How one thing leads to another

From Eve Garnett to "Carnation, Lily, Lily Rose" and on to Barbara Comyn's "Sisters by a River"

Eve Garnett and “The Family from One End Street”

The writer and illustrator Eve Garnett is an anomaly among those I have already covered. I hadn’t read her as a child, knew little of her until very recently and confess I had preconceptions about the book that were totally unjustifiable. I had recently bought a copy in a charity shop, which had piqued my interest, but the book kept appearing in my reading and in various guises here1. It was as though it was vying for attention, saying “Look at me, look at me!”, until I could resist no longer. What I discovered sent me down endless literary rabbit holes, until I finally had to come up for air and get on with the post. But I am very glad I listened to the call.

Eve was born in Worcestershire in 1900 into the illustrious literary Garnett clan: her aunt was Constance, the translator of Chekhov and Dostoevsky and her cousin David, was the novelist, publisher and husband of Vanessa Bell’s daughter Angelica. It was an idyllic, middle-class upbringing in which she was shielded from the realities of urban poverty. An artist, before she was a writer, Eve trained at the Chelsea Polytechnic School of Art and then the Royal Academy. But it was during this time as a student in London that her eyes were opened to an alternate world. When walking the streets looking for subjects to sketch, she was “appalled by the conditions prevailing in the poorer quarters of the world’s richest city” and began filling her sketchbooks with studies of the children she saw.

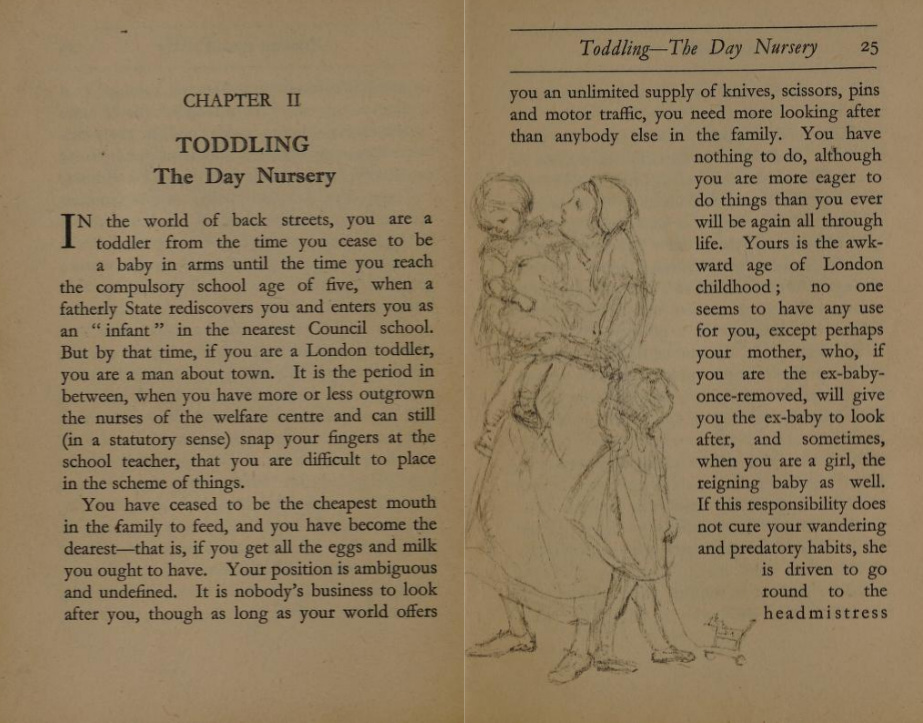

Her work had already attracted the attention of the publisher John Lane, creator of the periodical “The Yellow Book”, who, on seeing these drawings, gave Eve her first commission: to illustrate “The London Child,” a clear sighted and touching text by the writer and suffragist Evelyn Sharp, describing the lives of the working class poor in 1927. Her fluid and expressive drawings are a strong support, but Eve, haunted by what she had seen, wanted to develop something of her own to “publicise the conditions poor children were living in.”

From “A London Child” showing drawings of a very different style to those that appeared in “One End Street”

She initially intended to write for adults, but publishers would only accept the book if it was aimed at children. She reworked it, endured countless rejections, but finally found acceptance with Frederick Muller.

The origins of this book suggest that it might prove worthy reading, but what emerged was a portrait that gave working class children a voice that was groundbreaking in its honesty, yet utterly charming.

