The smallest things are gifts

Pass time slowly in the delightful company of the painter Mary Newcomb (1922-2008)

I wanted to say these things and to record what I have seen to remind ourselves that - in our haste - in this century - we may not give time to pause and look - and we may pass on our way unheeding. Mary Newcomb

The Waveney Valley, where I live on the border of Norfolk and Suffolk, is an unassuming landscape. In the 1950’s and 60’s ramshackle farmhouses and cottages could be bought here for a song. There remained unkempt corners, mill ponds and sprawling hedgerows - it was the back of beyond and the perfect place to retreat from the ‘madding crowd’. It was to this forgotten corner of England that Mary Newcomb, and her trainee farmer husband, Godfrey, began their married life in 1950. But in this quiet landscape, Mary noticed things that others did not and in so doing captured rural life on the brink of change.

The two had met on a boat trip with the bird painter, Eric Ennion, searching for bitterns in Walberswick. She had been working under Ennion’s tutelage at the Flatford Mill Studies Centre where she learned to how to record and sketch what she saw and to hold it in her memory.

Mary had no formal art education, instead she completed a degree in Natural Sciences at Reading, then taught Maths in Bath High School. In the evenings she had studied at the pioneering Bath Academy of Art, at Corsham Court, run by Rosemary and Clifford Ellis, where she learned pottery. She said she would have loved “to have gone to Art School, but…being wartime it was considered useless to ‘the war effort’”.

The Masham, 1975, oil on board, 50.8 x 50.8 cms Private Collection

But her love of painting was always there, waiting. “At the age of eight or nine…I remember an afternoon when a teacher, looking at our drawings of blackberrries on the wall, saying, ‘That is a good drawing, Mary.’ I said quietly, ‘Yes, I know!’ with a sudden feeling of knowing, and I remember skipping home, then even if life was uneventful, I would always have something or some inner resource to draw on!’1

Then came the move to Suffolk. In their first farm, near Needham Market, Mary and Godfrey set up a pottery, spun wool from their mixed herd of sheep and restored gypsy caravans. It sounds idyllic, but it was jolly hard work keeping it all going. From their pottery, they produced medieval influenced slipware, which was sold in craft shops. This can still apparently be found in local boot fairs, though I have never been lucky enough to spot it!

Sheep Sitting Down , 1994, oil on canvas,106 x 106 cms Private Collection

But her love of painting began to resurface. The pottery became Godrey’s domain and, “when all the animals had been fed, and the children, and the eggs had been washed…” she devoted early mornings, working between five and seven before her daughters went to school, and late in the evening, to her painting.

As her confidence and work grew, exhibiting it at the Norwich Twenty Group, selling them to eagle eyed buyers for £20.00, she decided to test the waters in London. She chose art dealer, Andras Kalman, a Hungarian refugee who had promoted L S Lowry in his first gallery in Manchester. On her first visit, she entered the gallery to find it bustling, and too nervous to make her approach, turned heels, and returned to Norfolk. On her second attempt, she was bolder, and so began the perfect association between gallery and painter. At the Crane Kalman Gallery, she had 12 solo shows from 1970 until the end of her life, and many more in Europe and America. Her work became highly collectable and David Attenborough was one such collector.

He wrote her a fan letter and mentioned two paintings of terns. She had observed these birds, making careful notes, on Southwold Pier. One sat on a pale blue post while the other, rising above it, presented sand eels. He finished his letter saying that what she had seen was a mother feeding her young, and was not a courtship display, as she had suggested. Her forthright response was, “How would he know? He wasn’t there!”2

