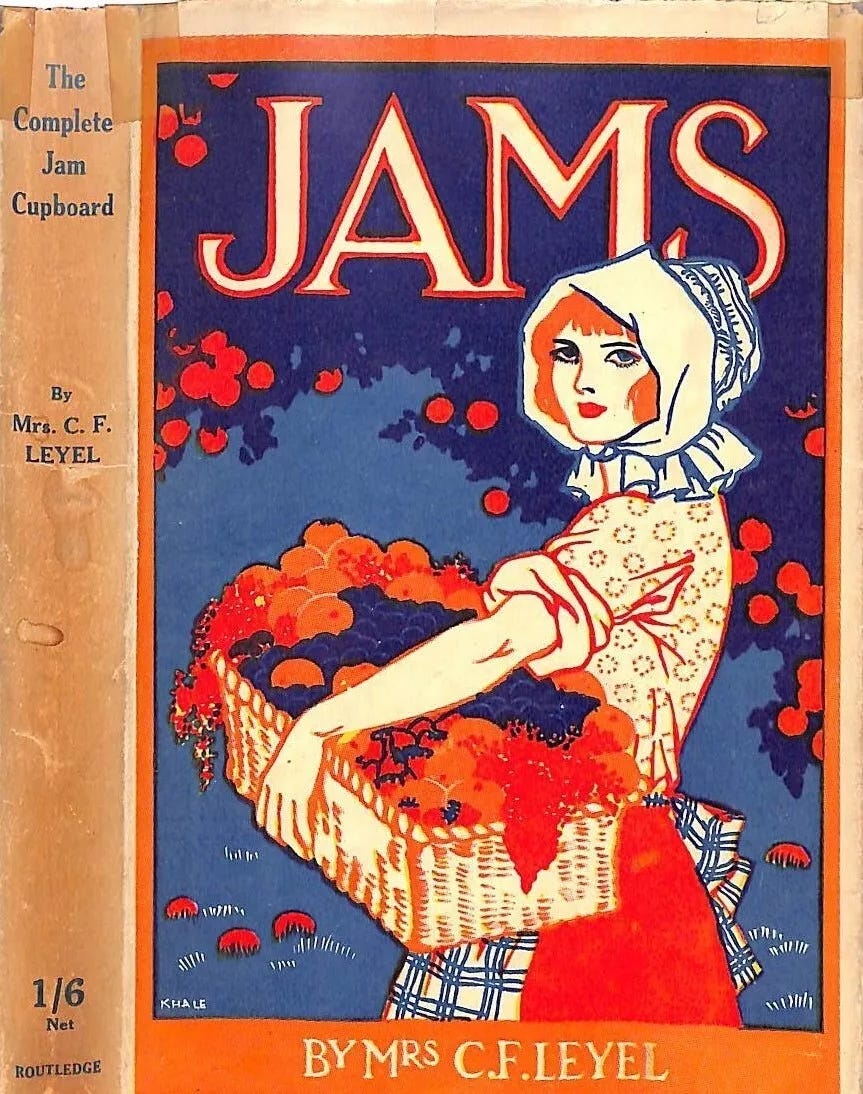

She was terribly poor, but managed to keep afloat by designing book jackets for WH Smith, and later other publishers, for which she earned 2 guineas a week, just enough to pay the rent. Taking a new room in Greek St, Soho, she longed to have a plant to brighten her room, but not being able to afford one, placed an onion in a jam jar and instead watched it grow.

After much searching, I was delighted to find this, one of Kathleen Hale’s

book cover designs from the 1920’s, in three colours.

Another of her designs, The Landswoman, the Land Army magazine by Kathleen Hale

When the WH Smith job came to an end, she became a debt collector for a window cleaner, sold a hank of her thick hair, became a film extra and then a poster design competition brought her to the attention of Augustus John, who had been the judge . He asked her about the work she was doing and she explained that she was scratching a living by whatever means she could find. He said this was “a monstrous misuse of [her] talents” and took her on as a live-in assistant, with meals included, for £2 a week. Kathleen’s charm had secured her a home at last.