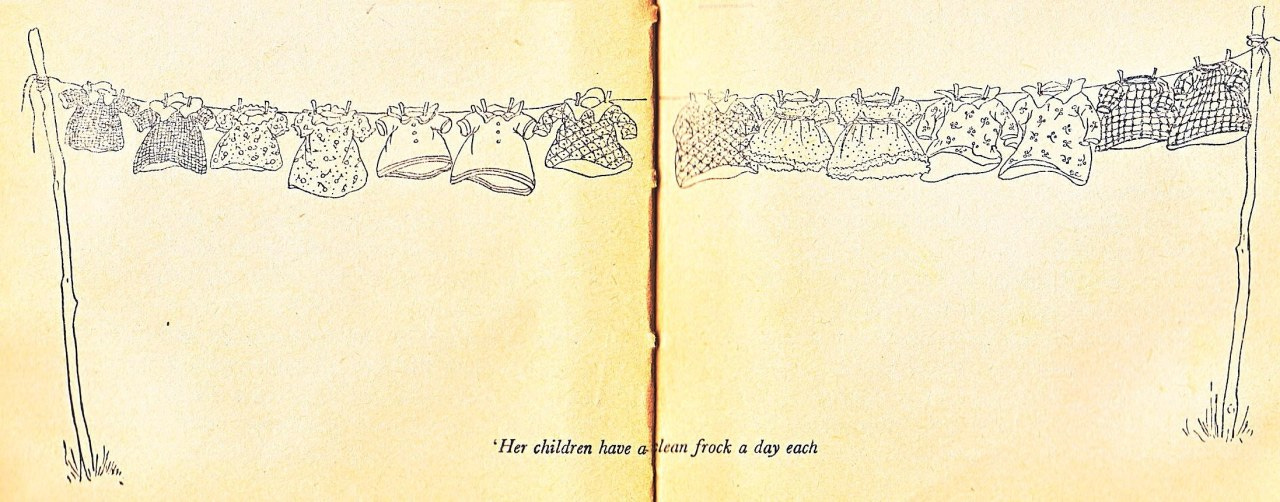

I loved this double page spread illustration displaying the washing of the Beaseley family who could afford to wear “a frock a day”

It tells of the Ruggles family: father Jo, a dustman, mother Rosie, a washerwoman and their seven children. There is no plot as such, but a series of episodes, that tells of their adventures, beginning with the story of how their first born child was named. On a visit to the Tate Gallery, they pause in front of Sargent’s “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose.” There is much tut-tutting about the chink of Jo’s steel shoe tips (a sign of his poverty) from their fellow middle-class gallery-goers, but they declare the painting, “lovely” and later Rosie decides “Lily Rose” the perfect name.

The lack of money is a constant undercurrent: Kate is the first in her family to pass the 11+, but soon the fear of how her uniform will be paid for arises and doubt builds as to whether she will be able to go after all; when the twins are born, Jo has to go to the Vicarage for their “kind assistance” as only one child had been expected; and while attending the church Harvest festival, the sight of the produce alerts Jo to how they could produce more food and he ponders where to put a pig pen.

But this is lightly done, and on each occasion their tribulations are met with a Blitz spirit, with kindness and friendship and the certainty that all will end happily. Poverty is presented as a fact of life: there is no resentment or bitterness. This, sadly, led to the book being criticised in the 1960s as patronising towards the poor, with some arguing that Eve Garnett was an outsider looking in on the suffering caused by hardship. But this denies the context in which it was written. Children’s books during the 1930’s were dominated by the middle classes and this was the first that presented the working class with dignity and decency, acknowledging their struggles but doing so with charm and humour.

Her illustrations too are lovely. Simple line drawings, in pen and ink, that look back to Kate Greenaway, but instead of quaintness, we have real, untidy children that tumble and get into scrapes. Their social situation is clear in the “happy snap” of the front page, but we also see a family bound by love and affection. They are characters we wholeheartedly believe in.

“A happy snap at No1 One End Street” showing Jo, Rosie and the 7 Ruggles children