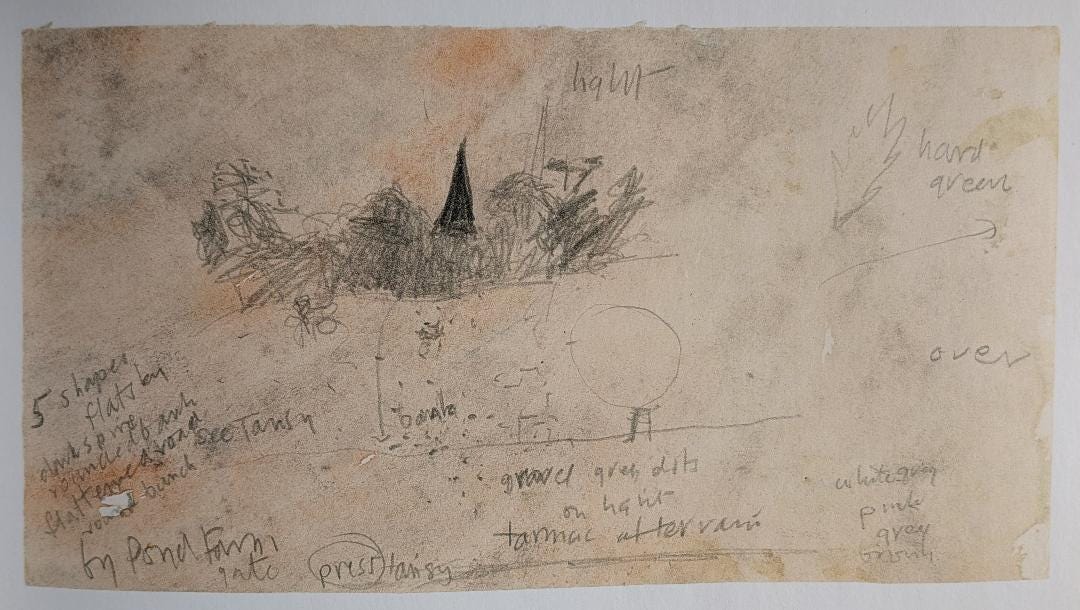

I love the certainty of her response, and how she had a quiet resolution in what she saw and how she painted it. Her painting process was as idiosyncratic as her vision. She didn’t keep a sketchbook to record her observations, but instead made written notes on scraps of paper, seizing the vision, “as they always seem on the verge of disappearance”. These were stored in her studio under various headings: “Bizarre and Jazzy Days”, “Things Bright in the Sky” and the perfectly ‘Mary’ title, “Strange Situations”.

Collared Doves LIfted by Light, 1998, Oil on canvas,63.5 x 58.4 cm Private Collection

Before she began work, she didn’t do warm up drawings as many artists, but instead wrote maxims, almost as if to draw together her thoughts. A particular one, that was ultimately written on her studio wall in large letters was:

Press close to farms, for all your life comes from them.

She would have several works on the go at the same time, and boards would be lined up against the wall in readiness, each painted in colours, often from the remains of the previous day’s work. “I cover them in colour, then paint over that. Sometimes the picture will obliterate the first shades, sometimes, as I paint, the colour will blend beautifully with the background, so it remains”.

Mary Newcomb in her studio, 1994

The paintings emerge slowly, sometimes initial studies are made as shown below in, “The Lady with a Bunch of Sweet Williams” where the image is thought out. Her friend the writer Roger Deakin describes how the process developed:

The impression you often have, looking at one of her paintings, is that ‘Suddenly there it was, and Mary painted it.’ But, in fact, each painting evolves slowly in the studio. Mary paints a first version, blocking out the main elements, then stands it against the wall. Over a period of weeks or months she will then begin to tear out bits of colour or texture that catch her eye in magazines and arrange them on the floor beside each picture. As we move through the house we step carefully around these pools of colour.

At the end of each day’s work Mary also paints out all her brushes on to pieces of hardboard and stands them near the painting in progress. ‘Just now I’m still stuck on green,’ she says. A particular colour will preoccupy her for weeks, and the painting out of the brushes is much more than ‘a good way to use up spare paint’, as she deceptively claims. It is the gradual preparation of the underpainting that gives the pictures such depth and mystery, and often pushes them to the edge of abstraction. Turner did something similar in his ‘colour beginnings’. It is the most profoundly unconscious part of the painting: the music of the song.3

It is a beautiful and telling description of how each work came into being.