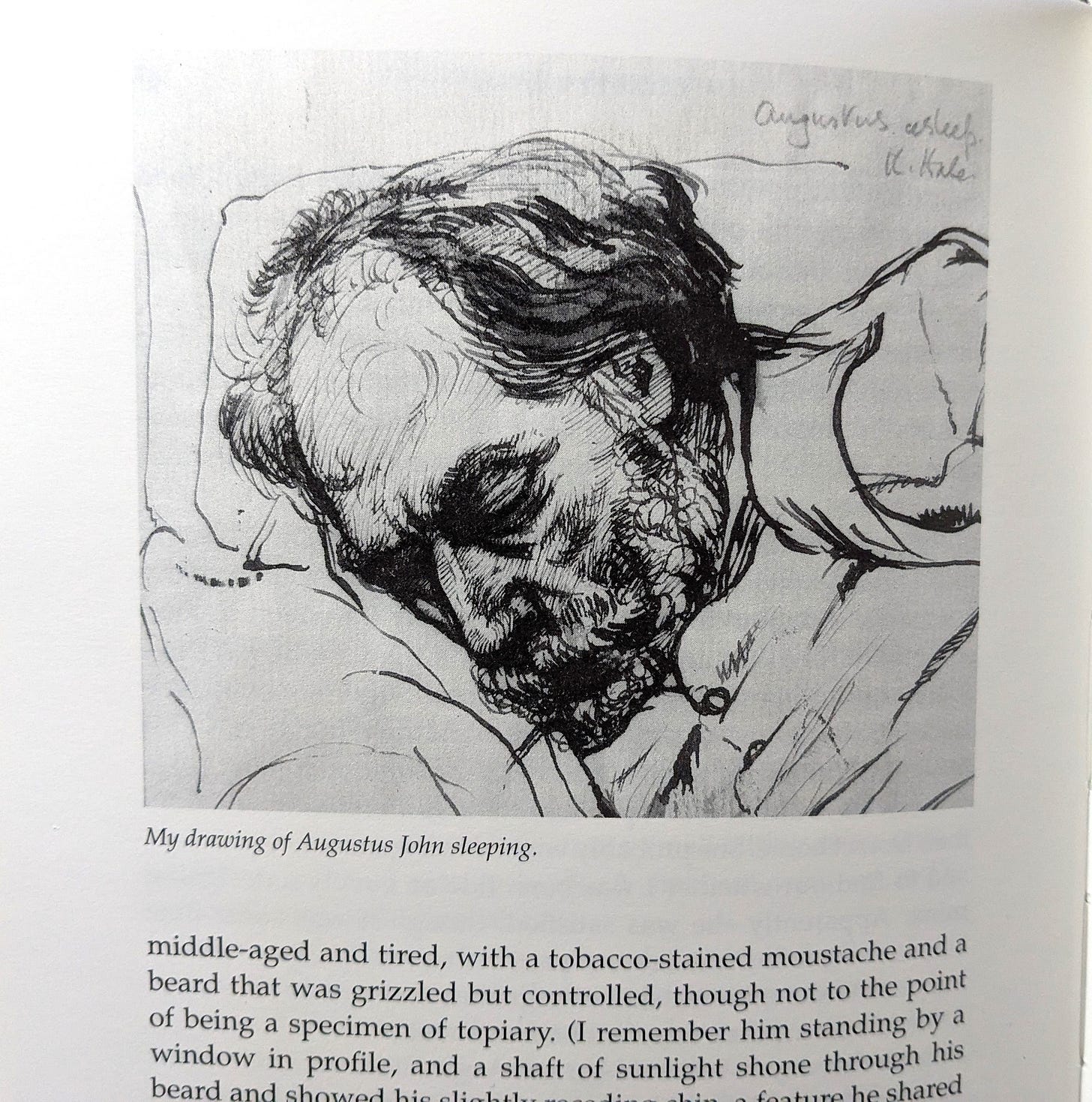

An exquisite pen and ink drawing, taken from “A Slender Reputation”, of her employer Augustus John.

Even without secretarial skills, she made herself indispensable. She squared up his canvases, sat as a model and looked after his impressive rich and famous clients, including T.E. Lawrence, Tallulah Bankhead and George Bernard Shaw. John even passed on a commision to her, but she couldn’t afford the oil paints, or the time to practise, and so she declined.