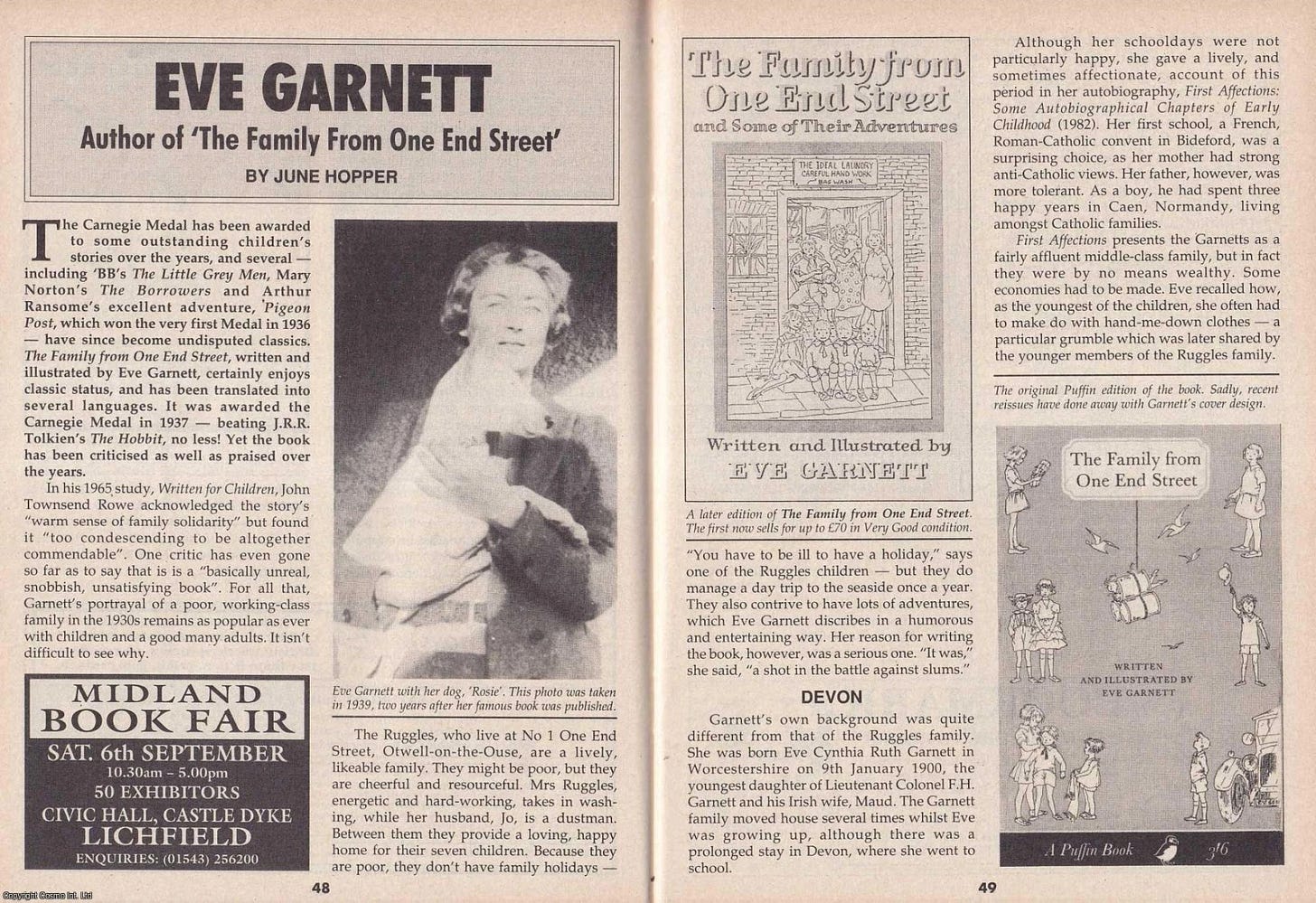

The book is enchanting and how refreshing it would have been to have met the sparky, good-hearted Kate instead of the cosy inhabitants of Enid Blyton that appeared in my stocking. It was awarded the second Carnegie Medal in 1937, triumphing over “The Hobbit,” and was later serialised in 1939 on BBC Radio’s Children’s Hour—an ideal antidote to the mounting fear on the cusp of World War II. In fact, it is the perfect book to read again now - I can guarantee it will bring cheer.

An article from 1939 that coincided with its serialisation on radio.

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose

This leads me to the painting that sets the Ruggles’ story in motion - Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose. As a student, it was a particular favourite at the Tate, and I would sit gazing at it, bathed in its apricot light.

John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), Oil paint on canvas, 1885 - 1886, 2185 x 1970 x 130 mm Copyright The Tate Gallery

It was painted at a time of crisis for Sargent. His painting “Madame X” had caused outrage for its provocative bare shoulder, with slipping strap, and he left Paris for London, his reputation in tatters. A year later, while on a boat trip down the Thames, near Pangbourne, he saw the riverbank lit by Chinese lanterns and an idea took root.

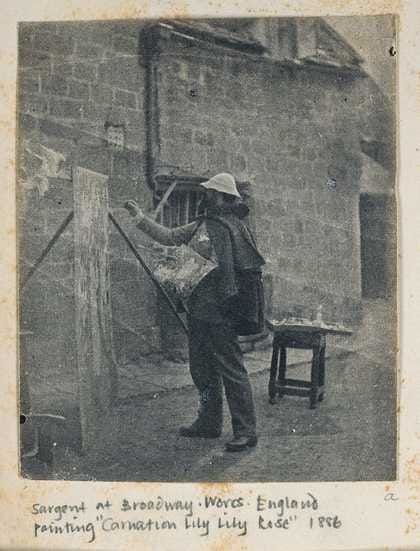

The painting began while Sargent was staying with his friend, the artist FB Millet at Broadway in Worcestershire. The original model was Millet’s five year old daughter, Kate, but he decided her hair was too dark and she was replaced, much to her consternation, by the daughters of the illustrator Frederick Barnard: Polly, aged 7, and Dorothy, aged 11.