As her success grew, Collins notes that she, “remained entirely unaffected, armed with a watchful eye, a rich interior vision and a quiet but resolute determination to paint exactly how and what she wished”. She painted what she loved, there is no sense of her painting for a perceived audience, it is entirely her own vision. She did not trust academic art, she wanted to learn through her own exploration and “to discover things for herself than be taught second hand thoughts”.

Her vision is not one liked by everyone and perhaps that is partly why she remained a partial outsider, maintaining “ a distance around” herself, a quality necessary to create her distinctive paintings. Her work has been called ‘naive’, but I think that this is a misreading. While she played with scale and perspective , it does not mean that she did not understand the rules: she rather used them to draw attention to what she wanted us to notice. She saw things with a freshness, as a child does, and we see the world anew through her eyes. As her friend Ronald Blythe said:

She painted things nobody else saw - small things sometimes…she brought something so simple to painting that no-one had had really even seen before. She points us to things we know all about but haven’t looked at properly. When you look at them, you think, ‘Why didn’t I notice that before?’

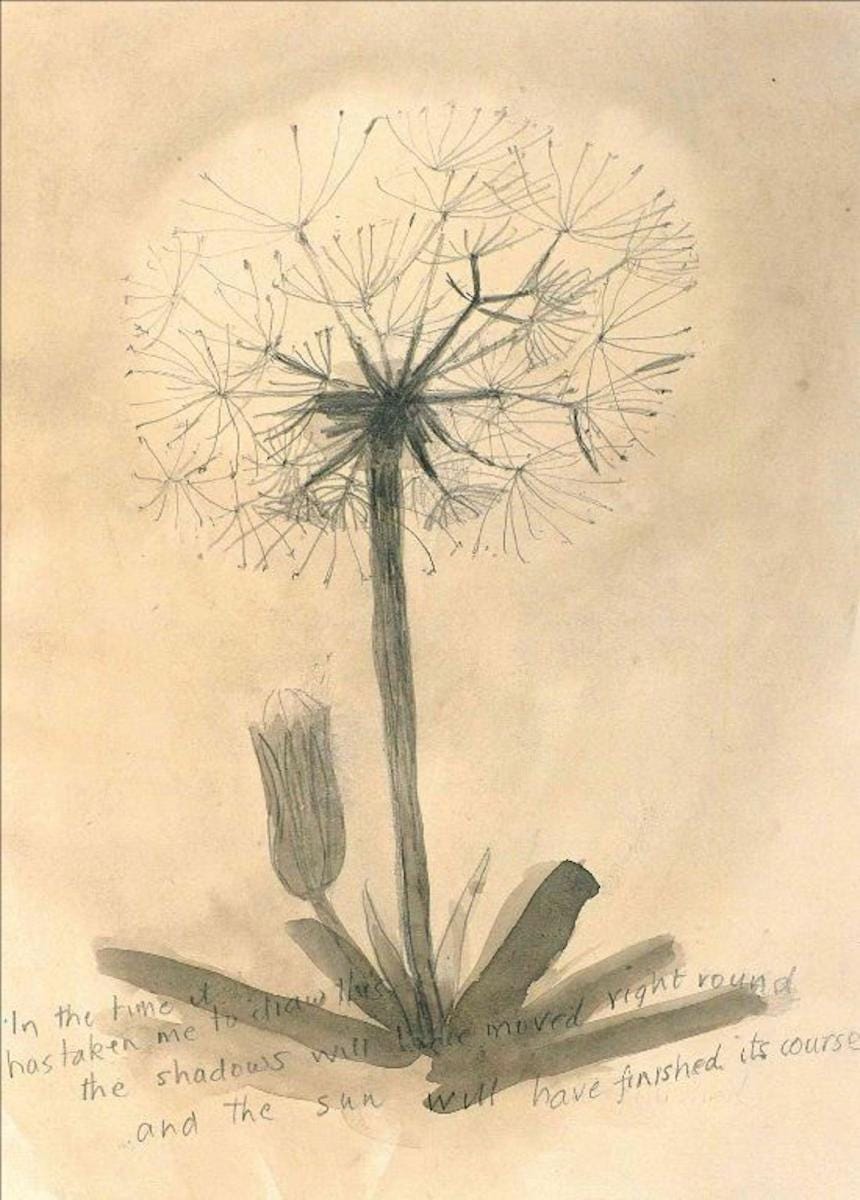

In the time it has taken…Watercolour and pencil 31.1 x 22.9cm Private Collection

I can think of no other painter that brings me such joy when I look at her work. She invites us to be curious about the natural world, note the rhythms of the countryside and elevate the commonplace. While she records her experiences, they are about her response to the world, and not cool observation alone. She didn’t drive, she walked or bicycled, or travelled by bus or train, gazing through the windows as she to travelled slowly, always noting moments that made her curious or gave her delight. Her titles too show wit and lightness, they are poetic haikus that reveal the joy of existence.