She worked for him for 16 months, but found his increasing demands ( he would call upon her constantly and she never seemed to have any time off) and she decided it was time to move on. A former lover, the sculptor Frank Potter, suggested they go to live in Etaples, to focus on portraits, and Kathleen always one for adventure, agreed. John told her she was a “rotten secretary, but a bloody good cook”. When he offered her a manicure set as a parting gift, she instead asked for three of his drawings, and he obliged by offering her many more.

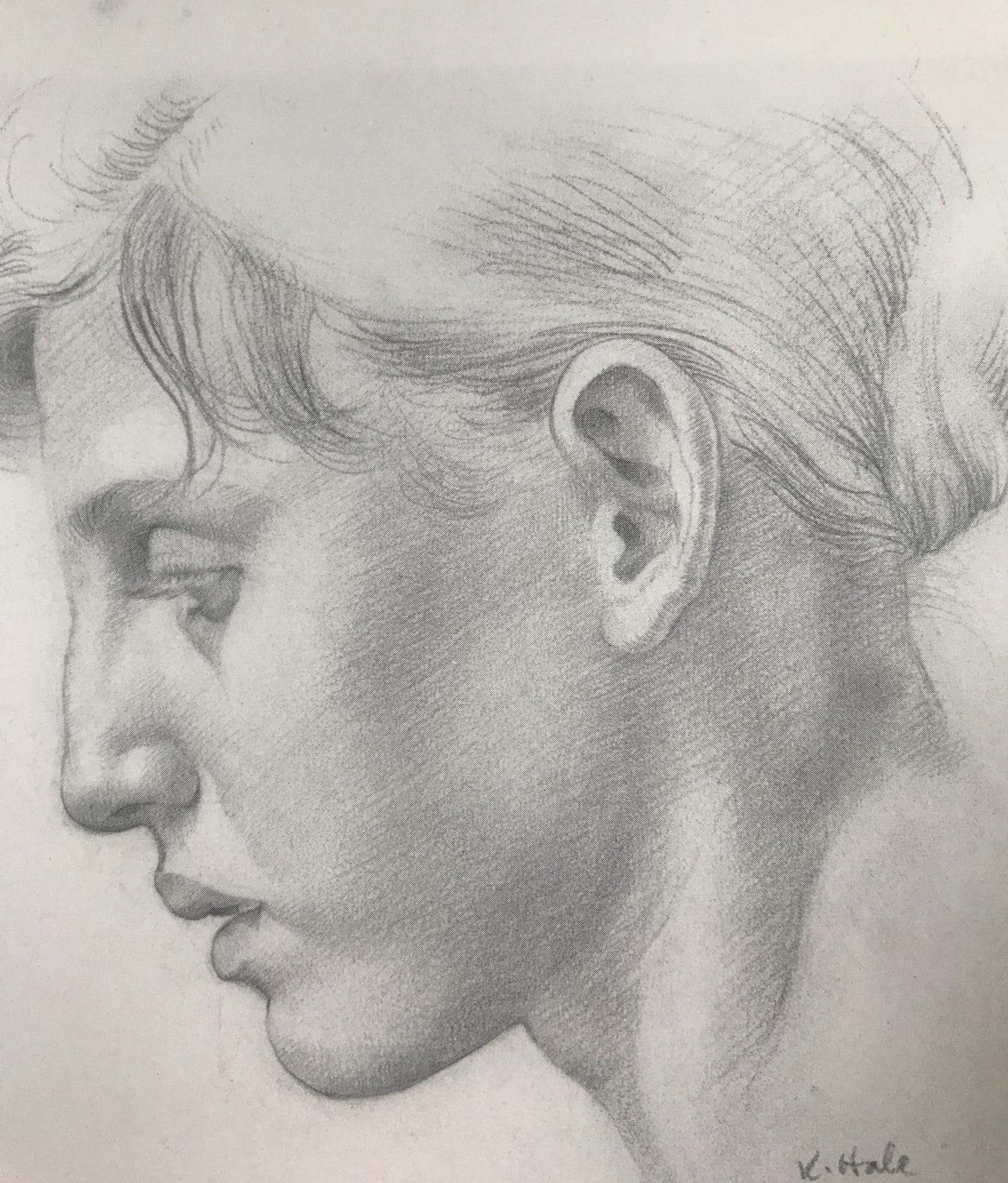

While in Etaples, she produced a selection of exquisite pencil studies, but when Potter’s friend suggested that the quality of her work was affecting Potter’s confidence in his own work, she decided she would return to London and leave the love affair behind.