It combines the romantic aestheticism of the Pre-Raphaelites with the en plein air technique learned from his friend Monet. Each evening he would set up his easel and paints, in readiness for the brief window of fading light. His friend, the writer Edmund Gosse, describes how:

"…at a certain notation of the light [he] ran forward over the lawn with the action of a wag-tail, planting at the same time, rapid dabs of paint on the picture, and then retiring again, only, with equal suddenness, to repeat the wag-tail action. All this occupied by two or three minutes, the light rapidly declining, and then…Sargent would join us again…in a last turn at lawn tennis.” Edmund Gosse

Photograph of John Singer Sargent painting “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose” at Broadway in Worcestershire, 1856 Harvard Art Museum/Fogg Museum, © President and Fellows of Harvard College

This process continued over two late summers, from September to early November. When the flowers faded, they were replaced with artificial ones to maintain the composition.

It is this sense of urgency that elevates the work from one that could have been replicated in a studio setting: the gestural brushstrokes have energy and life as he worked to capture the evanescence of dusk and the end of summer days. He complained in letters to friends of the subject’s difficulty, but each evening he persisted, finally completing the work in October, 1886.

I love the girls’ absorption as they carefully light the candles within the lanterns and the sense of immersion in the tangle of leggy carnations and shell pink roses. The rosy sky can’t be seen about the towering lilies, but you feel its glow. As we slip into autumn, it is the ideal evocation of summer’s closing days.

The title of the piece comes from a popular song at the time, “The Wreath”, by the 18th century composer Mazzinghi, that Sargent and his friends would play around the piano. In case you, like me, are curious to hear what it sounds like, I found this (it begins 3.55 minutes in!)

