Attuned to beauty

The life and work of the artist Jean Cooke, the pleasure of pen and ink and grebe watching

If your mind is attuned to beauty, you find beauty in everything

- Jean Cooke

A few weeks ago I visited The Garden Museum in Lambeth, to see paintings of the artist plantsman John Morley, a collector of snowdrops and friend of Cedric Morris, his Suffolk neighbour.

The work was exquisite: soft, tonal painting of gems from his garden, of auriculas and fritillaries, in aged terracotta pots. But while I admired this work, I found there was little I wanted to say about it. Though very beautiful, my attention alighted instead on a large painting by Morris, placed among them, of a huge, glaucous cabbage filling the picture space. It was exuberant and unexpected among the delicacy of Morley’s work and I loved it. It was painted with thick, oily strokes and made me fizz with delight.

Three Auriculas, John Morley, oil on board

Cabbage, Cedric Morris, oil on canvas, 1956 ©The Garden Museum

But it was what I saw next, just as I was about to leave, that really gave me a thrill. Entitled, “The Garden”, this was not a tamed, formal space, but a peek over a rickety panelled fence into an unruly garden, a magnolia pushing its way through the thicket. It is early spring, and the lime flushed buds are about to burst against the dun branches of winter. I loved the rhythm of the sweeping tangle and the strokes of white that sparked upwards, like fireworks, against the dark. I was enchanted. I wanted to clamber over that fence and see what lay sleeping. Perhaps a robin might lead the way?

The Garden, oil on canvas, c.1992 60.5 x 60.5cm © The Garden Museum

My thoughts were shaken by the caption at its side. It described the painting, by the artist Jean Cooke (1927 - 2008), but went on to say, “In 1953 Cooke had married fellow artist John Bratby, but their marriage wasn’t a happy one. In 1960 the couple had settled in Blackheath and at Bratby’s insistence, Cooke was only permitted to work between nine and midday, initially in a room where the ceiling was collapsing. Bratby would often forbid Cooke to leave the house. Her four children, home interiors, views of the street and the large unkempt garden became recurring subjects of her work”.

Since then, both the image and the caption have haunted me, and I knew I had to follow the crumbs to find out more.

Jean Cooke came late to painting in her studies. As a child she had modelled heads and figures in plasticine, in her teens she had wanted to be an architect and then unable to decide on a discipline at the Central School of Art and Design, where she studied from 1943 - 1945, she chose book illustration, textile and fashion design and history of fashion. It seems she was talented enough to have chosen any of them and been a success, but her course was shifted again following an altercation with a visitor to the school:

Some famous lady said to me that I was the wrong shape to do fashion. I was the same shape she was. I was a little fat girl and she a little fat lady.

I long to know who this famous lady was.

She gravitated towards the Life Room, where her headmistress had warned her that under no circumstances was she to go. Taught by Bernard Meninsky, who said “lovely things” about her work, this nascent talent had to wait, as instead when her grant ran out, she moved to study pottery at Camberwell School of Art (from 1945-8) and then on to train as an art teacher at Goldsmith’s College.

But rather than teach, she established a kiln at Seaford, East Sussex, making up to 50 pots a day. To augment this income she picked winkles from the beach, collected mushrooms and scrubbed floors. Though she enjoyed the physical nature of the work, the endless churning out of pots and the lack of intellectual stimulation, made the appeal of this activity pall too.

It was at this time that she met John Bratby (1928-92) and following a whirlwind romance, she married him in the spring of 1953. He was the great rising star of the Royal Academy, about to have his first exhibition at the Beaux Arts Gallery in Mayfair, and Jean was swept along. Pottery was quickly abandoned and she instead started a postgraduate degree in painting, also at the Royal Academy, as Bratby did not want a potter as his wife.

The jazz musician Brian Innes, along with his partner Marion Platt, shared a house with the Bratbys early in their marriage. He remembers John as a “bulky man”, but his description of Jean is chilling: “Jean, as now, was a dumpily-dressed girl with long, lanky hair and a prematurely haggard face from which two pale eyes gazed out fearfully”. Her tutor, Carel Weight, said in a 1984 interview that Bratby would “lock his wife up whenever he went out, as he felt sure she would escape”1 and though Weight was very kind and supportive towards Cooke in many ways, when she did try to leave, he always encouraged her to return.