A drawing from Etaples From Kathleen Hale Memorial Exhibition, ©2002 Michael Parkin Fine Art

Portrait of a French peasant woman with scarf, 1920 From Kathleen Hale Memorial Exhibition, ©2002 Michael Parkin Fine Art

She moved to Fitzrovia, glimpsing Sickert at his studio, and worked for three weeks on a decorating project for Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, whom she thought “snooty”, and who never “even offered me a cup of tea”. Grant, however, was much kinder and when she finished the job, declared to a mutual friend, “What a charming girl!” which may account for Bell’s frostiness!

Money was again becoming tight and she often couldn’t afford the gas meter or eat for a couple of days at a time. Work remained inconsistent and she remarks how she discovered the insulating properties of newspaper, after seeing a cat curled up on a pile, though she found its rustling noise kept her awake at night.

When at the end of 1923, she was admitted to hospital with a severe throat infection, due to malnourishment and poor health, she met the man that was to change the course of her life. Dr John McClean, the Medical Superintendent, while on his rounds sat next to her and accidentally pressed against her thigh. Having just had a painful injection, she shrieked out and so began “a great and loving friendship…I felt I had found my lost father”. At 66 years old, McClean was divorced with three grown up children and Kathleen loved him dearly. But McClean knew that their age disparity was too great and led her towards his doctor son, Douglas. The two could not have been more different: Douglas was serious, a scientist and liked the quiet comfort of home; she loved company, fun and adventure, but somehow the marriage worked, and following years of such insecurity and precarious living, one can understand her need for a sense of stability. She described their marriage as like “oil and vinegar”, their differences combining perfectly. But there were times in which she felt the “claustrophic” atmosphere of “domestic silence” oppressive and longed for more lively company after a day painting alone.

Fortunately, the bohemian life that she so missed came to her. The artists Lett Haines and Cedric Morris moved to a house in the next street and a friendship that had began in Paris, was picked up, and was to last all their lives. When they moved to Suffolk, and established the East Anglian School of Painting she went to join them, ostensibly for painting holidays, but no doubt also to escape domestic constraints.

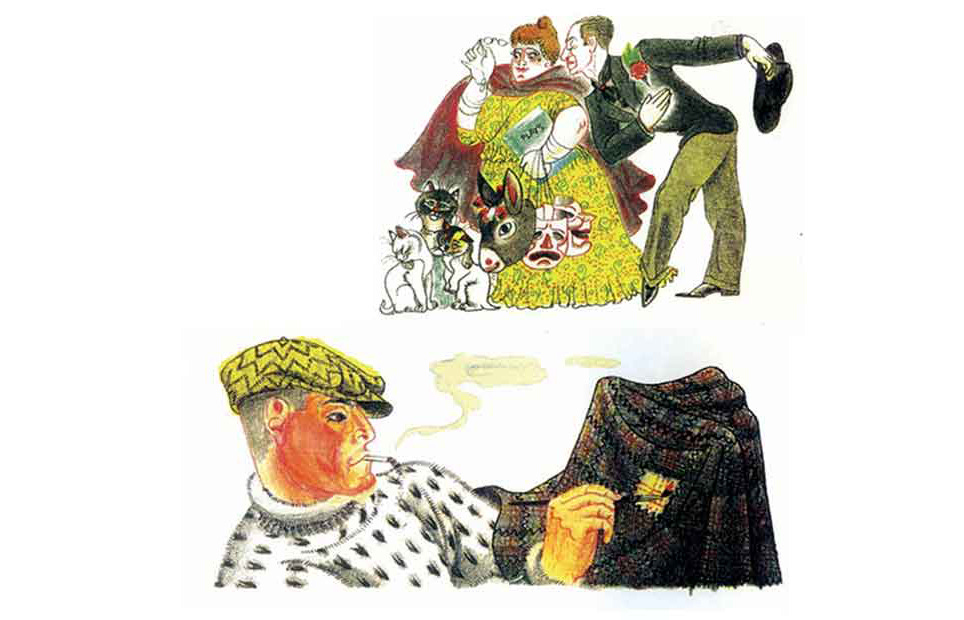

Lett-Haines appearing as the ‘Katnapper,’ glowering menacingly through the window, in the 1944 “Orlando (The Marmalade Cat): His Silver Wedding”