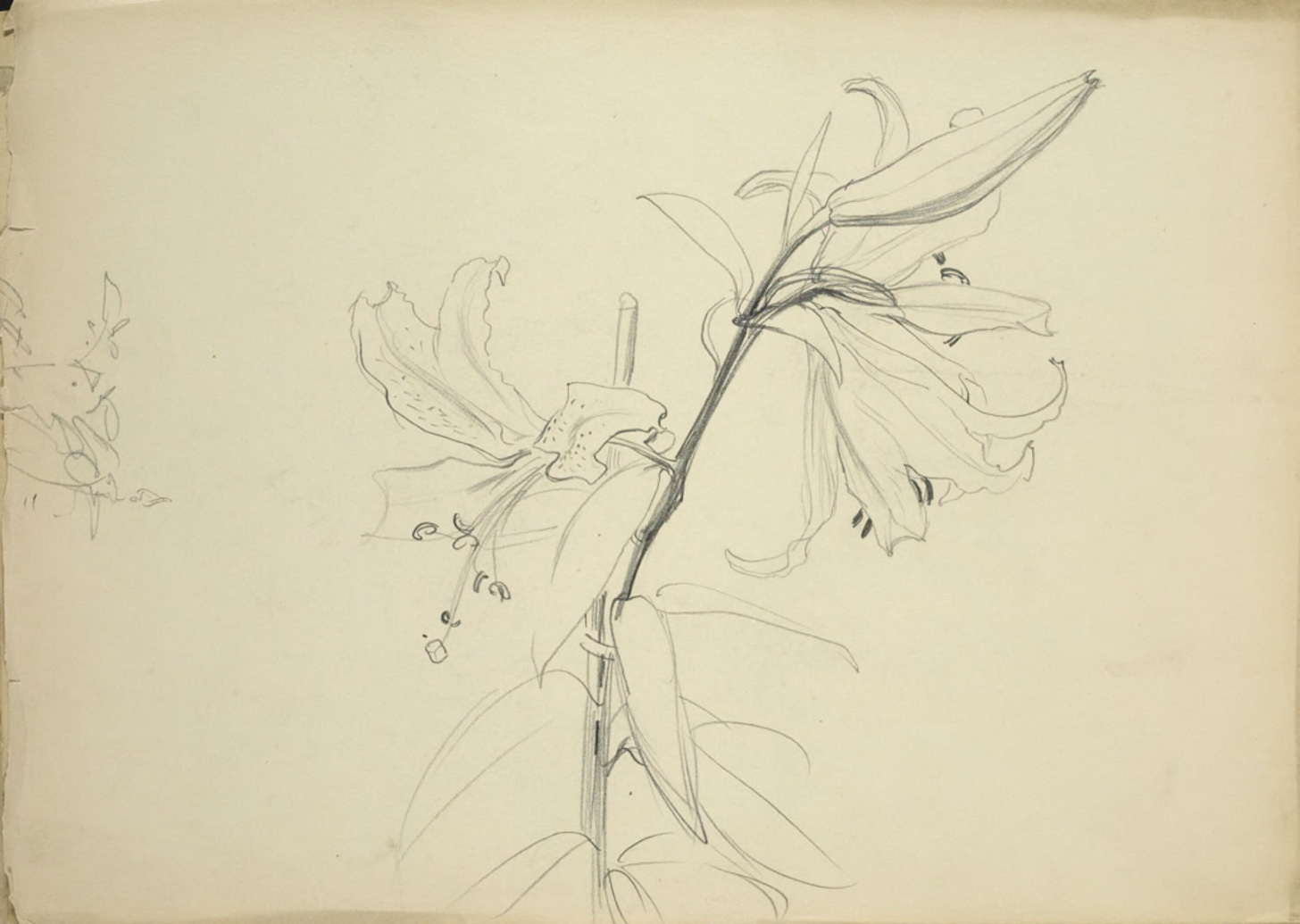

Study in pencil for “Carnation, Lily, Lily Rose” © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Study in pencil for “Carnation, Lily, Lily Rose” of Polly Barnard c.1887. I love the firm, strong line delineating her profile ©Tate Gallery

The companion pencil study of Dorothy ©Tate Gallery It is likely that these studies were made as presentation studies, rather than preliminary sketches, and they were bequeathed to the Tate in 1949.

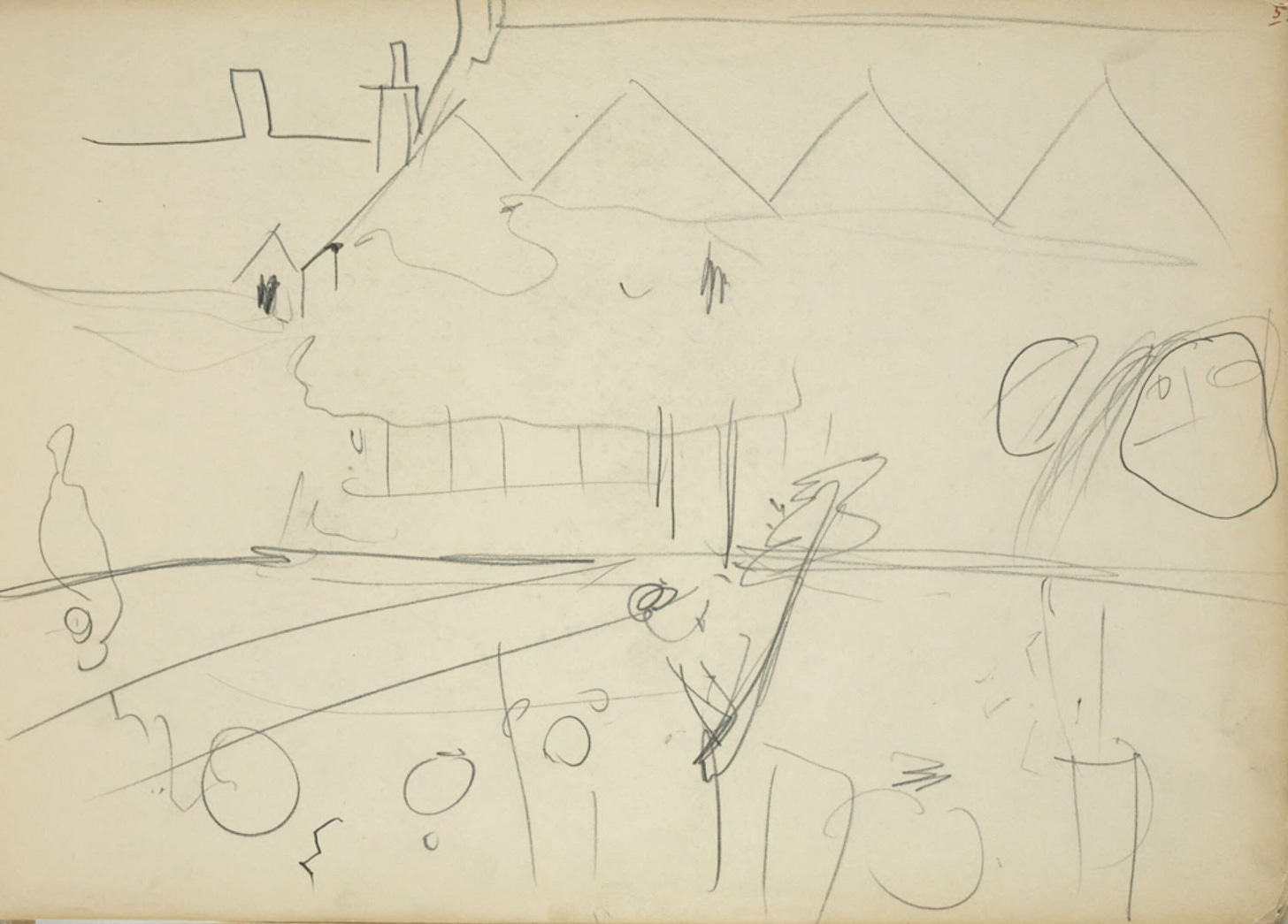

A sketchbook page study for the painting in pencil 24.7 x 34.6 cm. I find this fascinating - we see here Sargent thinking through the composition Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College