Out the Back and Pussy Cat (1964), Jean Cooke. © The artist’s estate, courtesy Piano Nobile

In 1960, Jean and John moved to their first home in Blackheath. With a quarter of an acre of land, John wanted to create a formal garden, but seemingly had little talent at gardening. Their son, David, said his efforts were “dreadful”, and Jean took the reins, allowing the plants to spread and grow wild, with paths that cut through and where the buttercups were allowed to flourish, creating a golden haze in the turf.

Jean Cooke painting in her garden, 1990s, photographed by Linda Sole © Linda Sole

Alongside the garden, raising four young children and taking the role of Bratby’s business manager, she somehow managed to continue to paint in her three allotted hours. She told her friend, the writer Nell Dunn, that, “When the kids were small I went through a thing of never tidying up. I thought rubbish can only get to a certain point and then it will fall down. And during that period I got a lot of painting done”.

Seemingly deeply insecure, Bratby, not only relied upon her to the run the household, but also required her constant reassurance concerning his own work. One of the most shocking facts to emerge was that not content with limiting her work time, he would appropriate her canvases to paint over if needed, hiding others in a cupboard or even slashing them.

Alongside her paintings of still lives and garden views, she made a series of self- portraits. Friends told her that in his portraits of her, Bratby made her look “so old” and as a riposte, she painted herself, “the way I wanted to be seen, or tried to.” These searing images reveal the strain of those years.

Self-portrait, 1959, oil on canvas, 114.9 cm× 83.8cm © Estate of Jean Cooke and The Tate Gallery.

Painted in front of a large oval mirror, it is as though she is trapped within the frame. Her expression is taut, her gaze somewhat fearful. She paints, not in a studio, but in the corner of a bedroom, with a child’s cot behind her. (It was in fact the room that Bratby considered too dangerous to sleep in, as the ceiling was falling down.) While she was painting it, her toddler son, David, picked up her brushes and began making marks, but rather than paint over them, she allowed them to stay. But the unspoken horror, is her black eye. It is one of two self-portraits where this is evident.

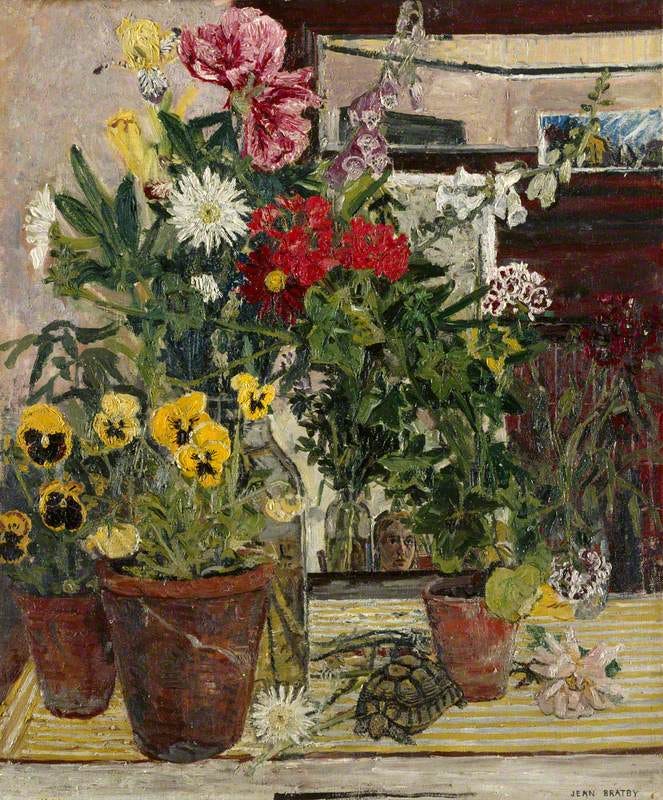

A rather different self-portrait is “Through the Looking Glass,” painted a year later. Her brushwork is robust, and I was reminded of Morris’s thick, impasto style, but there the comparison ends. We see terracotta pots of pansies and Sweet Williams with a vase behind containing a jumble of lilting foxgloves, iris and asters. Was this a hastily arranged still life due to the constrictions of time? A couple have fallen astray on the mantlepiece that lay alongside a tortoise, who had belonged to her neighbour and had happened to wander into her garden one day. But it might also be a reference to the artist who said in 1979:

I am very dependent on nature and the things around me. Each winter I hibernate and then with the first sun, like an old tortoise, I amble out with bleary eyes and start to see again.