The Norfolk and Suffolk of the 1950’s and 60’s are fast disappearing - hedgerows have been ripped out to create prairie like fields, sprawling housing increasingly encroaches upon the ragged areas and now pylons are to stride across the landscape. I wonder what she would have made of these changes? ChristopherAndreae said when he first visited her , “she made it clear that our century was not much to her liking” and “how revolutionary processes occur faster and faster…A layman cannot hope to keep pace with them. I prefer the painfully slow”. In her work she has preserved something of an East Anglia that is changing rapidly, is under new and pressing landscape management. But, let us not dwell on that, but instead be grateful for her unique and delightful vision.

Below are some of my favourites.

Time still passes but it passes more slowly here. Mary Newcomb

The Lady with a Bunch of Sweet Williams, 1988, Oil on board, 54.5cm x 54.5cm Private Collection

Working drawing of the painting above. Pencil on wash on paper, 11.1 x 10.9cm

Insects on Hogweed, with the artist’s pencilled notes, describing their colours ‘Payne’s Grey thorax’ and how the ‘shell reflects the sky’ , 27.9 x 38.1cm

1st February: One more inadequate pencil drawing then I shall put down the pencils and turn to oils.

A Flock of Goldfinches Dispersing, 1993-1995, Oil on Canvas, 101.5 x 76 cms Private Collection

A charm of goldfinches whooshing upwards snatching the seedheads of the thistles at dusk. of this painting she said, “I wanted to say… how birds appear fragile in structure, yet strong, and fly with powerful upthrusts and twists, pushing out enormous bursts of energy”. This painting was lost in a fire in Andras Kalman’s flat and features on the cover of Ronald Blythe’s “Borderland”.

20th June In the end I think it is the goldfinches who have played the greatesr part - and the sun- the sun and the goldfinches.