John Singer Sargent, a Study for “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose” 1885, oil paint on canvas, 59.7 × 49.5 cm from a Private collection

Sisters by a River by Barbara Comyns

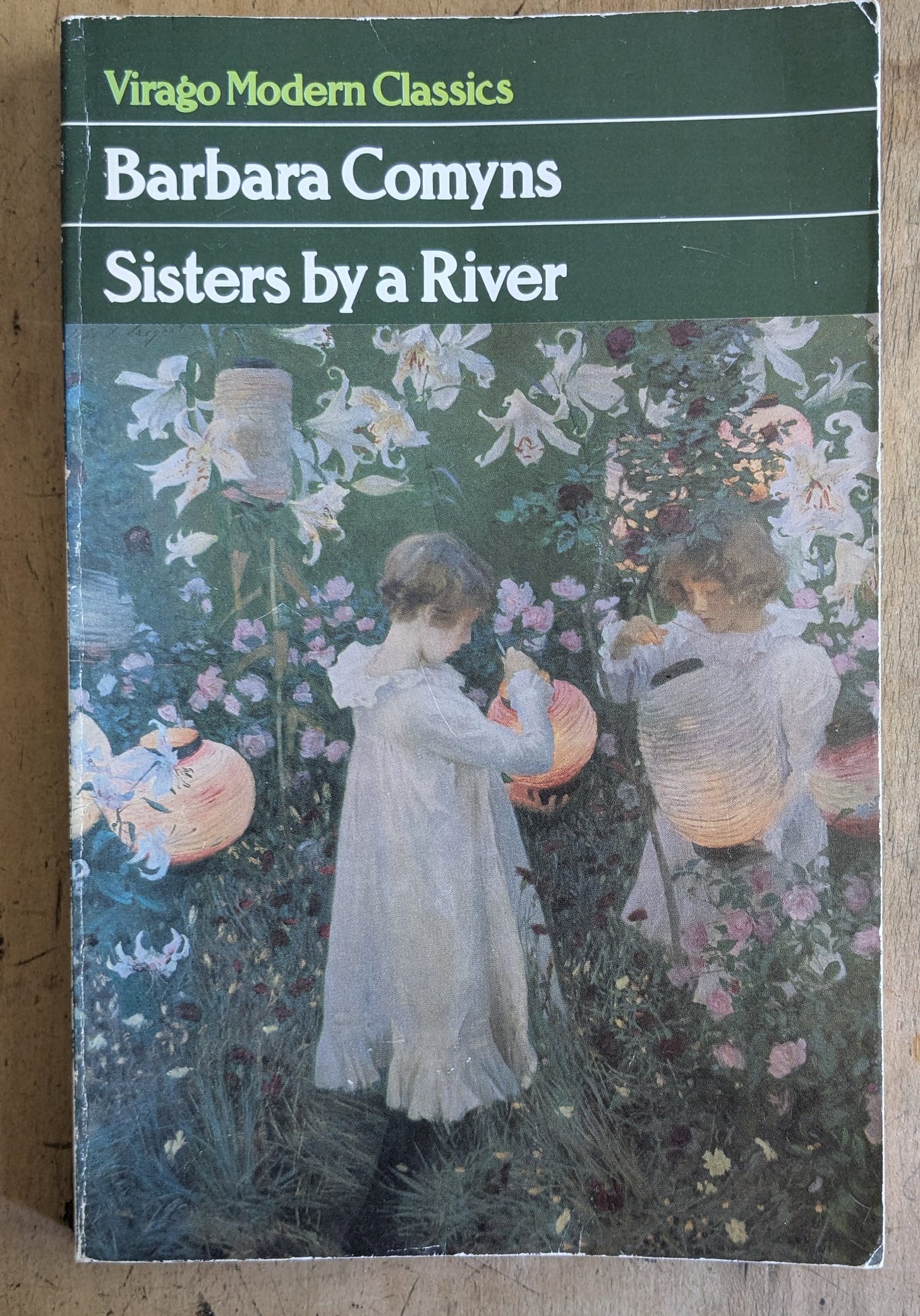

And on to “Sisters by a River,” by Barbara Comyns, a book I chose entirely for its cover, when spending my first wages. Virago’s were always at the top of my list, and I remember this followed my purchase of Elizabeth Taylor’s “Angel” - it seems I chose well, though I knew nothing of either author, making my choice purely based on their delectable covers.

This dreamlike, alluring painting is, in fact, an odd cover choice for a book that is far from serene: you can’t imagine these feral children in such pristine white dresses. Like all Comyns’ novels, it is impossible to define. It was written in 1941, with the intention of amusing her children with the story of her childhood, though I am unsure that being amused is quite how they would have felt. It remained in a suitacase for two years, until a friend discovered it and encouraged Barbara to try to publish it.