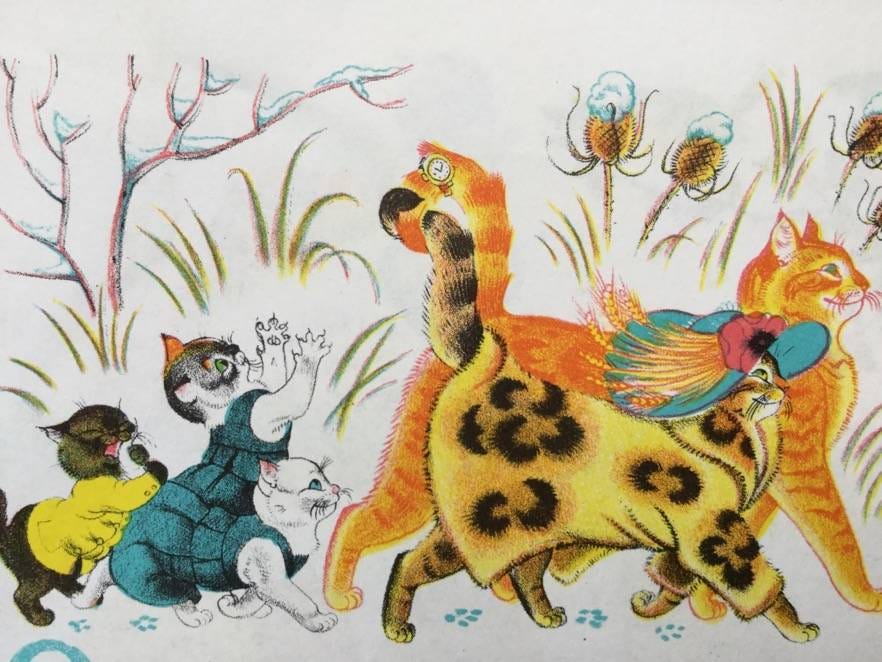

Cedric Morris appears as the dancing master above in Orlando’s Home Life (1942) and Lett Haines below, darning his jacket. Kathleen Hale tells us that Lett did just this, using white wool and painting it with watercolour.

They moved to the “ugliest” house in Hertfordshire, and there had two sons, Nicolas and Peregrine, jointly called the Perriniks. Douglas worked on the garden and Kathleen in her studio. They had a nanny called Nonk, a dog and a marmalade cat called Orlando…