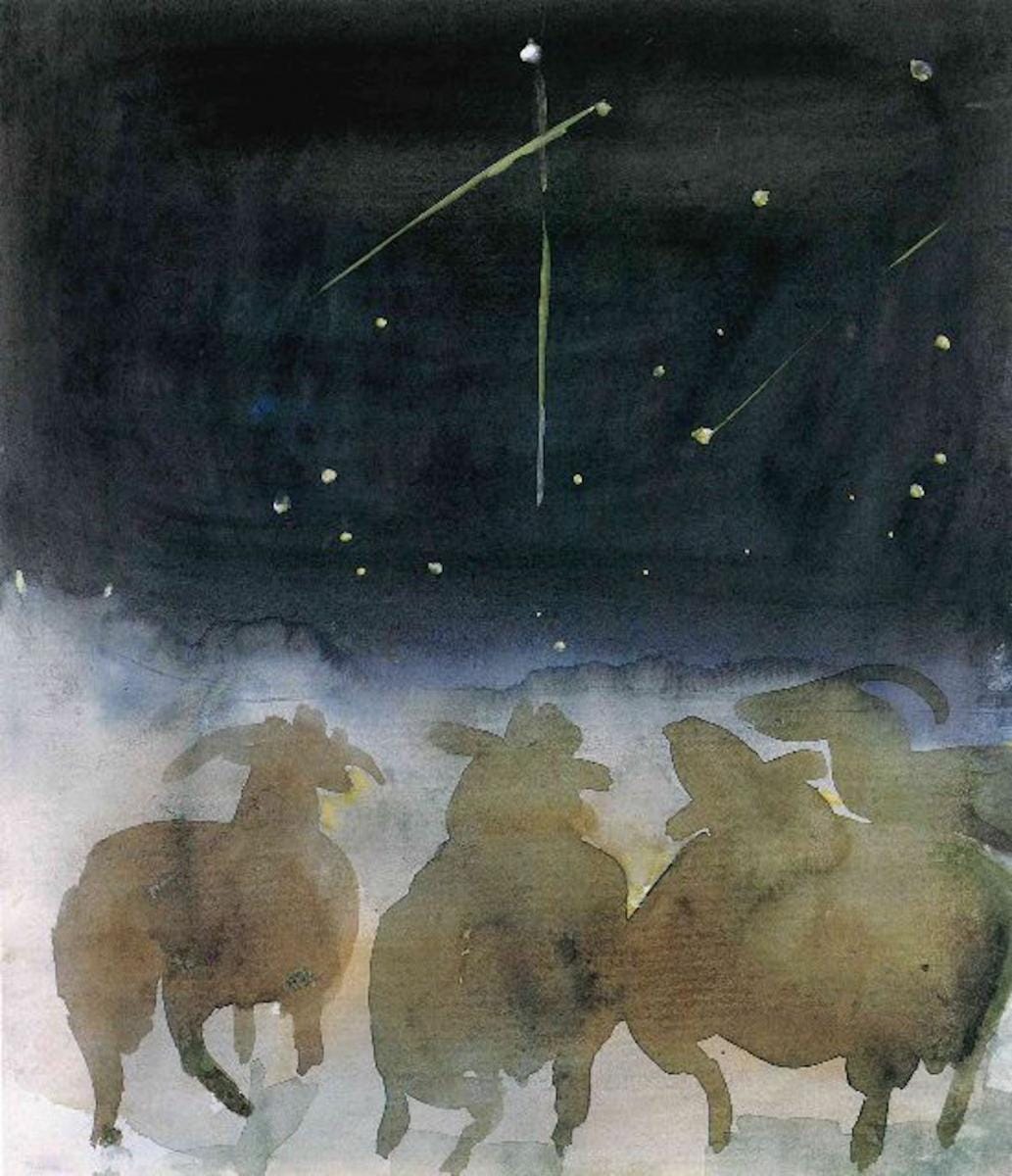

Ewes watching shooting stars, watercolour, date unknown, Private Collection I love how she conveys a sense of a collective moment as they gaze in awe at the night sky.

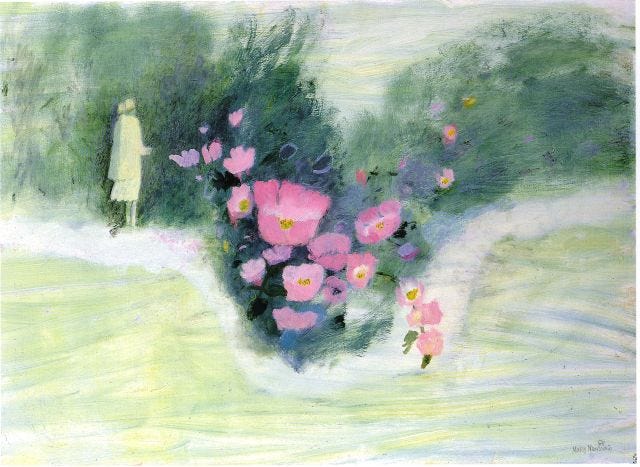

Wild Flowers will Soften the Stiffest Lady, 1988, Oil on board, 86.5cm x 64.5cm Private Collection

From her diary:

2nd June: dog roses…one individual one close up is a dramatic arrangement of pink…a bank is like a fabric or in detail like the background flowers of a mediaeval enclosed garden ref Kenneth Clark “Landscape in Art”or the details of a subdued French tapestry.

11 July: A new painting…It will be difficult to do, but I will try…On the common a lady walks stiffly along in her best suit and hat. The sky is mediaeval blue. The clouds are white. The lady stops and takes off her jacket and reveals a soft yellow blouse. She stoops to smell flowers that have no scent and goes on her way – her stiffness gone.