It tells of a violent, drunken father, a deaf mother and their seven children - a family who couldn’t be more different from the benign Ruggles. It is also episodically structured, narrated by the author with an odd sense of detachment. While the events are recalled years after, the language is that of a child, with erratic spelling and phrasing. This childlike perspective allows us to view their lives with only partial understanding, but it sharpens our senses to what is really happening.

It is a quixotic mix of charm with unexpected twists of the macabre. The parents are clearly neglectful and the older sister, Mary, rules over her siblings with a rod of iron: Barbara is allowed to wear only brown, or else…

While there is no narrative, there is a sense of time passing and the children growing up. The ramshackle mansion in which they live, which “went back to fifteen something,” slides into decay and the river alongside their home, freezes and thaws. It is never explained how their father earns his money, but it is clear that funds are dwindling, with barely enough to pay the maids.

What makes this so disarming is the matter of factness with which events are relayed. She sees Granny being pushed out of the window, “she was half in and half out…it was really a mercy her hips were so wide and the window rather narrow”. The elderly Miss Vann, one of the endless parade of governesses, who wears “three pairs of knickers by day and five by night”, is pushed down the stairs and lands with her head in a “brass pot”. Mercifully she survives, but soon departs.

All the while I was reading this, the question kept surfacing, “Can this possibly be true?” Who knows, but this strange, rather marvellous, writer is well worth reading.

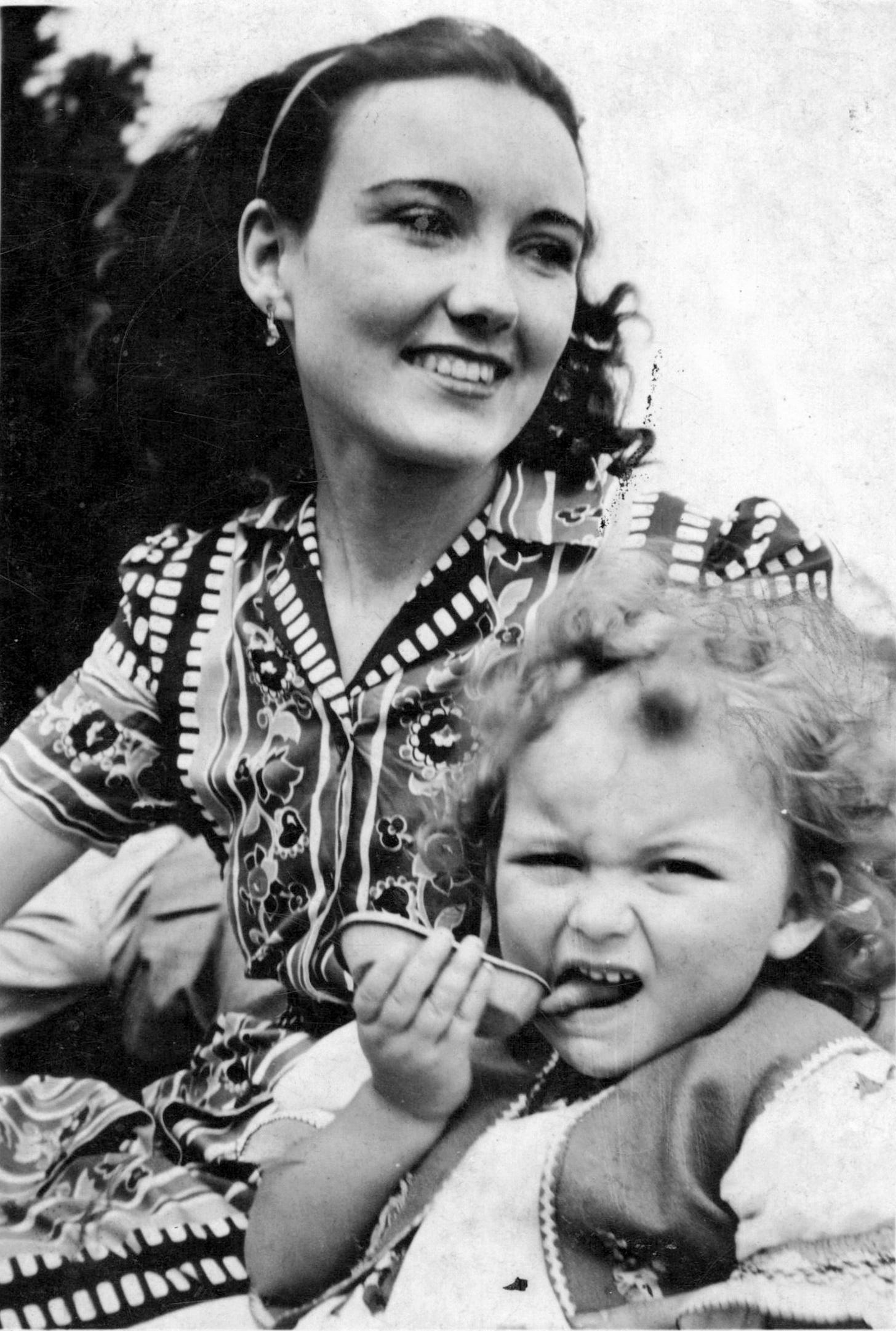

Barbara Comyns and her daughter Caroline in 1938, a year after “Sisters by a River”was published (Manchester University Press)