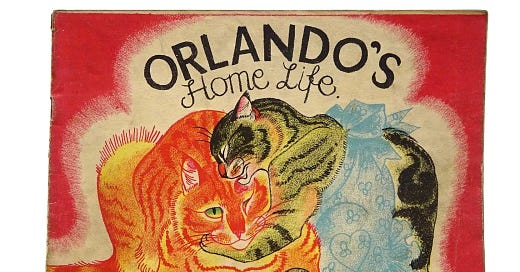

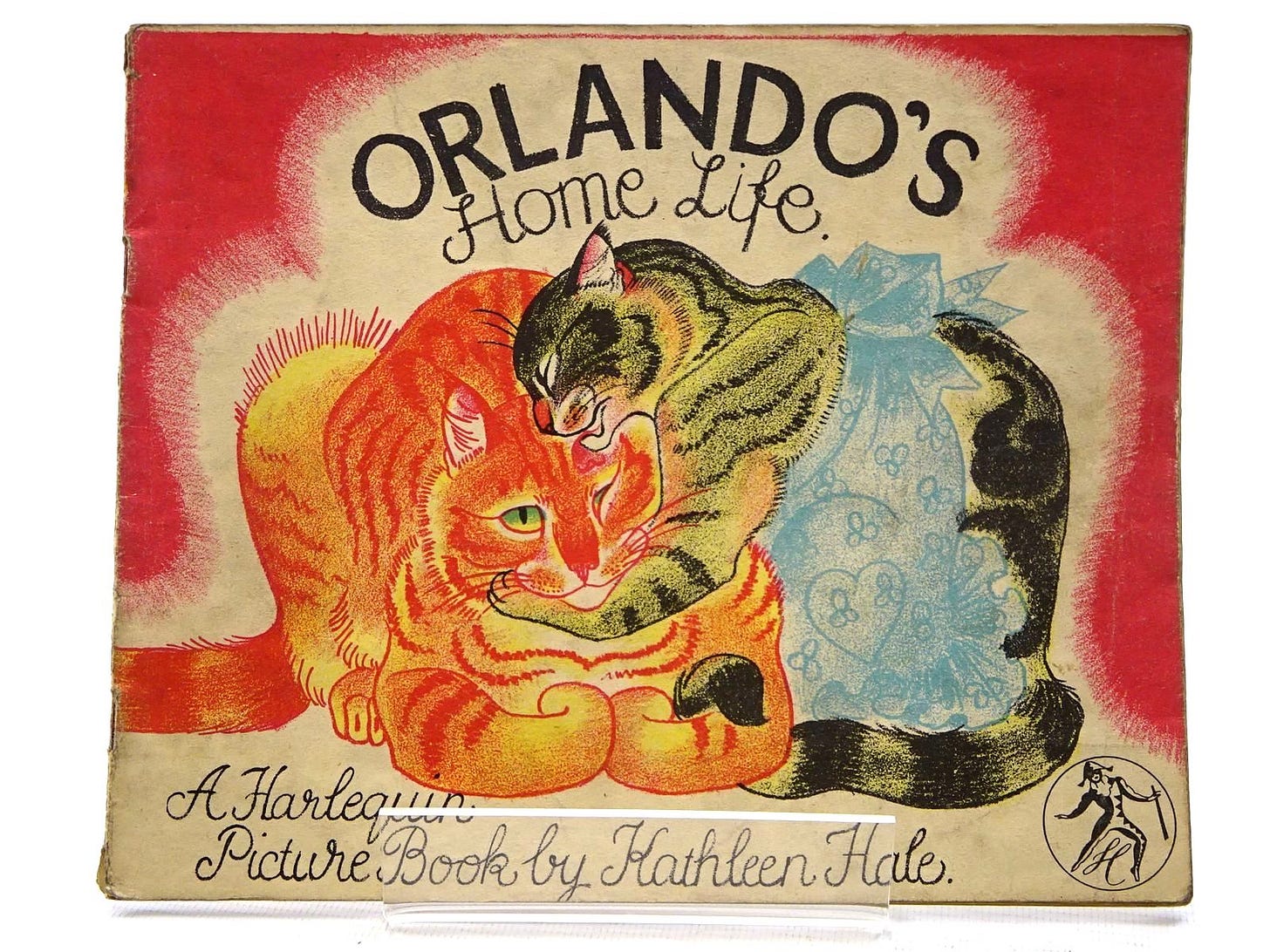

“Orlando’s Home Life,” published in paperback in 1942, Frederick Warne. I love his squashed face as Grace kisses him

The Orlando stories were created following her frustration at the lack of children’s books, having read the Babar books and Ardizzone’s “Little Tim” to her sons. She began making up her own stories, and Orlando the cat, based on her husband Douglas, walked into his first adventure, “A Camping Holiday,” published in 1938.

Initially unable to find a publisher, due the cost of production, Noel Carrington, Editor of Country Life, persuaded her to reduce the seven colours to four. By using a new lithographic process, using plastic plates on which the artist could draw, the delicacy and the detail of the drawings could be preserved. When the artist employed by the printers was unable to capture the fluidity and spontaneity of her work, she took over the process herself. Though each plate took hours to produce, she was at least in creative control.

From “Orlando keeps a dog”, 1948, Hale’s favourite of the series. Her drawings always have such wit. Note Tinkle at the end, causing mischief as always, the cat Kathleen Hale felt was most like her. I love how Orlando wears his watch, their affectionately intertwined tails and Grace’s leopard skin coat.

The books are full of wit, whimsy and delightful visual jokes . They capture the character and grace of cats like no other artist and the text and images are beautifully integrated so as to lead the reader’s eyes dancing around the page. I never knew of her books as a child, and only came across her work when I had my own fine ginger cat, Alan.

One of the reasons that cats are so difficult to draw is that they appear to be boneless, fluid, without any basic structure - round in a round basket, square in a square box, or stretched out like a piece of elastic to twice their normal length.