Flowers for the churchyard, 1989, Oil on canvas, 74.29 x 91.44 cms Private Collection

I love the colour palette of this painting: khaki green, mulberry, a flesh pink church and patches of Naples yellow. The image is so economic in detail and yet we know from the colours that dusk is falling and that the fading sun is shining through the church windows. She even describes some knapped flint on the wall.

Something to watch

In 2020 the broadcaster, writer and musician Clemency Burton-Hill suffered a catastrophic brain haemorrhage at the age of 38. My Brain: After the Rupture is not easy viewing, but her courage and sheer bloody mindness in the face of what has been taken away from her, and her determination to regain it, makes it important, and ultimately uplifting, viewing. In the programme she recites part of the poem “Chemotherapy” by Julia Darling, which is included in the brilliant series of Poetry Pharmacy books and thought I would share here:

Chemotherapy

I did not imagine being bald

at forty four. I didn’t have a plan.

Perhaps a scar or two from growing old,

hot flushes. I’d sit fluttering a fan.

But I am bald, and hardly ever walk

by day, I’m the invalid of these rooms,

stirring soups, awake in the half dark,

not answering the phone when it rings.

I never thought that life could get this small,

that I would care so much about a cup,

the taste of tea, the texture of a shawl,

and whether or not I should get up.

I’m not unhappy. I have learnt to drift

and sip. The smallest things are gifts.

I am so grateful to have been introduced to this film by

in her post Perfect Days and the Beauty of Sunlight Through Trees. This is a film of small illuminated moments that is so joyful that I felt I had been given a small gift. The final sequence, in such a beautifully nuanced performance by Koji Yakusho, was like watching clouds pass across the sun.Something to listen to

The Jura Affair I loved this literary thriller based on a story by William Boyd. Bethany Mellmoth, a George Orwell obsessive, picks up a copy of “1984” that has been dropped on the Tube. It turns out to be a rare, signed first edition and she decides to return it to its owner on Jura. And so the adventure begins…great fun!

Something to read

Before I leave you can I recommend two Substacks? Firstly, Bimblings by the writer

, whose forthcoming book “Letters from Wonderland” I am so looking forward to reading, and whose writing reminds us to notice and observe in a world that is “in need of some magic”.And I very glad that

has created A Year of Quiet, by collating a year’s posts and in so doing has created a beautiful thing.Thank you for joining me here and I hope you found something that brings you cheer. Do drop me a line, as I always love to read your comments, and don’t forget to press the heart if you like this post as it really helps spread the word.

I shall be back in a couple of weeks and look forward to your company again.

Further reading

Mary Newcomb - Christopher Andreae (This can be accessed through the Internet Archive. Thank you very much to

for alerting me to this. Here you can find many more examples of her paintings that I would have loved to included here, but was unable to locate them.)Borderland: Continuity and Change in the Countryside - Ronald Blythe

Meetings with John Clare - Ronald Blythe

Talking to the Neighbours: Conversations from a Country Parish - Ronald Blythe (Each with illustrations by Mary Newcomb)

A Broad Canvas - Ian Collins

Water Marks - Ian Collins

Wildwood: A Journey through Trees: Roger Deakin

Mary Newcomb: Drawing from Observation - Tessa Newcomb and William Packer

Billingford Mill, 1975, Oil on canvas, 70.5 x 61cm Private Collection

This mill has recently been renovated and is just a couple of miles from where I live. Now a very small village, it has been earmarked to become of the “new” towns.

from “Mary Newcomb,” Christopher Andreae

from “Water Marks”, Ian Collins

from “Wildwood”, Roger Deakin

By the way, clicking around online I see that there is an exhibition of Mary Newcomb's drawings and paintings at the Crane Kalman Gallery in Knightsbridge right now, until May 5th!! There's a record of what they're showing in the catalogue, also online.

I loved this, am new to Mary Newcomb and now want to find out more about her. Thank you for introducing me to this new lovely thing.