Something to watch and listen to

If you want to know more about Barbara Comyns listen to this Slightly Foxed podcast.

I also have watched this adaptation of “Tom’s Midnight Garden” from 1989 (very much better than the later ghastly film.)

And I missed hearing this for my last post on Shirley Hughes, an edition of Private Passions, broadcast for her 90th birthday, and thought you might like to catch up too.

And that led me to this treat. For fellow lovers of The Archers this wonderful edition of the programme featuring Carole Boyd, who plays Lynda Snell so beautifully, is a delight.

Something to Read

I have Ronnie from Quiet to thank for this wonderful read: Lucy Mangan’s Bookish: How Reading Shapes our Lives. When she declared,“I am never happier than when I am in a bookshop”, I knew I was in good company. When I got my first job, I remember the thrill of realising that I would now be able to buy a book every week and I have not stopped since. This is a memoir of reading pleasure, taking us on an eclectic, and delightfully unsnobbish, tour of the books that have enriched her life. I found myself noting down books that I have missed, delighting in those I have loved (how I adored Forever Amber) and laughing out loud at her condemnation of Angel Clare (and I never laugh at books.) Thank goodness I still have “Bookworm”, her memoir of childhood reading, still waiting for me.

These posts often lead me on unexpected journeys- this was just one little excursion. Thank you for coming along with me. In the coming weeks I hope to be out with my sketchbook again - I dislike the dregs of August and am very excited to be on the brink of autumn. I look forward to seeing you again in a couple of weeks. As always, your support means a great deal— do drop me a line, I love to hear your thoughts.

Lewes Gasworks from South Street, c.1935–1939, oil on panel, H 13.4 x W 17.2 cm,© the artist's estate. Lewes Castle and Museum Garnett was also a talented painter, exhibiting at the Tate, The Society of Women Artists and the New English Art Club. This is the only work I was able to find.

Further reading

Eve Garnett: Artist, Illustrator, Author - Terence Molloy

The London Child - Evelyn Sharp (available to view on the Internet Archive.)

Unfinished Adventure: Selected Reminiscences from an Englishwoman's Life - Evelyn Sharp

A history of children's book illustration -Tessa Rose Chester and Whalley, Joyce Irene

Thank you especially to E J Barnes from Economical with Fiction whose suggestion led me to Eve Garnett!

![‘Her children have a clean frock a day each.’

Eve Garnett, The Family from One End Street (Harmondsworth: Puffin, 1961[1937]. ‘Her children have a clean frock a day each.’

Eve Garnett, The Family from One End Street (Harmondsworth: Puffin, 1961[1937].](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6ZhT!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0a5fa175-cf2a-49ee-b06d-77e227bd5cb0_969x527.jpeg)

![’Please Mr Ruggles, one o'clock.’

Eve Garnett, The Family from One End Street (Harmondsworth: Puffin, 1961[1937]. ’Please Mr Ruggles, one o'clock.’

Eve Garnett, The Family from One End Street (Harmondsworth: Puffin, 1961[1937].](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Pyxi!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7d2be780-e39c-4a84-9333-0d532c97e05d_1101x557.jpeg)

I remember being entranced by the illustrations in my Puffin copy of The Family from One End Street. My favourite though was Holiday at the Dewdrop Inn. Must excavate them and re-read!

If you liked Bookish, perhaps you'll also like The Child that Books Built, by Francis Spufford. Narnia, Little House on the Prairie, Earthsea...but with a vein of unsentimentality and background family illness to dispel any cosy wallow. The first I've ever encountered anyone else describe the soundless airlock you enter when as a child you become immersed in a book. It continues into adulthood - much to the frustration of my teenage children at the time. "Mum! MUM!!" "Mum's reading again. MUUUUM!!!!"

Oh my goodness! This is wonderful. Between 1987 and 1989 I worked for an American investment bank on the Strand and, if I could get away early enough (sometimes I would take a half day’s leave), I would stop at the Tate on my way home to Clapham Junction and sit and soak in Carnation, Lily, Lily Rose. The light is tremendous and I found it so calming. I think it is still my favourite painting. I used to have a poster of it, but it’s impossible to replicate the feel of the original.

I don’t always comment, but I do so love your writing.x