Through the Looking Glass, oil on canvas, 60.8cm x 50.8cm © Royal Academy of Arts

For above the tortoise, there is a tiny self-portrait, peering out from amongst the flowers. Note that her signature is “Bratby” and not “Cooke” which he insisted that she use as “she belonged to him”.

Portrait of John Bratby, 1956, oil on canvas, 61 x 50.8 cm © The Estate of Jean Cooke Cooke states that, “I was terrified of him, we all were” and that he had something of the “Bluebeard” in him. His suspicious

All of this makes uncomfortable reading, I know. I was shocked to discover that she stayed with Bratby for 25 years, and after their separation he couldn’t relinquish his hold, phoning her constantly. In an interview with the Daily Mail, he declared, “I talk to her only about the children and the garden”. But such matters are never simple. Carolyn Trant says that, “the real tragedy was that she genuinely loved her husband”.2

In spite of the hideous constraints, she produced some remarkable works during her marriage and it is important to recognise the positives that emerged from this relationship. She said that looking after his work made her feel “trusted and indispensable.”3 The daily three hour painting time forced her to focus and she said she needed “resistance” to complete work, something to fight against, and their relationship provided that. In addition to everything else, she taught at the Royal College as a lecturer in painting from 1964 to 1974, was elected as associate of the Royal Academy in 1965 and became a full Academician in 1972 - all remarkable achievements.

Learning of what she endured within the marriage, initially coloured and overshadowed the impression her painting made on me that day, but seeing this remarkable short film of her below, shifted my focus back. You see what is a tiny, impish woman who is utterly captivating. She is delightful and funny, a good mimic and must have been wonderful company, and though told in a light-hearted way, what she says of Bratby’s behaviour is deeply unsettling and leaves us in no doubt of how hard it must have been.

In the last years of her life, she split her time between a rented coastguard cottage at Birling Gap and her house at Blackheath. One provided air and space, the other a sense of immersion. She outlived Bratby by several years, her paintings becoming sparer and more distilled as time progressed, creating a number of seascapes and Japanesque irises in watercolour . Although oil remained her principal medium, I love the space and simplicity of these works. Of watercolour she noted,

You have to have a very taut brush that doesn’t sag on you. It’s like walking a tight rope , you can fall off so easily.

Iris, watercolour on paper, 1981, 37.7 x 27.9 cm

But those last years were not altogether peaceful. Her cottage at Birling Gap had to be demolished in 1995 due to coastal erosion, but unvanquished she moved into the next one along, stating, “that will see me out”. And then her home at Blackheath was razed to the ground by a terrible blaze. Her son, David, managed to rescue many of her paintings along with some of her paints and favoured brushes, but the land on which the house stood was redeveloped and the garden lost.

Jean Cooke died a year later, found in her armchair, looking out to sea at her beloved Birling cottage.

Of all the painters I have explored, she is the one I would most like to have met and who certainly deserves to be better known. Her resolve, her resilience and determination to continue to push forward in her painting is remarkable and she seemed such fun. After Bratby left, at the age of 47 fell in love with a 19 year old Argentinian and they planned to sail around the world together, in a boat called Crazy Blue. Sadly, the adventure didn’t happen. Asked if she had any regrets, she said,

My only regrets are that I have not painted things and people that I thought would be there forever…Even the springtime goes too fast, and each year I write in my diary to ‘be ready for the cherry blossom’. I haven’t painted it yet. Tomorrow is it going to snow? Am I ready for it?

The Wild Plum Tree, 1995, oil on canvas, 50 x 40 inches

The Birth of Icarus, oil on canvas, 1998, Private Collection This shows magnolia blossom at night, “the petals were dropping down like wings”.

Thank you very much for spending time here this week and I look forward to hearing your thoughts about Jean Cooke, or indeed about anything else in the post. If you are able to, please consider subscribing and do press the heart to let me know you have visited and help share my work. I look forward to seeing you again in a couple of weeks.