She said that in writing these books she had a “subconscious desire to create for myself the united family that, after the death of my father and the separation from my mother, I had never had…” In these pages she captures a sense of warmth and security, as Orlando patiently tends to his handful of kittens, alongside his “dear wife” Grace, but they are never sentimental. Seventeen books followed, the last published in 1972.

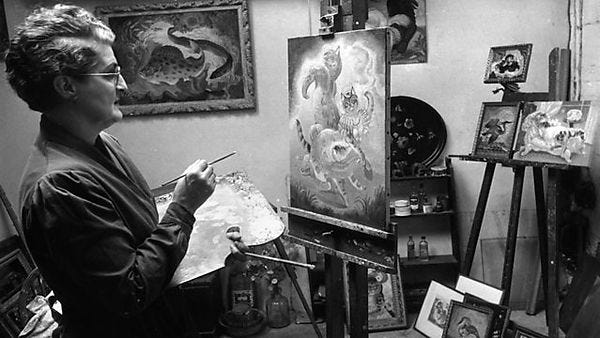

In 1998, at the age of 97, Kathleen Hale decided to sell the contents of her studio, not wishing to burden her sons with sorting out her affairs, she was also fearful of the possibility of paying for going into care, her decision being practical as well as considerate. She hinted at the end of her life that she resented the success of the “Orlando” books, that her work as an illustrator had meant that she had not been able to pursue her work as a serious painter. But the books are an extraordinary legacy. In her enchanting autobiography, “A Slender Reputation”* Orlando doesn’t appear until the last quarter of the book, such were her adventures prior to their publication, and I have only touched on her many exploits and the writers and artists who passed through her life. No matter what life threw at her, she faced it with humour and optimism, always resourceful and clearly enriching the lives of all who knew her.

*The title comes from a remark by Cedric Morris about the books, “Do you mean to tell me, Kathleen, that you hung your slender reputation on the broad shoulders of a eunach cat?”

Kathleen Hale at her easel ©Michael Parkin Fine Art

Something to read

Earth and Heaven - Sue Gee Another wonderful book by this much neglected writer. It is the perfect companion to Kathleen Hale’s story as it is begins at the Slade School of Art at the time she would have been a student at Reading. It tells of a young artist, first against the backdrop of dingy London, described in Sickert’s muted palette, to the lush Kentish countryside, where he begins to raise a family. Gee writes with extraordinary insight into the experience of being a painter and her descriptions of the shifting seasons are luminous. If you read it, do let me know.

Something to listen to

Desert Island Discs, Kathleen Hale Recorded in 1998, at the age of 96, there is no sense that her zest for life had dimmed in the slightest. She takes no nonsense and her candour and impishness make joyous listening.

Thank you very much for joining me this month. Did any of you read Orlando as a child? I would love to hear from you if you did, or just drop me a message to say hello, it is always lovely to receive your comments. My posts remain free, but my subscriptions are open, or you could consider buying me a coffee, as it would really help keep me going here. As always, please press the “heart” if you enjoyed this post! I look forward to seeing you again in a couple of weeks.

Further Reading

A Slender Reputation: An Autobiography, Kathleen Hale

A Lesson in Art and Life: The Colourful World of Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines , Hugh St. Clair

Thank you so much for this wonderful account. Like others, I didn’t own any Orlando books but my husband says he remembers having the stories read to him in the 1940s when they were still quite new. From somewhere in the depths of my memory came a recollection from many years ago, in the early 1970s, of being in a cottage in a room where Orlando books were on display and an old lady was talking about them to another visitor. It must have been an Oxford art week or perhaps even a village gardens open event but I remember that the old lady was Kathleen Hale and it was her cottage, Tod House in Forest Hill outside the city. Apparently she used the village in illustrations in some of her books. I wish I could remember now what she said!

That was lovely! It's so good to read about this talented artist whose books I adored as a child in the mid 1950s. I still have the huge one about Orlando getting a large poodle, it was the biggest book I possessed and the story with the enchanting pictures made me giggle. But something else I loved about them, even as a 6 year old, was the landscapes - the trees were characters, though still realistic and she could paint fields and lanes that I felt I knew; snow scenes in the countryside were magical - and all the different sized pawprints! I must visit my archive in the loft and bury myself in their vivid charm again! Her unconventional (for the time) life sounds challenging but very rich; thank you for writing about her.