Something to draw

Over the past few days, I have been sitting in the garden, drawing again - using a dip pen and ink and wash - just getting used to looking again and trying not to dwell on detail. Using pen and ink forces you to fuss less - you make a line and you have to stick with it. It makes you commit and focus, but most importantly it makes you let go. You can’t go back, if you make a blot or mistake, that becomes part of the life of the drawing. If you haven’t yet tried, pick up a sketchbook, and get dipping.

From the garden

One nest ends and another begins. Having lived with this garden for 25 years, I know where to look for nests - Great Tits nest in the bowl of the apple treee, and the Blue Tits chose same flat each year in the nest box and now are just about to fledge. I sat and watched their endless comings and goings and managed a couple of snaps.

But it is the Great Crested grebes that are the most anticipated. This year they have built a nest just a few feet away from the garden’s edge and so I can sit and watch and record their activity with my camera. The high water levels over winter have washed away much of the plantlife, and the eggs are precariously placed and vulnerable to storms or sudden rising water. Last year the first two attempts failed, it was heart breaking to watch, but they succceeded late in the summer with two fledglings. I will report back.

The male Grebe is bringing a rather unweildy stick to add to the nest.

My linoprint of the Great Crested Grebe sitting on her nest from a previous year’s watching.

Something to watch

There are two excellent films about women artists currently on i-Player. The first Painting the Line charts the work of Bridget Riley through a series of interviews filmed over her career, led by the unestimable Kirsty Wark. The second I am the Sixties covers the life and work of one of the founders of Pop Art, Pauline Boty, who tragically died at the age of 28. I knew little about her before this and this is a must see.

If you liked Cedric Morris’s Cabbage, here is a little film from Philip Mould about why his exuberant still lives make him smile too. You can see my previous post here on Morris (that I have opened up for this) about why I love his work too.

Something to read

I have returned to a favourite comfort author this week, Mary Stewart, and have been romping through “Nine Coaches Waiting”, a brilliant pageturner that I gulped down all too quickly.

While I am not usually fond of historical fiction, I thoroughly enjoyed “Earthly Joys” and its sequel “Virgin Earth” by Philippa Gregory. They tell of the Tradescants: John, creator of Hatfield House Garden and gardener to Charles 1; and the Younger, who is buried in an ornate tomb, at The Garden Museum, who travelled to America to collect plant specimens and succeeded his father as Royal Gardener. They both provide a fascinating glimpse into the history of plants and gardens.

Tradescant the Elder, Unknown artist, The Garden Museum

Further Reading

Seeing Ourselves: Women’s Self Portraits - Frances Borzello

Jean Cooke- Ungardening - Andrew Lambirth, The Garden Museum

Jean Cooke: A Reputation Reassessed - Andrew Lambirth, Piano Nobile

Tate Women Artists - Alicia Foster

The Story of Art - Katy Hessel

Voyaging Out: British Women Artists from Suffrage to the Sixties - Carolyn Trant

In the looking glass : an exhibition of contemporary self-portraits by women artists, 1996, The Usher Gallery, Lincoln

From “Ungardened,” Andrew Lambirth.

From, “Voyaging Out”, Carolyn Trant.

From “Ungardened,” Andrew Lambirth.

This was shocking. Jean Cooke's art is beautiful. I also clicked through to the Guardian article and was shocked again that his second relationship "muse" stayed with him. I'm coming to distrust men who have a muse. It usually involves control. My ex brother in law insisted that his new wife didn't work once they were married. This was the mid 1980s for heaven's sake! She was a highly trained nursing sister. He was in the merchant navy and away for weeks at a time. I remember going to visit her for the first time with my new husband, her brother. She was sitting in this pin-neat modern house, with a neat garden, just whiling away time. I just couldn't get my head around it. I have to admit I disliked the brother in law intensely and viscerally the first time I met him, and he also felt the same about me because I must have been giving off strong vibes of "I wouldn't stand for this shit". Thankfully they are now divorced, at her instigation, but what a waste of a life.

Oh my, how sad for her, but what a remarkable artist she was! This is a lovely post. To follow up, I just read the Painters of Today book about John (available on the Internet Archive), which was published in 1961. This provides a descriptive biography of sorts about him, his art and his writing (followed by a number of his pictures), and I kept reading looking for the author to mention Jean Cooke and her art (which in my opinion is much better than his!), but there was no mention of her by name (that I could see), other than being called ‘the wife’ on p.20… I’m glad that she is getting the recognition she deserves now.